It’s about Greater Sunrise. It was always about Greater Sunrise. The Timor Sea boundary agreement has now been signed in New York, but the key to the dispute — the $50 billion Greater Sunrise liquid natural gas field — remains unresolved.

Timor-Leste has argued for many years that the agreement which saw the joint exploitation of the Timor Sea’s oil resources was unfair and illegal under the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It has made this argument based on the “median line” principle in which, under UNCLOS, the sea boundary between two countries should be drawn at the median point.

Had this happened, virtually all of the Timor Sea oil and gas resources would have accrued to East Timor. Moreover, under UNCLOS principles, the largest proportion of the huge Greater Sunrise LNG field would have also fallen within East Timor’s waters. Under the 2006 agreement with Australia, it did not, although Australia had offered to split revenue from the field 50-50 with East Timor.

East Timor’s then prime minister, Xanana Gusmao, argued that East Timor should not have to settle for half of what it should rightly own all of. At the bottom of his position, however, was much less a question of territorial sovereignty and much more his vision for processing the LNG on an as-yet built facility on East Timor’s south coast.

This was in contrast to processing the LNG at a plant near Darwin. Backfilling the depleting oil pipelines from the Timor Sea would have been the quickest and easiest option.

This south coast facility was intended to kick-start East Timor’s petro-chemical industry and provide the tiny half island nation with an alternative economic source into its longer-term future.

The lead partner in the Greater Sunrise development program, Woodside, objected to the south coast facility, noting that a pipeline would have to cross a deep sea trench.

Others also pointed to the cost of developing such a facility — around $4-5 billion — and the lack of infrastructure and suitably trained people in East Timor. Some also noted the possibility of sovereign risk, should East Timor’s politics take a more nationalist turn.

Woodside responded by saying it would build a floating LNG processing platform. Gusmao responded by saying that if Woodside did not agree to the south coast development proposal, East Timor would tear up its 2006 agreement with Australia and seek a permanent maritime boundary to resolve the issue.

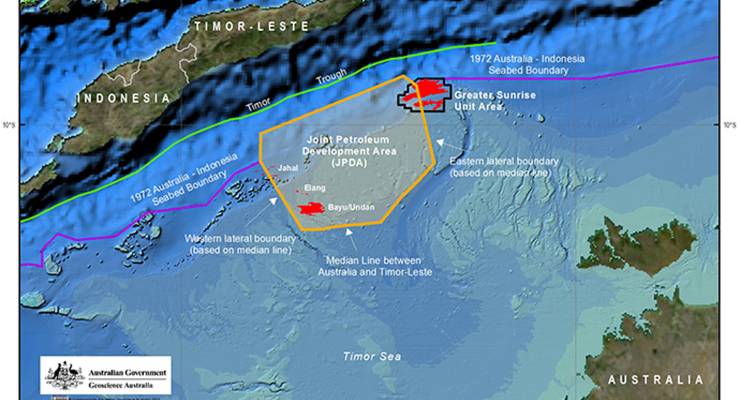

The Permanent Court of Arbitration eventually ruled in East Timor’s favor and a median line boundary between the two countries has now been agreed. However, because the “lateral” boundaries — those at either margin of the agreed area — were decided in an agreement between Australia and Indonesia in 1972, these have not altered.

As a result, the majority of the Greater Sunrise field still lies within Australian waters. If East Timor was to claim Greater Sunrise, Indonesia would also have to agree to alter its sea boundary with Australia, which to date has not been a part of the negotiations. The agreement signed in New York overnight was to have finalised the whole of the Timor Sea issue.

But parts of the agreement had not previously been seen by the East Timorese delegation, including a decision to, in effect, process the Greater Sunrise LNG near Darwin.

The most important part of the agreement, and that which precipitated a bitter dispute with Australia, has still not been signed and remains contested. East Timor might now seek to bring Indonesia into discussions to redraw its own boundary. This could see the re-drawing of the Australia-Indonesia sea boundary very much more in Indonesia’s favour, given it currently disproportionately favours Australia.

