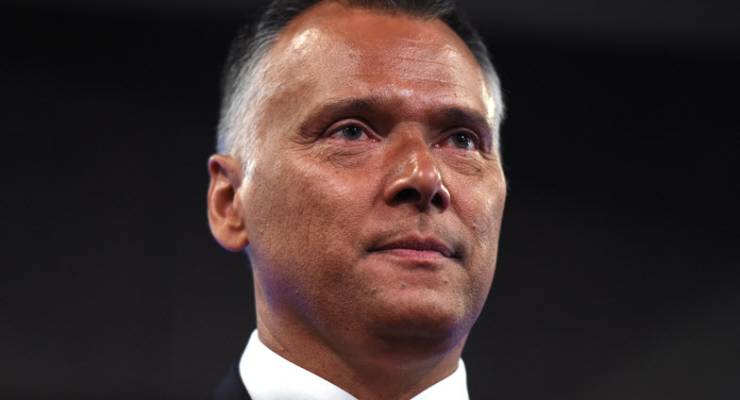

Stan Grant has done what journalists should do: bring a debate floating around just below the public gaze into the mainstream, positioning it in the context of long-term shifts in Australian society and attitudes.

Grant hasn’t so much discovered the issue, as he’s mapped it and shared it with the Australian community. The hardest story to write is one that reflects the flow shifting imperceptibly day to day, as opposed to discrete events, one after the other. The easiest story to miss is the one hiding in plain sight.

This debate has not come out of thin air. Professor Megan Davis — one of leaders in the Indigenous consultation process that led to the Uluru Statement of the Heart — tweeted at its start: “Statues and monuments erected to slave traders and perpetrators of frontier massacres were raised by all Aboriginal constitutional dialogues”.

Although Cook is in a different category, the debate is not a pale imitation of the movement against Confederate monuments. It’s specifically Australian. The words on the base of the Cook statue in Hyde Park — “Discovered this territory” — are only comprehensible in the context of the now discredited concept of terra nullius, a land empty until discovered by European seafarers.

As with Adam Goodes, the culture warriors of the right rushed to shoot the messenger. From Alan Jones’ threat on Twitter that Grant would “go the same way as Yassmin Abdel-Magied” to Rowan Dean in the AFR whose typically funny-as-a-car-crash column was a monument of its own — a monument to 19th century colonial music hall stereotypes.

More serious was the attempt to write down Grant the journalist and writer as a mere advocate — just as Goodes’ critics discounted his skills as a player because of his advocacy.

Journalists needed to push back. The ABC’s Barrie Cassidy stepped up defending his Wiradjuri and Gamilaroi colleague, retweeting Jones with the line: “Yep. Stan should go back to where he came from.”

To the extent critics engaged with the issue itself, it was by fundamentally misrepresenting what Stan had actually said, such as the Daily Telegraph’s Taliban this and Stalinism that.

Or Jones, again, who on his radio program proffered a Jesuitical exegesis of the meaning of the words “discovered” and “territory” to explain that the words on the Cook monument didn’t mean what they actually say. He then went on to drop Governor Phillip from history with the statement that Cook “was the founder of the first British colony in New South Wales”.

Cook and his monuments — particularly the Sydney statue and the Cook Cottage in Melbourne — have long been contested. When the Cook landing was re-enacted on its bicentenary in 1970, Aboriginal protesters across Botany Bay floated wreaths in the water. The Sydney statue was graffiti-ed with land rights slogans about a year later in 1972 (as it was again over the weekend).

There’s no doubt, Cook was an extraordinary person. He was a key contributor to the globalisation of knowledge in the eighteenth century.

Cook, the monument, has a different history. His adoption by settler Australians was equal part about promoting the glories of the British race and a desire for the colonies to be recognised at the centre of the story of that race. The British Cook supplanted the Portuguese Torres or the Dutch Tasman.

The Sydney statue was cast in England (after a public subscription was topped up by the NSW Government), shipped to the colony and erected in the late 1870s in a ceremony that papers of the day said was attended by 60,000 people — about 10% of the population of the day.

It reflected the political sentiment of those immediately pre- and post-Federation years, a time when the largest selling book by an Australian author (indeed, one of the largest selling of all time) was Deeds that Won the Empire by Melbourne journalist William Henry Fitchett. (Cook gets a mention for his role in the capture of Montreal in 1759.)

It’s a sentiment that remains with us in the wording of the now notorious section 44 of the Australian constitution which sought to preserve the Parliament for the British people.

And like section 44, time has rewritten our reading of the monument and of Cook. We’ve Australian-ised him. In our minds he’s one of us.

Right now, Grant reminds us we’re going through a renewed understanding of Australia, an understanding that human history in Australia didn’t start with Cook, but extends over tens of thousands of years. History didn’t stop and then start again.

I was livid at the garbage that was directed at Grant. When Goodes was made Australian of the Year, I foresaw problems. I agree with his worthiness, but thought it better to wait till a sportsman is no longer playing. It felt wrong to me and I think to many. I would have felt the same about any sporting identity. I am however a great supporter of Goodes for what he has attempted. They hate Stan Grant. He is everything they are not. Articulate, intelligent and a world standard journo. Cook was a great navigator and a superb cartographer. He was also a humane and decent man. I was taught he discovered Australia. I have read much since then. Cook was nowhere close, even among the Europeans and he never claimed to be. I feel a bit sorry for him. He gets the blame for what followed and it is really not his fault. Phillip was a pretty decent bloke and did his best. MacQuarie is both angel and demon. The rest of the governors until Gipps in the shadow Myall Creek were worthless. Now there have been great Aboriginal leaders. Where are their statues? Who knows their names?

It seems that Grant is destined for the same role as many, the acceptable face for the crie du jour.

They tend to have a very short shelf life.