Way back in the 1920s, Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach formalised a scheme for diagnosing schizophrenia that involved showing abstract patterns of ink-blots to patients, and drawing conclusions about their mental state from how they interpreted the images. Where one subject sees a butterfly in the enigmatic splatters, maybe you see a pair of wolves pole-dancing, or whatever, it’s on you.

The WikiLeaks organisation has operated as a kind of political Rorschach test since at least 2010, when it exploded into mass consciousness with a video, “Collateral Murder”, of journalists and bystanders being executed by a US helicopter gunship over Baghdad. Prior to that, the organisation’s publication history reads like a quasi-random global tour of scandals and hidden violence: operating manuals from Guantanamo Bay (2007), Chinese repression in Tibet (2008), Australia’s notorious and short-lived internet filter blacklist (2009), and dozens of others.

No one but those most closely involved understood that the appalling Collateral Murder disclosure was just the first of a series of four major transparency dumps — including the 2010 release of the Afghan and Iraq war logs and then the quarter-million haul of State Department cables — on the true nature of US military and diplomatic conduct.

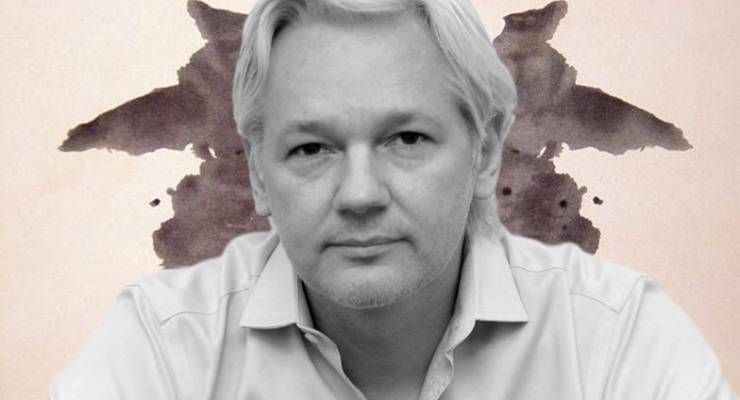

This malignant scatter of ink-blots was easy enough for most people to read: the disclosures were clearly in the public interest, given the distance between the officially curated version of the United States’ saintly presence in the world and the ugly raw material that WikiLeaks had laid out online. Editor Julian Assange made the cover of Time magazine, and front page after front page unfurled with sensational headlines as the inner workings of empire were briefly laid bare. Partnering with reputable outlets like The New York Times, Le Monde and The Guardian provided a measure of legitimacy — and safety — to the tiny guerrilla publisher.

[Razer: journalism is not a crime! Except, you know, when WikiLeaks does it]

President Obama’s composed demeanor masked a deep fury within the US national security establishment, however. More than 5 million people across public and private sectors in the US hold security clearances, forming a kind of government within the government, and this institution holds grudges. A Justice Department investigation “unprecedented both in its scale and nature” was launched, and remains live to this day.

Despite the extraordinary pressure brought to bear on the organisation, its staff and volunteers, the publications didn’t let up: the “Spy Files” exposing the global surveillance industry, leaked chapters from the secret Trans Pacific Partnership negotiations, NSA spying operations against the United Nations Secretary General, and the latest publication revealing the CIA’s offensive cyberweapon stockpile, with thousands of careful redactions to ensure that no dangerous code was released. By any measure, it’s an extraordinary publication record, all of it timed for maximum public impact.

