If you ask me, the dominant discussion around mental ill health is a guarantee of more mental ill health. Of course, you didn’t, but I have been wont in any case to provide an answer: popular journalism, political speech and public campaigns on mental health are faulty. Both conversation and policy are led by a faith that “awareness” is a primary defence against illness — nowhere has this placebo been more adamantly served than in the ABC’s “Mental As” programming, which delivers us the message that “stigma” is the cruellest cut of all.

Stigma is a problem, but to declare this with such centrality is to imply that stigma’s absence is a cure. Yes, it is unhelpful when the common disorder of depression is perceived by some as indolent self-pity. No, if we remove the “stigma” from the social body and swap it with “awareness”, the best medicine has not been prescribed.

What we will get, at best, is a load of destigmatised, aware sad people who can neither afford the psychiatric assistance TV personalities trial and recommend nor access it in their outer-suburb or region.

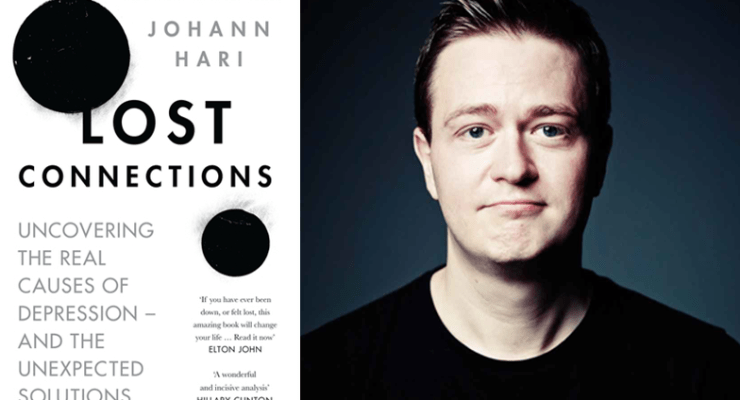

The view of mental illness is made possible by the faith that our misery is “chemical”. This is the idea Johann Hari seeks to challenge in the new blockbuster Lost Connections.

Good. A popular book to take the scientific advocacy for the non-chemical case from eminent psychiatrists including Allen Frances or Horwitz and Wakefield — their 2007 plain-language book The Loss of Sadness is recommended — is what the West needs. A book whose first-person, non-academic form permits it to go beyond mere medicine? Great. While Frances and others are bound to review only nosology (the classification of diseases) Hari can not only make the case that depression is not, in all cases, chemical, but that it can be a response to social conditions.

Clear links between poverty and depression notwithstanding, the idea that It Can Happen To Anyone remains common. Organisations like beyondblue are reluctant to acknowledge poverty as a forecast of depression. They retain the view that the disorder comes from within. The view that the disorder may also derive from without is only permitted in campaigning when advocacy groups make that relentless demand. That we have seen advertisements and read accounts of depression’s disproportionate prevalence among Aboriginal and LGBTIQ people is entirely down to the activism of those groups. These are the two exceptions to the It Can Happen To Anyone rule.

It can happen to anyone, but it happens disproportionately to those of social and/or cultural categories whose everyday survival is endangered.

That Hari has sought to elaborate on the bleeding obvious is marvellous. The “depression always comes from inside us” view is an unscientific rationale that refuses to see depression itself as a symptom of societies that are ailing. So, I took to this book with gratitude, its jacket endorsement from Hillary Clinton and author’s history of plagiarism notwithstanding.

Hari does challenge the powerful, policymaking view of depression as a thing arising in the individual. This is commendable, as are his efforts to tie the thing back to the social. Yes, neoliberal techniques of economic organisation have produced conditions in which misery prospers. Yes, this misery has been codified by the same conditions that produced its “solution”: antidepressant medication. Hari is not keen at all on drugs. I am not so keen on his anti-drug fervour.

Nor are many psychiatrists. While Hari says that he does not wish to deny those with depression their diagnosis or their drugs, he does make a passionate case against both. Which would be permissible if this book was offered only as bold plea for reason — like this one — and not as reason itself.

Hari is so keen to see depression as the product of an alienated and unequal age, he has little to say about the distinction that scientists like Frances, and even Hippocrates, make clear. It was, right up until the neoliberal era, both medical view and practice that depression fell into two kinds: one from the inside and one from the outside. Hari has so much interest in the latter, the former is occluded in this ardent account.

