When I became a reporter, on this day in 1960, the great ocean liners still sailed regularly to Europe and North America, and was it possible to take a ship between most of the capital cities.

But not for much longer.

Some afternoons, when Sydney and Mary and Susanna, Malcolm, Jean, baby Fiona and I then lived in working class Clovelly, there would be three jets in a row after school, a Qantas 707-138, a longer fuselage Pan American 707, and a BOAC Comet IV.

The arrival of the jet age was as much a visible, and insistent signal of change as television and satellites.

The jets were a homework disrupting event. We’d rush outside to watch. Just as the ear splitting noise of a Super Constellation grinding its way into the air was an event that would unpack a practice scrum, or completely silence a classroom.

And then, one day after the Leaving Certificate exams, it was time to go to work, to Broadway with a letter from the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, Bill Fitter, advising me to turn up at 2 pm in the teleprinter room, next to the sub editors room, on the fifth floor.

My job was that of a copy boy. But to lift my pay above around £5/11/6d to more than £6 required taking the Saturday police rounds radio monitoring shift for the Sun-Herald, and, since I wore a suit, and looked like a young reporter, I wrote stories. Little stories. Filler stories. No-one noticed.

Until one Saturday night. The inmates at the Parramatta Girls’ Home set fire to the roof and threw burning mattresses onto the police below, and the usual police roundsman being otherwise engaged, I had called up a photographer and a radio car, and written a big story, for page one with a spill on page three. This was noticed by ‘Granny’.

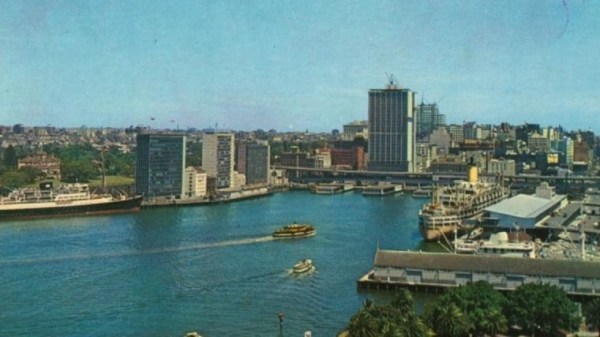

How this quickly lead to being paid as a cadet reporter, rather than fired is for another time. I soon became the shipping cadet, and by historical accident, the Sydney Morning Herald’s last full time shipping cadet, as the jets brought the age of the great ocean passenger liners into deep decline , with fewer celebrities to be interviewed as their ships (which you joined off the customs launch from 7 Circular Quay) made their leisurely way to Walsh Bay or Woolloomooloo.

Having lived on Goat Island in Sydney Harbour for part of small boyhood, (in the cottage furthest from the Harbour Master’s mansion), when my father a marine engineer decided to take a land based position with the Maritime Services Board, and having being taken to sea with him at other times, shipping had become a part of my daily life.

This was a Sydney that read the shipping column with as much attention as it read Column 8, (which I also later edited for about a year), a city in which the deep sound of an ocean liner’s horn and its attendant tugs carried right through the offices and warehouses and quite far into the suburbs.

It was the end of a time when bands played wharf side, and streamers stretched and snapped and tears flowed, as parents waved off their children sailing for Southampton or Genoa.

(That’s what the A380 needs today. Brass bands and streamers. Bring back a bit of ceremony and romance to long distance travel. )

But it was also a city at the start of amazing changes, some of them good. Planes fascinated kids back then. Sometime before the war ended I saw a yellow Tiger Moth flying over Springwood where I was born, the first plane I remember seeing. Right down to being able to see a pilot in the open cockpit.

By the time I left home, I had flown in DC-3s, past rather than over the Snowy Mountains, in DC-4 Skymasters, and something very rare, an Airspeed ‘Elizabethan’ as Butler Air Transport called them. These second hand ‘Elizabethans’ had some facing seats railway carriage style, and big oblong windows, all the better through which to see the countryside not far below, in a machine that seemed to climb just fast enough the clear the Blue Mountains by the time it reached them.

Before then, a Comet III did a tour that included Sydney, in December 1955. We were a large tribe, and living in Clovelly by then, and decided to walk to Kingsford Smith Airport to see it come in. With Pippy, our toy foxie. By the time we reached Maroubra, minus Pippy, who wisely turned back and caused parental alarm by arriving home alone, we sidetracked ourselves by trudging up and rolling down the sides of the large sand dunes that once were there, near a now vanished Speedway, when suddenly the sleek jet made a surprise banking turn almost beside us on its way to the runway. We could see the dolphin shaped nose, the oval windows, and the golden Speedbird on the tail. We had seen the shape of things to come, and went home happy, to a ‘where the hell have you been’ welcome.

Less than a year later another astonishing ‘shape’ roared low over the ‘battler’ part of the eastern suburbs, a delta winged Avro Vulcan B1, which was to crash at Heathrow Airport a few days later at the end of its around-the-world tour.