Before we hold up the next card so you can consider the ink blots, there is a further dimension to the campaign against WikiLeaks that needs bearing in mind. In the wake of the huge 2010 disclosures, a seedy coalition of infosec hustlers and former military intelligence people drew up a pitch document outlining proposals for how to destroy the publisher. We know what was in the slides because they were leaked — by WikiLeaks — and their attack strategy is highly instructive:

Feed the fuel between the feuding groups. Disinformation … Submit fake documents then call out the error … Media campaign to push the radical and reckless nature of WikiLeaks activities. Sustained pressure. Does nothing for the fanatics, but creates concern and doubt amongst moderates …

This coalition of companies — Palantir Technologies, HBGary Federal and Berico Technologies — disintegrated as soon as the sunlight of disclosure hit their excruciatingly “cyber” Powerpoint slides, but the episode remains valuable for its central proposition: to burn off WikiLeaks’ protective armour of moderate journalists, funders and supporters, while destroying the reputations and trust networks of those closest to the heart of the organisation.

Some vastly more professionalised version of this strategy must have been in play since then, with the results, to their credit, very much in line with the predictions of the HBGary cabal. So much so, that when we hold up the next card, it’s quite likely that instead of seeing ink-blots that look like a publisher, many will see a front for Russian intelligence agencies led by a sex offender who single-handedly delivered the White House to the repulsive Donald Trump.

It is hard to recall the conduct of a legal case more damaging to the interests both of the accusers and the accused than the Swedish government’s botched investigation into sexual assault allegations against Assange dating back to 2010. Italian journalist Di Stefania Maurizi has conducted a careful analysis of the British government’s alleged manipulation of due process, exposing an unseen side of the case.

“Please do not think that the case is being dealt with as just another extradition request,” wrote a lawyer for the UK Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) in 2011, without explaining why, or why the CPS would spent the next few years arguing against their Swedish colleagues questioning Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy in order to resolve the matter. In 2013, when Swedish prosecutors proposed to drop extradition proceedings against Assange, it was the CPS who persuaded them to continue.

In 2017, having finally questioned Assange after refusing to do so for more than six years, the Swedish authorities dropped the investigation altogether. Both the accusers and the accused were denied any chance of justice through the incomprehensible delaying tactics of the prosecutors in both countries.

One of the more recent document drops listed on the WikiLeaks publication archive is the one titled “19,252 emails, 8,034 US Democratic National Committee (DNC) database”. It’s dated July 22, 2016. In it, you will discover how the Democratic Party machine cooked their own primary process in order to ensure that the powerful Bernie Sanders insurgency was derailed, clearing the way for Hillary Clinton to win the nomination. In the aftermath of having run the only candidate that Trump could conceivably have beaten, and with apparent determination to avoid taking any responsibility for their stunning loss, the Democratic establishment found an easy target for their rage. Not the people who ran the corrupted nomination process, obviously, but the people who disclosed it.

In April 2018, the DNC filed a lawsuit against the Trump campaign, the Russian government, the hacker alleged to have infiltrated the Party’s mail server, and WikiLeaks. The true scope of attempted Russian manipulation of the 2016 US presidential election may become clearer with the conclusion of special counsel Robert Mueller’s sprawling investigation, or it may never be known. But it is clear at the outset that suing WikiLeaks — for simply publishing the emails — is a high-risk strategy with potentially disastrous consequences. If WikiLeaks is liable, then so is every other publisher that recognised the public interest in reporting on the contents of the emails at the time.

And so here we are. With a handful of important exceptions, the penumbra of moderate WikiLeaks supporters, journalists, publishers and advocates are long gone. In their place, a small cohort of disaffected former colleagues and peripheral associates have eked out a dismal career writing online hit-pieces on a guy now ending his sixth year trapped in what the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention described in 2016 as being in violation of multiple Articles of both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

I’ve spent enough hours in that embassy over the years to be really unsure I’d have lasted this long. You may genuinely believe that WikiLeaks is now just a cipher for the Russian FSB, or find the allegations of collusion with high-level creepy-crawlies within Team Trump impossible to forgive, or wish that Assange would pause and reconsider sometimes before opening up his Twitter client. But when I look at these stupid inkblots all I can see is an Australian citizen, a long way from home, deserted by his government and targeted by some of the most powerful people in the world for having taken up the Duke of Wellington’s 1824 exhortation to “publish and be damned”.