The book demonstrates that the practice of science is very often compromised by profit. It reasonably challenges some of the unreason that feeds us so very many antidepressant drugs. But, not all of Hari’s book is pure reason. If you’re going to use your own journey through psychiatry as a means to perceive psychiatry, you need a load of disclaimers. Sure, Hari finds studies and esteemed experts who support his mostly reasonable view. He will also find, I feel certain, readers who’ll just want to go off their meds after chapter one.

Plenty of others with plenty of distinctions have made this case against Hari. Goodness, I wish that they were not compelled by the author to do so. What might have been a theoretical book that urged us to think of the classification of depression in a better way masquerades as a “scientific” work. Moreover, one that makes most shrinks seem like stupid people who completely ignore the social. Not, in many cases, doctors who work to the biopsychosocial model of illness.

My reading and conversation with psychiatric scholars these past ten years has persuaded me that biopsychosocial must again become as foundational in diagnostic practice and research as it was in the past. You elevate one part of that, and the others are eclipsed. Sure, depression has been for far too long attributed to the “bio” alone. Then again, anorexia, a disorder known to have biological markers and believed by many scholars to have a biological basis, has been understood as almost entirely social (skinny models are to blame etc) and research, and patients, have suffered.

I wish he’d toned it down. I wish there was a little less Hari here. However much one supports a very sensible opposition to “destigmatising” or to “awareness” of depression as a chemical thing that can Happen To Anyone, one cannot fully support a book about a self that purports to be about everyone.

If you’d like to talk about any issues with your mental health, you can reach Lifeline on 13 11 14, or beyondblue on 1300 22 4636.

My Personal Story Off and then On Bipolar Meds: 1989 to 2018

1989: age 19 onset of bipolar symptoms: disruption to relationships, career and finances due to manic and depressive moods. This raged for the next 18 years.

2005: age 36 first bipolar medical diagnosis after attending psychiatric sessions for 6 months. Diagnosis confirmed through second opinion of world leading psychiatrist Prof Isaac Schweitzer.

29 March 2007: after 2 years of resistance I finally started taking Lithium. Very positive results stabilising moods which enabled me to work the regular hours of a job again. Since then have taken Lithium daily for 10 years and added Lamotrigine in Dec 2007 to give more protection against depression. It should be noted that these bipolar medications can have serious harmful side-effects; although I have not suffered any that I am aware of or have shown up in regular blood tests.

Summary: 19 years with no symptoms; then 18 years bipolar raged without medication; then 10 years on bipolar meds and have achieved really good mood stability with access to energy and creativity that I feared were at risk of becoming impaired if I started taking meds.

I would recommend people with disruptive moods seek out an opinion (or a couple of them) from a healthcare professional, and also consider medication. For me it has been a miracle and perhaps it will work wonders for you as well.

David Barrow

Thanks, David. Let’s also recommend adequate spending on research and treatment for all. As I understand it in conversation with psychiatrists and advocates, bipolar disorder with its relatively low prevalence (compared to depression/anxiety) is one of the conditions that “slips through the cracks”. Which is to say, people who can really benefit from the most help receive it the least.

I am so very happy to learn that you have achieved an acceptable balance with your health. This is the thing, right? People can. Largely, though, it’s a matter of luck when it comes to mental health. We want for everyone what you have achieved.

Hi Helen, thanks for engaging in posts in the comment section. Some trickle down medical stats say that bipolar is actually quite prevalent at about 1% to 2% in the human population. From what I’ve read over a decade ago, a persistent difficulty is the delay in initial diagnosis, with a 10 year delay not uncommon. In my individual case, I had a sense that something was awry with my moods around the time leading ‘manic-depressive’ researcher Kay Jamison visited Melbourne University to present a public lecture in 2000. It was still another 5 years before I sought a medical evaluation after I gained more insight observing a friend who was getting more and more out of control with a bipolar condition. With recent celebrity disclosures of the bipolar condition (Catherine Zeta-Jones; Russell Brand etc) perhaps there is a risk of some initial overdiagnosis now where the assessment relies on recounting personal history. Although I expect presentation with symptoms of the spectrum of depression or mania would be alternative compelling tells, as well as the consequences of episodes that involve risk-taking and/or even self-harming.

It seems to me that underdiagnosis is a much greater problem than perhaps fashionable overdiagnosis. Again from my reading of over a decade ago, substance abuse is a vast problem for people with a bipolar condition as a ‘self-treatment’, many of whom may not have had an accurate diagnosis. I have also read that there is a suicide lifetime ‘success’ rate as high as 20% for an untreated or poorly treated bipolar condition.

