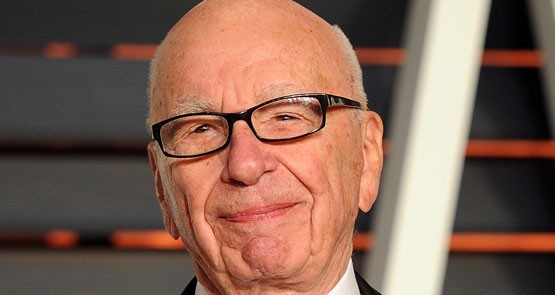

Rupert Murdoch cheats at tennis.

To quote long-serving editor-in-chief of The Australian Chris Mitchell, who spent decades in positions that allowed him to socialise with Murdoch, the media mogul’s serve is, well, unconventional. Mitchell writes in his memoir, released this morning:

“The boss insisted that two serves were not enough for him, and we had to put up with letting him keep serving until he got a ball in. He certainly surprised me because his serves, although initially long, had a lot of weight in them and were at that time stronger than my fifteen-year-old son’s were. The game was hard, and at one point, with Rupert guarding the net, I unleashed a backhand and he copped it right in the chest. We all held our breaths, and [former News Corp CEO John Hartigan] came running down from the house. But Rupert just laughed and played on. He was desperately keen to beat his oldest boy and that Queensland fellow. And beat us he did.”

The anecdote is used to illustrate Murdoch’s eternal competitiveness; Mitchell doesn’t mean to stick the boot in. He writes, in the prologue, that he hopes his “reflections on the Murdoch family and News Corporation will being some much-needed balance to an often hysterical discussion about this media empire”.

Mitchell’s chapter on his relationship with Murdoch is rather lengthy, even though, he says at the start, he would never suggest he and the most powerful Australian in history were particularly close. “It really is not possible to be an Australian-based editor and be close to a man who lives on the other side of the world and runs hundreds of newspapers, television stations, cable networks, movie companies and book publishing businesses,” the editor writes.

Still, the Murdochs are written as having an outsized role in the lives of their most senior employees. Mitchell’s book is full of stories of his cutting holidays short after a call from one of the Murdochs, keen for a last-minute chat on some topic or other. On the night of the 1995 Queensland election, during which Mitchell was editing The Courier-Mail, he was called away to a Murdoch family dinner, at which the family was also entertaining a bunch of rugby players. Mitchell spent the dinner discreetly checking the ABC’s election coverage, and after dinner, he got an insight into his boss’ character. “Rupert is a committed, fearless gambler,” Mitchell writes. When the mogul’s wife Anne and daughter Elisabeth suggested taking $2000 to the casino later in the night, Rupert scoffed at them. For gambling to be fun, he said, it had to hurt if you lose. He told a tale of miners he had watched as a young man in Broken Hill who’d risk a week’s pay at the pub. “That’s gambling. When you risk everything and could lose your family’s food for the week,” Mitchell recalls him saying. He goes on:

“At that moment I knew he was a much bigger, more committed punter than any of the Packers. They would bet small percentages of their total wealth … But this man so excited at this moment was capable of betting his whole company.”

Mitchell had first met Murdoch in 1982 while a subeditor at the Daily Telegraph. He’d been working on a business story when someone behind him began reading over his shoulder. “Don’t call the company Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation,” the person said. Turning around, Mitchell realised it was Rupert, who, smiling, told him it was a publicly listed company and walked off.

It would be the first of many encounters. While Mitchell has been criticised, including by Tony Abbott and his successor at The Courier-Mail David Fagan, for breaking confidences in the book, it’s hard to see Rupert Murdoch being too unhappy with his portrayal. Time and time again, Mitchell describes Murdoch’s generosity, sense of humour, eternal curiosity and willingness to let people try things, even if they fail. “I felt great admiration for him and the deft touch with which he had carried sixty years of publishing genius,” Mitchell writes after another encounter.