If you see something completely different I can hardly blame you, but it’s dangerous to start assessing whether or not we think human rights should apply based on our assessment of someone’s character.

In testimony to the US Senate’s Judiciary Committee in May 2017, then-FBI Director James Comey confirmed in unambiguous language that Assange had made an entirely rational decision to seek the protection of political asylum back in 2012: “He hasn’t been apprehended [by US authorities] because he is inside the Ecuadorian embassy in London”. Senior Trump administration officials, from the former CIA director Mike Pompeo on down, have made it abundantly clear that WikiLeaks is still in the crosshairs.

The consequences of the isolation and attempted destruction of WikiLeaks are broad. In a chilling and prescient article in 2013, the Freedom of the Press Foundation’s executive director laid out the methods by which “virtually every move made by the Justice Department against WikiLeaks has now also been deployed on mainstream US journalists”.

WikiLeaks’ famous byline — that “courage is contagious” — now invokes the unpleasant possibility that cowardice is too. The courageous alternative is to agree to set aside our differing interpretations of the inkblots for the moment and demand, in unity, that attacks on publishers are ultimately attacks on us all, and that the persecution of WikiLeaks must end.

Absolutely f***ing superb, former Senator.

I have only one thing to add – “FINALLY!!”

Thanks Scott. Have really enjoyed a few pieces penned by you since leaving parliament.

I’m not sure whether to laugh or to cry, and can’t understand why so many people can’t see that the western world is on the precipice in so many areas, politically, economically, climatically.

And to me, it’s because of the unfettered right for right-wing “media” to poison the well. Print lies, deny science, advanced vested interests, demonise everyone who gets in the way, use big money to advance and normalise this agenda, water the resulting fungus garden with attention and cross-promotion so that it quickly becomes far bigger and self-supporting than the original corporate owned outlets that spawned it all.

All progressive movements have to fight against this wall of fungus, and yet so many progressives still cling to the dream of an unregulated free press as if all journalists and publishers are noble and lying propagandists will be killed by the sunlight of freedom. This is so obviously untrue at this point, and still they cling. It’s like the hardcore free marketeers still clinging to the efficient markets hypothesis, and even more damaging.

Strange how nothing secret about Putin and his oligarchs ever gets leaked to Wikileaks.

Your regular reminder the Greens have become a sad joke of a political party and are rapidly circling the drain.

Patently incorrect. If you bothered to do your own research, you’d find they have published plenty on Russia, going back years.

Just go to Wikileaks, find the search function, and type in “Russia”.

Oodles the last time I did it. Not all ‘unfriendly’ to Russia, but plenty that are.

Whilst the detention is arbitrary, and the precedent unacceptable, there aren’t ‘allegations of collusion with high-level creepy-crawlies within Team Trump’. Assange was in contact with Don Jr, Wikileaks held the documents (having informed Roger Stone & Rudy Giuliani they would be leaking earlier) until an hour after the access Hollywood tape leaked, and the documents they leaked were initially published on a website whose IP address was tied (in the Muller campaigns recent indictment) back to a Russian intelligence front.

None of this justifies depriving him of due process, and going mad in isolation may have convinced him Trump’s election would’ve set him free, but it isn’t exculpatory. He was at best a tool of a Russian counterintelligence campaign, at worst a willing agent. He hasn’t taken responsibilty for the best case, and it wouldn’t surprise me if it’s something resembling the worst. He wanted to see the system burn to the ground, and by God he’s getting what he wanted.

or did Assange see the behaviour revealed in the emails, and without fear or favour expose it. Perhaps he thought less brave journalists would do the work on Trump… the information was in the public domain & in the public interest after all

Thanks Scott – articles like this make me re-consider my decision to cancel my subscription to Crikey.

Yes

Why on earth were you considering cancelling your subscription. ?? Crikey is such good value. !!

Brilliant article, made me think !!!