In this serious context, raising awareness of the bipolar condition through personal stories can be helpful for people to obtain medical assessment(s) and consider taking effective medication.

For all the insight and empathy-awareness that came from the 18 years between 1989 and 2007 of whiteknuckled, untreated rapid-cycling bipolar chaos, I would have preferred that someone encouraged me to explore medical help earlier. In my case, it would have saved me much needless suffering. Helen, if I’ve understood your position correctly, your attack on raising awareness through people like me telling our personal stories is not helpful for others finding help.

I do not dispute this at all, D. Yes. A clear (and not exploitative or romanticised) account of bipolar is helpful. However, this article is about the highest prevalence disorders and the ones so often discussed: depression and anxiety.

While I agree with some of Hari’s impulses (he wants to show depression as a symptom of society) I do not agree with all (he wants to get people “off drugs”. Seriously. I do not know why he feels so able to conclude that drugs are ineffective. I get that depression may be in many cases caused by life. My own, for example. To go on to find doctors who lump all antidepressants in together, and all depressives, and say “they just don’t work, and are dangerous” is not a great place to arrive at, in my view. Hari is good and bad).

The “depression can be social” is a good argument in both an MH and broader policy context. But, not how he does it.

Similarly, awareness raising can be good, but not how it is usually done. Friends with bipolar tell me, for example, they find something like Silver Linings Playbook offensive for its “oh, you sexy genius” ways, or see the elevation of “successful” people, like the late Carrie Fisher or Fry, as a bit of a deception. Those guys can get help. A load of people can’t. A bipolar friend was so upset a few years back with Mental As on ABC, I started to watch the thing and got just as angry as him. He was all, “When I am on a downswing, ‘stigma’ is the least of my problems.” That stigma was discussed as being a big problem for people with bipolar (I know it is in many cases) to the point of overemphasis has the effect of making people like they are truly helping just by understanding etc. This really diminishes the political will desperately needed to make the life lived with bipolar less uneven.

Anyhoo. I know bipolar folks often have periods of “depression”. Just to be clear, this depression is not the sort I am discussing here or the sort Hari describes in his book. It’s the medical category.

And, seriously, you really have done bloody well and you get a Mental Health gold star from me.

Well, I think bipolar sufferers get a Mental Health gold star when we consider getting more information from a healthcare professional about the turbulent mood waves. And if a diagnosis is confirmed, I found keeping a mood diary helpful and eventually trialing the gold-standard medication of Lithium even more helpful. These treatments don’t work for everyone but it sure helped me.

I can’t recall any high-profile bipolar sufferers when I was in the first decade grip of the illness. I went to my local GP in about 1990 and said I felt really down. He asked ‘why are you really here? Come on, there are sick people waiting to see me’. Reluctantly he ran some blood tests and of course nothing showed up, as the bipolar condition is not determined in that way. After that I felt doctors were not going to be so helpful. An extraordinary anecdote. Times have changed.

I feel I would have benefited in the earlier stages of my condition if I had seen a celebrity-stacked Stephen Fry type doco on bipolar. Or even a Silver Linings Playbook (which director David O. Russell said he made as a gift for his 18 y.o. bipolar son). And the discussion around these. If the present me sat down with the me in my 20s and raised insight / awareness through my personal story then (1) there would likely be a tear in the time-space continuum that could destroy our part of the universe (sorry) and (2) I could have helped me to find treatment earlier.

Helen, in 2016 you wrote: “I feel for Guy Pearce. But, as a person who once had a diagnosis of PTSD that led, as such things overwhelmingly do, to complete professional meltdown, I know that seeing a handsome dude who makes about five feature films a year talk about his struggles with anxiety would just have made me feel more unproductive and worse.”

Me, I prefer to hear stories like Guy Pearce. That raising of awareness can help to reduce stigma and encourage those who could benefit to seek out treatment. Perhaps Guy Pearce became more productive making movies because he is receiving effective treatment? Or just suffered less in not dragging himself through the process with a needless burden. In the case of bipolar, I get enough pills to last me 3 months for about $7. But first you need to know that these pills can help you.

Helen, if you want to frame ‘awareness’ as some ineffectual exercise on Beyond Blue brochures then I’d encourage you to think more broadly.