Though there is one story that could ruffle a few feathers. After Mitchell briefed Murdoch on an idea for The Australian, Murdoch mentioned to him that the people listening had probably all been nodding furiously when Mitchell outlined the plans to them earlier, but they were now watching Murdoch for cues. Rupert writes:

“Rupert wanted editors with their own ideas. But in the commercial side he was happy with yes-men because he knew he had a more complete understanding of the business than any of his managers did.”

Mitchell describes himself as having grown close to Lachlan Murdoch during his time in Queensland, but the presumptive successor to the empire might be less happy with his portrayal. During Abbott’s prime ministership, Lachlan Murdoch and Mitchell met with Tony Abbott to try to salvage the relationship after John Lyons’ bombshell feature on Abbott’s office. Rupert Murdoch encouraged Mitchell to “go tough on Abbott”. Mitchell muses that the mogul wished his son were “more muscular” in his dealings with politicians.

“Although this has nothing to do with me, and I have always been muscular enough myself, it is true that Lachlan, like his siblings, is unfailingly polite in formal situations. I see that as a strength. I wish more politicians had been as polite to me as I was to them over the years.”

During that dinner, Mitchell notes Abbott’s deep sadness at the fate of Myuran Sukumaran and Andrew Chan, members of the Bali Nine executed in Indonesia for drug offences last year. Lachlan Murdoch took a different view.

“Lachlan argued against Tony’s compassion, saying that Chan and Sukumaran deserved exactly what they were about to get. As with his views on gun control in the United States, Lachlan’s conservatism is more vigorous than that of any Australian politician, Abbott included, and usually to the right of his father’s views.”

Later, Mitchell gives two reasons for the sudden 2011 departure of longstanding CEO John Hartigan from News Corp (he was replaced by Kim Williams). The first was the scale of the digital challenge confronting the company. The second was more political:

“Let’s face it, we all knew the other reason Harto had finally bitten the dust. He had failed years earlier to welcome Lachlan Murdoch back to Sydney with open arms after Rupert’s oldest son returned after his resignation from the company in 2005 after having tangled with an older, tougher opponent in Fox News CEO Roger Ailes. Lachlan had thought, after quitting his international role based in the United States, that he could simply return to Australia as a local pooh-bah, but Harto had little option other than to close the door on his former close friend, given Rupert’s position at the time that Lachlan had left the company.”

Lachlan Murdoch’s conservatism is in stark contrast to how Mitchell describes James Murdoch, who had led the company’s British papers towards a zero-emissions target. Lachlan Murdoch, on the other hand, is described as “almost cheering” at a company event when Andrew Bolt and Al Gore had a fiery exchange about climate change.

Murdoch serving as many times as it took to get a tennis ball in the service court is not an illustration of competitiveness.

It’s a perfect example of breaking the rules, disrespecting the game & ignoring conventions towards all opponents. Exactly how he runs his publishing empire.

If Murdoch was genuinely competitive he’d insist on a level playing field but, instead, he demands an advantage. Personally, I couldn’t enjoy a rigged game.

“Personally, I couldn’t enjoy a rigged game”. Zut, I enjoyed the dryness of that barb – you are the Noel Coward of the comments section. I see you in tennis whites, thrashing Rupert, but not one drop of sweat on your brow. “Sorry Rupert old chap, you can’t have another shot as it’s old school rules here. Cucumber sandwich?”

‘but they were now watching Murdoch for cues.’ Exactly my experience of a brief period when pitching a big idea to senior execs at The Australian. I got the distinct impression that they were nervously (and metaphoriclly) looking over their shoulders to see what Rupert would think.

Could someone remind me whether to describe a person as a lickspittle is considered impolite?

Not that I give a flying, this man has the ethics of a boiled radish.

“Lachlan Murdoch’s conservatism is in stark contrast to how Mitchell describes James Murdoch …”

Myriam, I feel like there are a few paragraphs missing, and you have left us hanging. I wanted to know what is different about James. Is he less honourable, less conservative? Given his “mistruths” to the British parliamentary inquiry re the phone-hacking scandal, I would wager that he is deficient in the “honourability” stakes.

Hi Angela. Mitchell writes that James Murdoch is less conservative – certainly more of a greenie at least.

A right-flummer knight’s dream – Mitchell’s Titania to Rupert’s Bottom?