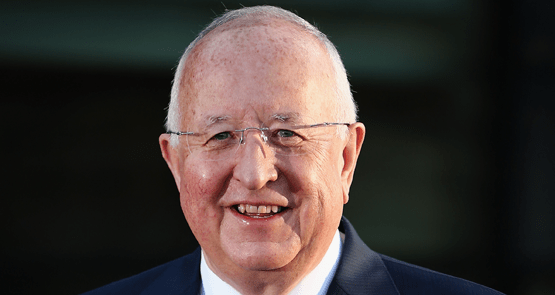

“Dividends are very high on our radar screen. Personally for me they are very, very important. We have shareholders who have invested in our business. They put their faith in us and I believe they need a fair return,” Rio Tinto executive Sam Walsh told Bloomberg last December.

Two months later, Rio announced it would cut its so-called progressive dividend due to the sheer scale of the commodities slump, led by iron ore, the world’s biggest bulk-shipped resource apart from oil. And now Walsh is gone, announcing yesterday he would step down.

“We are taking to revise our dividend policy, this is a long-term step …” Walsh said. Complete backflip. The former car salesman from Western Australia appears to be the highest-profile casualty of the ongoing commodities bust so far after being replaced as chief executive — retiring, you see — after only three years in the job. (Anyone who thinks iron ore bottomed out at US$39 per tonne needs to check their supply-and-demand spreadsheets). The sharemarket cheered, sending Rio shares up 2.44%.

Walsh said, at the time that he did the reverse ferret on dividends, that the company believed there would be more distressed players — not just the junior and mid levels of the market, but also the bigger players. That has been clear from the stress that both Glencore and Anglo American — top five miners both — have come under on the London sharemarket.

Yet Walsh was brought in to replace the big-spending Tom Albanese to right the company’s balance sheet and ruthlessly slash costs, which he has done, making Rio the industry’s lowest-cost supplier, and then proceeding to ramp up supply in a market already oversupplied.

The intention is clear. In implicit tandem (no one is suggesting any collusion here, just common interest and strategy) with its former oligopoly partners BHP Billiton and Brazil’s Vale SA, Rio wants to run the small and medium iron ore miners — and that includes Anglo and Fortescue Metals Group — out of business.

Unfortunately for shareholders, such a strategy, which lowers margins and reduces cash flow as prices are driven down further, cannot operate in tandem with increased, or even continuing, dividends.

Pretty much all Australians are beholden to the strategies of the big miners, because they make up big licks of all our superannuation funds. Walsh, with his millions, has no such worries.

But hidden away under Walsh’s aggressive cost-cutting is the fact that Rio’s targets for China’s steel-making sector were way, way off. As Crikey has noted more than once, Walsh has steadfastly been behind Rio’s insistence that China’s steel production would climb to 1.1 billion tonnes, justifying its “pump and dump” strategy. But even China’s notoriously bullish government is now saying that the maximum is 800 million tonnes.

With 1.5 tonnes of iron ore required to make 1 tonne of steel, that’s about 450 million tonnes of iron ore out — or more than Rio’s entire production. Walsh’s entire career at Rio has been in iron ore; it’s now over, and so is he.

So it’s also apposite that Walsh should decide to skip off from the company, his saddlebags packed with countless millions of dollars in pay and bonuses, as labour unrest continues to build in China, the mining giant’s main market.

China’s workers have good reason to be anxious: its government has been outlining plans to cut millions of jobs in state-owned enterprises, and one of the key sectors where the pain will be felt is the steel industry, which is by far Rio Tinto’s single largest customer.

Once again, China Inc. has vowed to strip back excess capacity from a steel industry that some estimates say is capable of producing over 1 billion tonnes of steel each year. The problem is that the 800 million or so tonnes it is currently making is far more that the country’s economy — in the middle of a sharper-than-expected cyclical slowdown, coupled with a secular, once-in-a-generation restructure — needs.

It’s not the first time Walsh has gotten it wrong on China: he was the executive in charge of the iron ore division who made the decision to leave the locals in charge in the mid-1990s under chief salesman Stern Hu.

That decision embroiled Rio in a bribery and industrial espionage scandal. Hu and his colleagues remain rotting in Chinese jails. Walsh got bumped up to the board and, a few years later, to chief executive.

Rio’s share price hit $70.15 a month after Walsh stepped in as CEO; yesterday it closed at $43.73.

So Walsh “retires” from the company much as he found it: at something of a crossroads. Sound familiar? In the mining sector plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose (the more things change, the more they stay the same).

An alternative speech for Walsh: “Dividends are very high on our radar screen. Personally for me they are very, very important, because they determine my performance bonus. We have shareholders who have decided to take a gamble on our business. They have been handsomely rewarded in earlier years when we got lucky during the resources boom, and now that the cycle has turned, it’s time for them to take a bath”.