But, in the end, the issue was and remains about access to the Greater Sunrise revenues to prop up East Timor’s economy for more than the next decade which, under current spending, will exhaust savings from the Timor Sea oil. The problem is that, under any arrangement, the royalties from the Greater Sunrise field will only amount to around $8 billion, which will only stave off the inevitable for a few years.

Developing a south coast refinery could give East Timor a new lease of economic life. Or, as suggested by East Timor’s government, it could finance the facility itself and risk blowing all but the last of its savings on a white elephant.

So, East Timor’s economic position has not altered and the Timor Sea agreement has not produced the results that East Timor desired of it. How East Timor now proceeds may be determined by the outcome of the forthcoming May 12 elections. One suspects the two main coalitions competing in the elections could have different views on how to finally settle the issue of Greater Sunrise.

Professor Damien Kingsbury is Deakin University’s Professor of International Politics.

The way in which Australia’s noble leaders helped Timor-Leste to achieve its penurious independence just warms the cockles of the heart. Get them away from Indonesia and then grab their resources. Having actually visited and made friends in Timor-Leste, I would like to see the robbery recorded as robbery and the thieves punished as thieves.

With respect Damien, UNCLOS does not require the boundary to be at the median line between Australia and Timor-Leste. You appear to be referring to Article 15 of UNCLOS, which limits the territorial sea between the countries (not the right to resources below the seabed). However, even that article expressly says that the median line method does not apply “where it is necessary by reason of historic title or other special circumstances to delimit the territorial seas of the two States in a way which is at variance therewith”.

Part VI of UNCLOS has a completely separate regime for delimitating continental shelf claims, which does not start from a median line presumption like the territorial sea does. Broadly, UNCLOS and, before UNCLOS, customary international law, give three options as to how to set the seabed boundary. One is the median distance between the coastal baselines. A second is the natural prolongation of the continental shelf to the point where it starts to drop off into the deep sea. A third is the natural seabed boundary. Each method is equally valid, but historically, for ownership of subsea resources, the natural prolongation of the continental shelf has a higher degree of support as the seabed resources were considered to be an extension of the land, while for rights to the water column (e.g. fishing), the median line was more commonly accepted.

The issue is the underwater topology. Working from South to North, the Australian continental shelf stretches relatively shallowly most of the way to Timor. The seabed then dives deeply into the Timor Trough, before rising sharply to the Timor coast. The bottom of the Timor Trough, which arguably is the natural seabed boundary, is less than 50 nautical miles from the Timor coast.

The 1972 Australia-Indonesia seabed boundary is based on the natural prolongation of the Australian continental shelf, but Australia only enforces water column rights to the median line, particularly in the area east of Ashmore Reef, where a separate MOU between Australia and Indonesia permits some traditional Indonesian fishing rights.

The JPDA (and its predecessor agreement with Indonesia) set boundary lines, and internal sharing boundaries within the JPDA, based on the three different methods of delimitating the sea-bed boundary. The Southern boundary is the median line and the resources in the Southern zone were originally shared 75/25 to Australia. The Northern zone, which is the area to the North of the Australian continental shelf as it falls into the Timor Trough, was shared 90/10 to Indonesia (originally, prior to Timor-Leste independence). The central zone was shared 50/50.

The Eastern and Western boundaries of the JPDA are fixed by the boundaries between Indonesia and Timor-Leste, being lines running perpendicular from the coastal baselines at the land borders between those countries.

As the map in your article indicates, most of Greater Sunrise falls outside of the JPDA. It is governed by the Australia-Indonesia seabed boundary. There is zero prospect of Australia agreeing with Indonesia to redraw that boundary, and no basis that I can think of in international law for Timor-Leste to move its Eastern seabed boundary with Indonesia further to the East to capture more of the Greater Sunrise field (which would necessarily involve Indonesia ceding sovereignty over the seabed to the South of Pulau Leti – it is not going to happen).

Whilst there are a lot of reasons to have sympathy with Timor-Leste over the way they have been treated both by Indonesia and Australia, on this point neither geography nor international law are on their side.