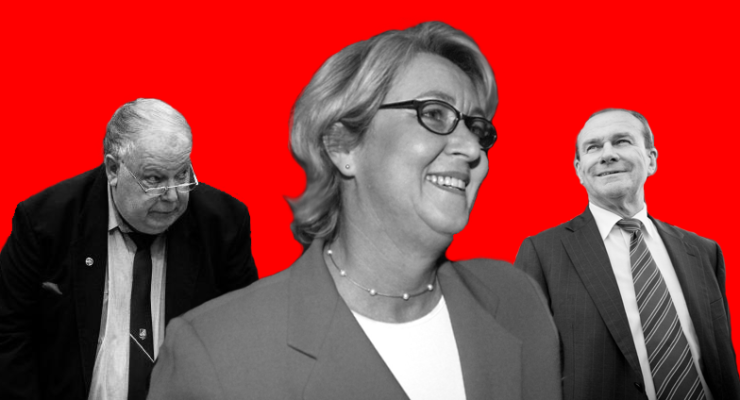

Our piece on Martin Hamilton-Smith, in which we asked whether he was Australia’s biggest turncoat, prompted a wave of feedback from readers about who really deserved that title. So in the interests of completionism, Crikey has talked to a group of Australian political historians about their favourites. Here’s our first installment, in no particular order:

Mal Colston

Colston was an ALP senator and Doctor of Philosophy, elected 1975. After 20 fairly nondescript years — aside from perpetual questions surrounding his use of expenses — and frustrated by his lack of progress up the ranks, he jumped ship in 1996. He quit the ALP and stayed in the Senate as an independent, giving his vote to the new Howard government, which they needed for the privatisation of Telstra (a policy vehemently opposed by Labor at the time). He was rewarded with election to Senate vice president for his trouble.

“He was bitterly and publicly loathed by John Faulkner and Robert Ray,” Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History at ANU told Crikey. “As far as I could see, he was utterly opportunistic; it had nothing to do with ideology, I think it was entirely about getting that placement.”

Soon after his defection (over which Ray memorably called him “the quisling Quasimodo from Queensland”), in 1997, Colston was issued with 28 charges of misusing his parliamentary expenses by the Department of Public Prosecution. His cancer diagnosis resulted in the charges being dropped, and he died in 2003.

Sir Jack Egerton

“My favourite is Jack Egerton,” Biongorno told Crikey. “He was never in office, but really, he was as good as; he was basically running the Queensland Labor Party, right through the Bjelke-Petersen years.”

Egerton was a left-wing union leader in Queensland from the late-’60s to the mid-’70s, who simultaneously headed the Queensland Trades and Labour Council and the ALP Queensland Central Executive. He was a close friend and ally of Gough Whitlam, supporting him when he was nearly expelled from the party, and was considered by some to be his right-hand man in Queensland.

Then, a year after the Whitlam dismissal, he was offered a knighthood by new prime minister Malcolm Fraser. Amazingly, he accepted.

“He was very much left faction figure and eventually he accepted a knighthood, which of course is totally contrary to Labor Party policy,” Bongiorno said. “And just for the icing on the cake, it happened to be conferred by Sir John Kerr, the same governor-general who had sacked Whitlam. There’s a wonderful book called Socialism Without Doctrine, and the English translation used this as the image.”

Cheryl Kernot

The Australian Democrats had been steadily building a presence in the Senate for just under 20 years when Cheryl Kernot became leader in 1993.

“She was a good leader, articulate, a good media performer, a good negotiator,” Professor Jenny Stock of Adelaide University told Crikey. “At one point out of [all] party leaders, Kernot was more popular than Howard or Beazley — which, to be fair, may not have been that hard at the time.”

In 1996, the Democrats had one of their best ever results and ended up with seven senators and the balance of power. But their position was weakened slightly after Mal Colston’s defection allowed the government to pass legislation without necessarily needing their involvement — and in 1997, Kernot announced she was leaving her party and the Senate, and running for Labor.

“This was shocking for the Democrats, who were doing as well as they ever had been,” Stock said. “And of course, for minor parties, the leader is absolutely crucial. Kernot said she wanted to be closer to where the power was.”

“She did the honourable thing in a way, though. She quit the Senate and ended up running for Labor in the marginal lower house seat of Dickson. But of course the problem with being a turncoat is, you’re out of favour with your old party, and you may not end up being all that welcome in your new party — particularly Labor, who have such set process by which people enter and progress.”

Of course this wasn’t the full story, as a plucky little two-year-old called Crikey would end up being the first to reveal, she and Labor’s Gareth Evans had been having an affair.

“The press of course had a field day, which is always a particular problem with high-profile women,” Stock said. “Kernot didn’t end up doing all that well for Labor.”

Kernot ended up losing Dickson to Peter Dutton in 2001.

Check back tomorrow for the second part of our series.

I don’t see what the big deal is with these bastards eating each other. It’s quite refreshing actually. The real scumbags are their “loyal” political colleagues screwing us over.

My nomination for a turncoat is Albert Field, who was nominated by Joh Bjelke-Petersen-Petersen to replace a Labor senator who’d died in 1975. As an irony, the person the ALP nominated for the casual vacancy was Mal Colston.

Field was a member of the ALP, but was very much a social conservative, vowing never to vote for the Whitlam government.

He was on leave from the Senate at the time of the Whitlam dismissal, there being some doubt that he was eligible to sit in the Senate owing to section 44 banning people receiving profits of the crown to sit in parliament. The opposition had refused to provide a pair, so they had a majority and were able to defer supply.

My vote as well, Wayne.

Yes, it’s a great tale. Too impossible to make up.

I wish that there were some other motive for Kernot’s abandonment of her colleagues and electorate than having been love bombed.

And by Gareth Gareth Garrulous !

Sir John Kerr put in a diva performance in turncoatism. A once faithful friend of Gough Whitlam he was the one to butcher him. Bastard.

Thanks for that cover pic – I can’t quite put my finger on the begging/cur metaphor – sort of a McAuley glyph.