In the same time frame, there was a visit by a USAF Convair B-36, an incredibly complicated bomber which had six rear facing propeller engines and two sets of two small turbo-jets.

And sometime in 1955 the original Boeing 707 ‘precursor’ the Dash-80, flew over Clovelly Primary School. We didn’t know it was coming either. Something I had seen in Popular Mechanics or Life magazine materialised over the ‘queue’ for the tiny bottles of milk that were distributed at play time. A flying saucer couldn’t have caused more astonishment, including among the teachers.

Fast forwarding to the present, it is easy to conclude that the thrill and pleasures of flying have been lost. The fantastical, often impracticable aeronautical design adventures of the post war era have been replaced by the theme and variations of pressurised tubes with seating that becomes the less comfortable as it becomes more affordable.

Since US airline deregulation in 1979, and the privatisation of the British Airways soon after and the end of the two airline domestic carrier policy in Australia in 1989, the stories about airlines have been more about economic and competition reform.

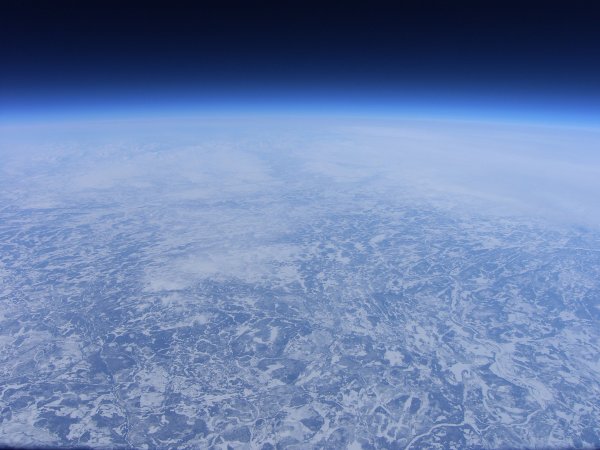

More recently, it has become apparent that the air travel markets, even in Australia, are not ‘mature’. As fares fall, and as we become richer, air travel in this country is predicted to treble by 2030, although the size of this activity will by then be approaching the thresholds of viable high speed rail developments, and sub orbital space transportation between continents will be high above the horizon, in the logical succession to the 21st century version of the joy flight, a rocket ride.

In the 60s the mainstream wisdom was that the 16 daily Lockheed Electras or DC-6Bs that Ansett-ANA and TAA flew in tandem, almost to the minute, between Sydney and Melbourne, were all that Australia would ever need.

In 1970 or early 1971 Ross Alexander, Reg Ansett’s minder summonsed myself to a smoke filled room at the top of Swanston Street where RM lectured the ABC television news audience , in black and white, about how nothing larger than a Boeing 727 could ever be justified in this country. I had suggested otherwise on an ABC program, and a rare TV interview was considered necessary to curb the heresy.

Ansett had immense power over the timing of change in Australian aviation. Australians were forbidden interstate jet travel on Ansett-ANA and TAA until it suited Reg Ansett in the mid-60s but you could catch a BOAC Comet IV to Darwin, from Essendon of all places, or an Air-India 707 to Perth in the early 60s for a 25% surcharge on the regulated domestic fare.

The 80s however changed the story emphasis in air transport in Australia to the inevitability of deregulation, privatisation and the consequent enabling of increased social and business mobility. James Strong saw this with sharp, and convincing clarity, and the early 90s consolidation and privatisation of Australian (formerly TAA) and Qantas was an overt agenda from the end of the previous decade. Bryan Grey saw the opportunities throughout the 80s, contorted however by the two airline policy limitations that once repealed lead to his unsuccessful but heroic foray with Compass.

I plan to publish an account of those times in a book, although its main emphasis will be on the low cost revolution that Brett Godfrey, with ‘small change’ from Richard Branson, was able to achieve with Virgin Blue, as well as the consequences intended and unintended that arose from that success. There is much to tell about these and related events, leading up to the present, and how essential the enabling of less expensive travel has been to improving people’s lives.

We’ve now arrived at a time and place of considerable peril for consumers. Airline managements have largely abandoned the legacy investments in flight standards and pilot experience, even as piloting itself continues to change from the skills required in the 707 and DC-8 age to those of systems management.

The dominant view is that Australia can’t afford exceptional excellence in aviation. We have to dumb down to ‘world’s best practice’ which is a euphemism for ‘legal or regulatory minimums’. Managements seem to want pilots to think like shareholders or accountants, rather than pilots. Regulators are quick to make excuses for carrier failings rather than carry out their obligations to the public. The weasel words, ‘working with’ industry stakeholders is short hand for inaction.

Difficult but essential issues about the public administration of air transport are beginning to tower over the landscape, like a deadly storm line. These issues are with us now, when the media itself is imploding, and the investment in or will to pursue their coverage is minimal.

The lucky country will not enjoy lucky skies for ever. The luck has to be earned.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.