Sorry Australia. That stable government that you wanted? That government that would just get on with running the country rather than obsessing about its leadership? That political system that we had before 2009, when parties were elected and governed and then went to the polls three years later with the same leader?

Not happening.

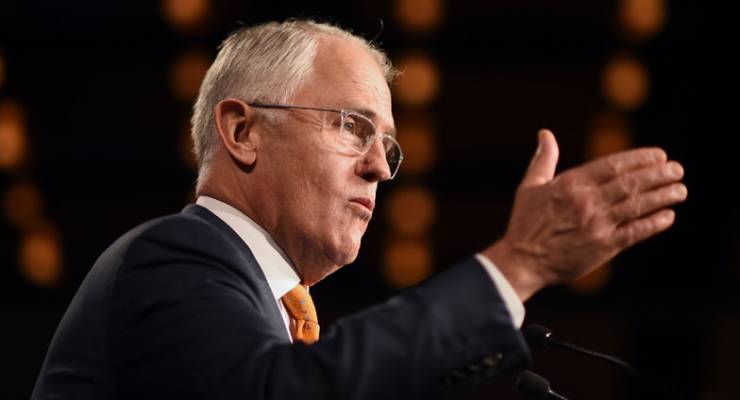

If anything, we’re about to enter an even more turbulent political era, because Malcolm Turnbull’s double dissolution gamble has failed to pay off. Indeed, it now looks like one of the most costly political mistakes of recent political history. If Turnbull is able to form a majority government — and that’s still in doubt — he faces a resurgent and angry right within his own ranks that can now argue that the one thing Turnbull has ever offered the Liberal Party — electoral popularity — has turned out to be mirage the moment it was subject to a real test. Already outriders of the far right like Andrew Bolt are attacking Turnbull, while Abbott loyalists like Peta Credlin have openly criticised his double dissolution strategy (which, let us not forget, was regarded as a brilliant move by much of the press gallery when Turnbull unveiled it in March).

All of this is on Turnbull. There was no need for a double dissolution election — indeed, it now looks unlikely that the trigger for that, the Australian Building and Construction Commission bill, will pass in a joint sitting. But Turnbull impatiently rushed to a double dissolution, heedless of the risks, and now has his government dangling by a thread. It’s now very hard to see how Turnbull will survive until the next election, with the right gunning for him and his party badly split over the issue of same-sex marriage, on which Turnbull has promised a plebiscite by the end of the year (assuming he can get a bill passed for one, which now seems very uncertain).

[Abbott’s same-sex marriage plebiscite might not happen after all]

The other big loser from last night is Turnbull’s partner in Senate voting reform, the Greens. On current counting it seems the Greens have failed to secure a second lower house seat — they’ve come close in Batman (which may yet fall to them,) but faded after a strong start in Wills. But the Greens’ strength is in the Senate, and on current counting they will lose at least one, probably two and perhaps three Senate spots from South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania, respectively. Moreover, the NSW Greens were hammered by Anthony Albanese in Grayndler. The party had poured nearly all of its state resources into that seat and Richard Di Natale was virtually camped there in the early days of the campaign, but Albanese fought back hard and secured a swing of over 11%, completely trouncing his Trotskyite opponent — a remarkable outcome for a seat the Greens were convinced they would win.

[All aboard the ghost train for Labor’s Mediscare campaign]

Where did the campaign go wrong for the Coalition? Many Liberals were saying last night that the failure to run a strong negative campaign against Labor was what cost them. Turnbull and Tony Nutt, who ran his campaign, were determined to be positive and only periodically ramped up attacks on asylum seekers throughout. And the campaign against Labor’s negative gearing proposals was a failure — but that failure belongs to Treasurer Scott Morrison, who had a woeful campaign and was in hiding for most of it.

Turnbull himself blamed the outcome on Labor’s Medicare scare campaign — indeed, he bizarrely devoted much of his extraordinarily rancorous election night “victory” speech (delivered early this morning) to railing at Labor and threatening to call the police about the Medicare campaign. It was perhaps the most remarkable election night speech Australians have witnessed from a major party leader, particularly when Turnbull felt obliged to attack critics from his own side (that’s you, Peta Credlin) about his double dissolution strategy. It seemed “old Malcolm” had returned — not the leather-jacketed moderate of the Abbott era but the angry, dismissive Malcolm of his first leadership stint in 2008-09.

Turnbull was also, simply, out-campaigned by Bill Shorten, who proved far more effective and disciplined a campaigner than the Coalition expected — indeed, Shorten has consistently surprised his opponents (both within his own party and in the Coalition) by his resilience, work ethic and willingness to take policy gambles. Shorten has seen off one Liberal prime minister and has come close to seeing off a second in less than a year — an achievement reminiscent of the modern gold standard of opposition leaders, Tony Abbott.

So for now, we wait until the smoke clears and we see what sort of a majority Turnbull is able to command — if he able to do so at all. But the stable government that he campaigned for so hard in the last week is further out of reach than ever — especially for voters who are sick of political theatrics and just want governments to get on with governing. We’re back to 2010: a government barely able to command a majority and a prime minister targeted by relentless forces within their own ranks gunning for revenge.

Bernard, I reckon a better headline would have been “MALCOLM TURNBULL CRASHES TO VICTORY”

Arrogant Turnbull should be for the high jump. Misjudged electorate on Superannuation, Big Business Tax Cuts, Knifing a PM and underestimated Unions, Getup and Labor coordinated campaign

The increasing “anything but the majors”, combined with the fall for the coalition suggests that the Australian people prefer accountability over stability.

With the senate reform, I exercised the option to leave the majors off my senate ticket.

Likewise, I refused to place a vote for either major party in the senate.

When has our political system ever been ‘stable’? The most stable aspect of Australian government is its anticipatorily rapidly increasing farcicality..

The federal government was pretty stable 2004-2007 and gave us such joys as SerfChoices, Nauru mkI ad nauseam.

I think the electorate is disillusioned not only with the majors but also with journalists and commentators who relentlessly pushed the view that the coalition had it won. My feeling has always been that the NBN – or at least the absence in regional areas of a broadband that could be described as first world – was a huge issue. The other issue largely ignored was climate change. I live in Lyons, and farmers in this electorate were devastated by the damage caused by recent floods. They know that the climate is changing as they see the proof every day. They also know that the coalition has no plan to deal with it.

Stable government, innovation, jobs and growth plan. Mal has been drinking tea infused with mushrooms. He resembles a top hat wearing character in Alice in Wonderland.

Mr Turnbull, your sh*t sandwich is served.

But that’s the eternal problem – it depends how much bread one has.

And Talcum has lots – even if it is farrrr away in the Caymans.

D’ya reckon he’s been checking house prices there?