In the aftermath of a change.org petition opposing a performance from the world’s least dangerous rapper and well-intentioned Grammy thief Macklemore at the upcoming NRL grand final, Tony Abbott made it clear that sports fans should be spared politicising of their big events. Sport is, after all, sport.

Pauline Hanson added that people “have had it up to here with the same sex marriage issue” and lamented this foreigner stealing Aussie jobs: “We’ve got so many other great artists in this country that we could actually put up there.”

Of course, Macklemore was announced as the headliner for the final a month ago. The performance of a popular artist’s second biggest hit wouldn’t be at all political if Australia wasn’t currently undertaking an elongated public process that no marriage equality advocate wanted in the first place. Of course, ditching him now, or asking him not to play the song, would itself be very political.

And, of course, as BuzzFeed pointed out, Abbott himself hasn’t exactly shied away from politicising sporting events, and, as Crikey reported yesterday, he has had a problem with charging the public for his sporting fun.

But let’s take his view at face value. Just how well does the argument that sports and politics don’t mix hold up?

Apartheid

“We understood, as South Africans, the significance of sport for white South Africa. It was like a religion. And if you hit them hard, then you were really getting the message across that they were not welcome in the world as long as they practiced racism in sport.”

— Abdul Minty, South African exile, British Anti-Apartheid Movement

The most obvious bleeding of politics into sport is the decades-long boycott practically every major international sporting code conducted toward apartheid era South Africa. Soccer was the to act with FIFA suspending South Africa in 1964 — South Africa suggested sending an all white team to the 1966 world cup and an all black team to the 1970 tournament, but this, surprisingly, failed to win them re-entry. The Olympics followed suit the same year, but it took some time for the rest of the sporting world to catch up. A flurry of sporting bodies expelled or suspended South African teams and/or imposed moratoriums on touring the country from 1970 onward:

- The international cricket council imposed a moratorium on tours to South Africa in 1970 — although this was undercut by the “Rebel tours” that abounded through the 1970s, privately organised and highly lucrative, and Kerry Packer’s breakaway World Series Cricket tournament, which employed South African cricketers as part of their “rest of the world” team;

- The International Association of Athletics Federations suspended South Africa in 1970;

- In tennis, South Africa was ejected from the 1970 Davis Cup — only to be reinstated in 1973 before winning in 1974. Meanwhile, South Africans continued to play in Wimbledon, and the US tennis association controversially allowed a tour of South African players in 1978; and

- Motorsport, golf and rugby union all have mixed records — particularly rugby, who retained South Africa as a member of the International Rugby Board throughout apartheid.

Jesse Owens

In some cases, merely succeeding takes on a political element. In 1936, the Olympic games were held in Nazi Germany and black American runner Jesse Owens managed to discredit the master race theory of the Nazi Party by winning four gold medals. Not that this led to any changes either in Germany or his home country: “When I came back to my native country, after all the stories about Hitler, I couldn’t ride in the front of the bus,” Owens later said. “I had to go to the back door. I couldn’t live where I wanted. I wasn’t invited to shake hands with Hitler, but I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President, either.”

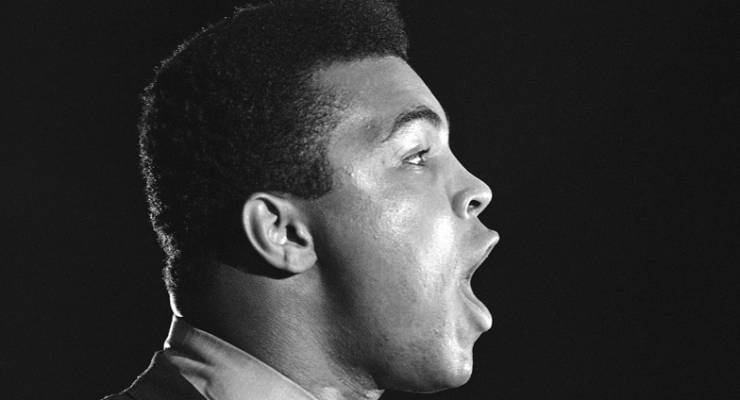

Muhammad Ali

According to former US attorney-general Eric Holder, Muhammad Ali’s great victory “came not in the ring but in our courts in his fight for his beliefs”. Ali famously refused the draft as a conscientiousness objector:

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father … Just take me to jail.”

Ali avoided jail time, but was stripped of his title and his licence for three years. During this time, he spoke on college campuses as part of the anti-war movement.

But sure, Tony. Sport and politics never mix.

omg so much proofreading not done on this piece.

Good piece but the missing words are painful.

Abbott continues to spew inane three word slogans.

Incidentally, when did ‘sport’ become ‘sports’? North America, anyone? Sport is an English word both singular & plural, the added ‘s’ is grammatically superfluous & wrong.

Let’s not forget the Tones is a dyed in the wool Kathlik and implicitly believes that his opinion on most matters is, by divine association is correct and above secular criticism and refutation. Like many shock jocks he is unable to distinguish between opinion and empirical data and facts.

Tones himself turned up at an NRL Grand Final a few years back. God how I wished sport and politics didn’t mix then.

Hypocrite, thy name is Abbott.

Would Tony have supported the international boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics implemented to retaliate against the communist invasion of Afghanistan? Those brave mujahideen, the amazing jihadists welcomed by President Reagan at the White House. Whose side were you on back then, Tony? Or was sport just sport?