Malcolm Turnbull’s week, which started in awful fashion but improved by dint of his showing some mongrel on Wednesday, improved considerably last night when Reserve Bank governor Phil Lowe — with the careful phrasing of a central banker — backed his case for company tax cuts.

Lowe, as part of a concerted drive to put the Bank’s stamp on economic policy leadership at the start of 2017, gave a speech last night that offered a broad look at the economy, and made this point:

“we need to make sure that our tax system is internationally competitive. One example of this complication is in the area of corporate tax, where there is a form of international tax competition going on in an effort to attract foreign investment. Like other countries, we face the challenge of responding to this, while achieving a balance between recurrent spending and fiscal revenue.”

Undoubtedly Lowe was aware of how his endorsement of the government’s case would be seen. It represents a significant intervention in a current political debate — albeit one well within the bounds of propriety. You can be sure the government will point to it as it continues to make its case for tax cuts for the world’s biggest companies.

What Lowe didn’t address, however, is exactly how to reconcile “responding to the challenge” of tax competition with the other priorities identified in his speech. Lowe explained the need for “ensuring that our public finances are on the right track … by rebuilding our fiscal buffers”. Fair enough, no one will quibble with that. But Lowe also believes — continuing a theme that the RBA under his predecessor Glenn Stevens repeatedly discussed — that we have to invest in infrastructure

“… our population is growing strongly which is a source of dynamism for our economy. But this growth can put strains on our infrastructure, including on transport infrastructure. These strains can reduce public support for a growing population. They can also impair our ability to compete and to be as productive as we can be … Investment in transportation infrastructure can also play an important role in addressing housing affordability, which is an increasingly important issue.”

But how to pay for it?

“The positive news here is that there is no shortage of finance for the right projects. The task we face then is to identify the best possible projects, harness the planning capacity of government, design the best deal structures to attract private finance where it makes sense to do so, make sure that the construction process is as efficient as possible and price use appropriately.”

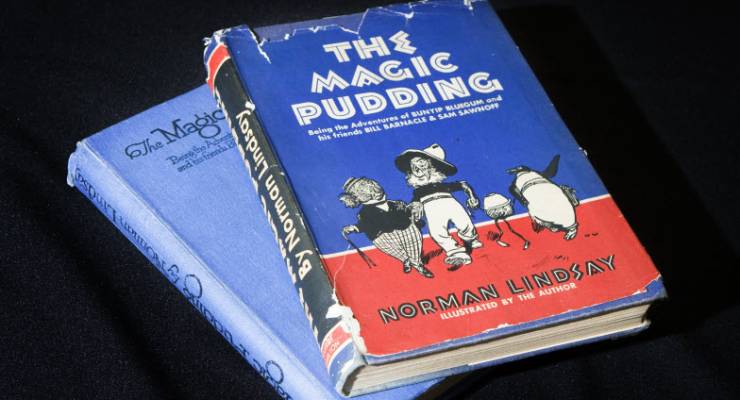

That’s actually a little glib from the RBA governor. Australia now has a near-thirty year history of trying to develop effective models for attracting private finance to infrastructure projects, with a success that could charitably be described as “mixed”. No matter how cleverly a deal is packaged, projects will need investment from government — although under the current government, public infrastructure spending has fallen markedly (and is way below the levels repeatedly claimed by the government). Where does the money come from while we’re rebuilding our fiscal buffers and cutting taxes so that we can play in the global game of beggar-thy-neighbour on corporate tax? Which magic fiscal pudding will enable this?

Lowe might also have mentioned that when it comes to infrastructure investment, industry superannuation funds are well ahead of other sectors in bringing private finance to projects — and left his listeners to note that despite that, industry super is still number one on the Coalition’s ideological hit list.

The business lobby, its media boosters and the government used to insist that company tax cuts can be done easily over 10 years, while providing an array of economic benefits — indeed, there was nothing that a company tax cut wouldn’t do — increase investment, increase productivity, increase wages, increase employment, increase growth, increase tax revenue. As we’ve repeatedly explained, none of these benefits have been demonstrated in countries that have cut corporate taxes. But we don’t hear so much about all those benefits any more — instead, the main argument is now that because Donald Trump is going to do cut company taxes, we have to as well. If you advanced that argument about protectionism, you’d be rightly attacked for advocating a return to the 1930s (even though that’s exactly what Australia and many other other countries have been doing on anti-dumping for some time).

But the $50 billion bill that comes with giving a huge tax cut to companies that already pay far below the 30% headline rate has to be paid for somehow. It’s a pity Lowe wasn’t willing to go further into the debate and identify which spending should be cut, or which other taxes should be increased, to pay that bill and rebuild our fiscal buffers while investing in infrastructure.

On the RBA’s official charter page

http://www.rba.gov.au/publications/annual-reports/rba/2015/our-charter-core-functions-and-values.html

The word does not appear once, ie zero, zip, nada – a.k.a. not there.

As per usual the world’s latest version of the highest paid central banker on Planet Earth has gone out and talked completely outside his remit.

Time to end the one way bromance – and seriously take the RBA leadership to task for the past 10 years of failed long term economic management.

What have we – 3 property bubbles, 3 currency bubbles, a mining investment boom that returns virtually no net income to Australia, and the list goes on and on. All of these relate to monetary and currency policy – both of which are clearly written as central to the RBA Charter.

The so called independent RBA experiment has been a monumental failure. It is nothing more than a convenience of government to outsource economic responsibility to the world’s highest paid central banker.

Other than defense what else is the federal government truly responsible for other than – the economy.

That’s annoying – the crikey comment engine does not allow you to include a word surrounded by greater/lesser than symbols for added emphasis

That second sentence should read …

The word TAX does not appear once, ie zero, zip, nada – a.k.a. not there.

Please – Crikey can you upgrade to the Disqus engine and solve these editing problems once and for all.

The governor should be sacked at once with an almighty smack over the ear. First he is commenting on something outside his duties, second he is clearly a fool if he thinks this works as it hasn’t anywhere else. Finally he has brought the competence of the RBA into doubt. If he had said that it was a stupid idea, he would be out the door, and rightly so, though at least he would have been telling the truth.

Hockey did say it had been politicised.

So, we lower our company taxes to match other countries, particularly the US.

So they lower them further. So we have to follow suit.

All the way down to 0 company tax.

I think there should be an amendment that requires companies claiming the lower tax rate to prove that they have employed more people because of the tax cut.

Since the rate cut is ~17%, companies claiming the lower rate should have to increase employment by ~17%.

Another LNP/IPA motor mouth stooge!

Just what we need right now!!