You also say your article is about the “highest prevalence disorders and the ones so often discussed: depression and anxiety”. Um, if a spectrum of bipolar occurs in 1 to 2% of the human population, that’s over 70 million people (200,000 Aussies). A lot of people who could benefit from awareness, even if it breaks through to them with the dazzle of ‘celebrity’ lives: Stephen Fry, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Richard Dreyfuss, Carrie Fisher, Linda Hamilton, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Adam Ant, Sinead O’Connor and Russell Brand… and perhaps Robin Williams.

Take your points, D. But, am not striving to say that depression is more “important” than bipolar. Just that it is much more widely felt. An estimated 25% of the population is more than 2%.

I understand that you and others have felt great gratitude where stigma is reduced. My only point is that this helpful thing is often posited as a solution.

My other point is that real focus on everyday people would tend to be more helpful not only to everyday people but to policymakers, who have largely begun to believe in inspirational accounts themselves as solution.

I really mean that you are admirable in the way you have dealt with your diagnosis. I think your story is one better to be told than others.

Also, I am really not disagreeing with you. Just saying that in the context of the close media and parliamentary relationship. other things need to be said.

Again, thanks so much for your comments, which are great. We only have different views on effectiveness. And, again, I am talking here about depression, the topic of Hari’s book. The same does not go for all diagnoses.

To be fair, perhaps I was not so receptive to insights in my 20s. A flatmate diagnosed me as “bipolar” in 1993, as flatmates are wont to do. This came after a kitchen dispute. And then she did not speak to me or acknowledge my presence for the next few weeks until I moved out. Again not unknown in flatmate wars… except she was a 30 y.o. psychiatrist at the time. And I just Googled to find she has gone on to a steller career since then. Perhaps her empathy has improved as well (or awareness could help with that). Alas her diagnosis was completely dismissed by me in the non-clinical context of the share-house… and her couch-side manner.

Helen, sorry I’m just not understanding your comments:

“Anyhoo. I know bipolar folks often have periods of “depression”. Just to be clear, this depression is not the sort I am discussing here or the sort Hari describes in his book. It’s the medical category.”

You do realise that a bipolar condition is marked as significant variability between moods described at the extremes as Mania/Hypomania and Depression. And as far as I understand medication that is used to treat unipolar depression can also be used to treat bipolar symptoms, although generally only for the acute phase as after the ‘kick-start’ depression medication can itself trigger mania/hypomania? Further, the conventional view is that the depression aspect of the bipolar condition is ‘medical’ — which can also be triggered by societal events of trauma, particularly after a build up of traumas (the poetic ‘kindling’ effect) —

according to the sort of awareness literature available through Beyond Blue which you seemed opposed to. And also an understanding in my lived experience, as one individual case.

Helen, you seem to be getting out a utilitarianism slide rule out when you say: “Just that it is much more widely felt. An estimated 25% of the population is more than 2%.” It is true that 2 billion humans is more than 76 million (10 million Aussies is more than 200,000). But both are heaps, mate.

When liberal politician Andrew Robb disclosed in 2011 his long-running problems with depression and its effective treatment, the media and parliamentary personalities intersected. I believe Robb’s high-profile disclosure helped reduced stigma and encourage depression sufferers to seek a mental health assessment… Notwithstanding the facet of Robb’s book that the disappointing Mark Latham chose to focus on for attention.

The psychologist’s mental health diagnostic book

With the names writ under

does it make me well I wonder?

Or more intelligently mad.

if you want to talk about mental health issues to make has been politicians

happy few free to contact beyond blue appointments restricted to ousted politicians – helps them get over their problems

I don’t think this very often about Helen’s work but, that is a good article. I have spent many hours discussing such things with my Professor of Psychology neighbour. Every person/patient is different and to even begin to understand the causes of, particularly, chronic depression, one must spend a lot of time getting to know the subject as there are as many causes as sufferers. Nothing pisses me off more than when a person who is in the public eye, and who suffers a few months of being depressed, suddenly becomes a spokesperson for the condition. It is almost like a good career move. I know that it can help the public develop an understanding of the complaint but if the celebrity was a life-long sufferer of chronic depression and or anxiety it would have more meaning.

“I don’t normally like Helen, but” continues to be my favourite response after some years of reading it. Many thanks!

Very useful article Raze, thanks.

No wuckers, Smithy.

Helen – part social cause of mental illness ,someone has been there before you – see Hogarth’s – Gin Lane