I haven’t been to the dentist in over a year. The reason is not just the pain of the drill but the pain of the bill.

I’m not the only one skipping the dentist; The Grattan Institute says 2 million people are not getting the care they need because of the cost. The effect is highest on people who are already disadvantaged.

But now a major report is proposing we change all that. The Grattan Institute is arguing for bringing in a Medicare-style universal insurance scheme for primary dental care which could make visiting the dentist possible for more Australians.

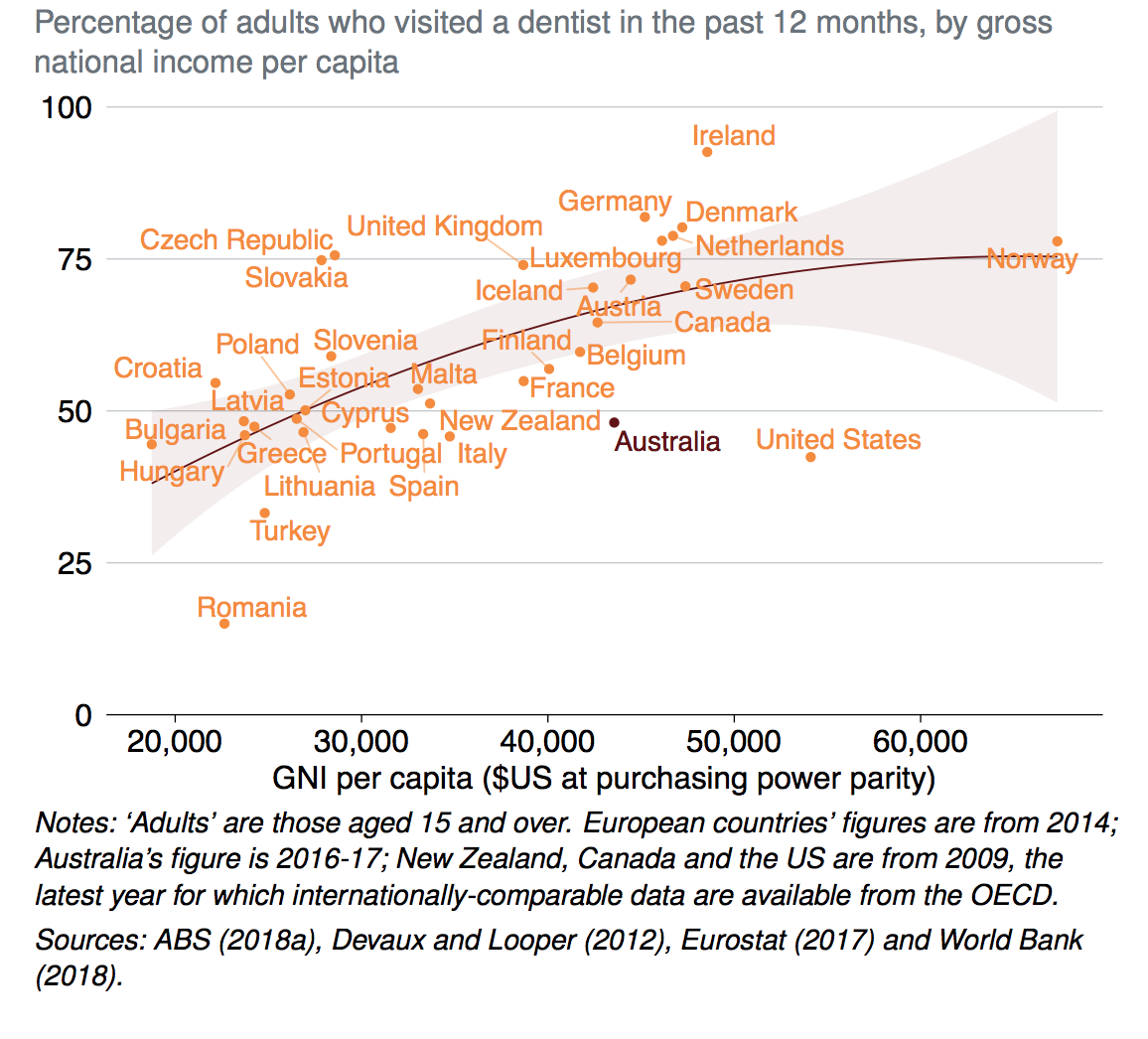

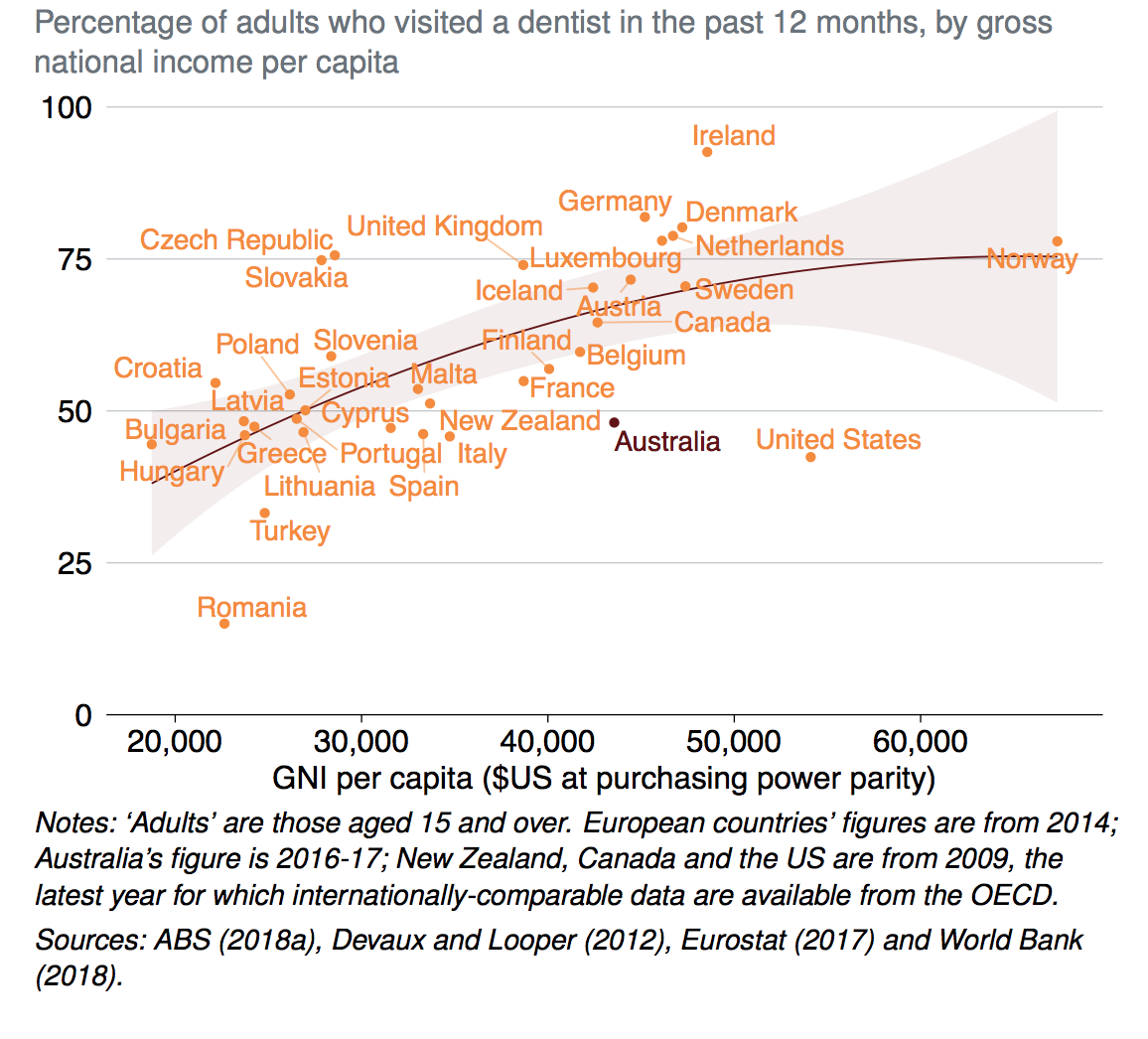

Australians, the Grattan Institute says, visit the dentist relatively rarely for such a wealthy country.

-

Source: Grattan Institute

A shortfall of dental care leads to greater health problems. We now have greater understanding of how oral health and body health interact. Diabetes in particular has a “two-way” relationship with oral health. Inflammation of the gums — known as periodontitis — can make the symptoms of diabetes worse, and having periodontitis is a risk factor for getting diabetes. Poor oral health is also linked to poor heart health.

Making dentist visits government-supported would remove one of the major impediments and be an investment in the overall health of all Australians.

Why separate dentists from doctors?

It may have been this somewhat barbaric history of dentistry that impeded its ability to merge with medicine. Modern dentists and barbers have their origins in a common profession — the “barber surgeon” — a sort of jack of all trades when it came to the human body. In pre-modern times much of the work of a barber surgeon was haircuts, bloodletting, amputations and teeth-pulling.

The history of barber surgeons is long. In 1540, Henry VIII merged the surgeons and barbers guilds into one and they remained as one profession for centuries. Some barbers continued to pull teeth into the 20th century.

In 1840 two dentists approached the medical school at the University of Maryland to ask about adding a dentistry course to the syllabus there and the doctors sent them packing. Dentists refer to this event as “the historic rebuff”, and the two professions have stayed as separate since.

A big cost to swallow

The cost of making government-funded dental care universal is an estimated $5.6 billion a year when the scheme is fully running. It would be a fraction of our federal health budget of around $100 billion. But that’s not to say the government will come up with the money easily.

A sum of $5.6 billion a year is almost as much as the government makes from taxes on alcoholic beverages, less than half of what it makes from taxes on tobacco, or about 10% of GST receipts.

So raising $5.6 billion may not be impossible but it would certainly be enough to tip a budget surplus to deficit. (Next year’s surplus is forecast at $2.2 billion.) The cost is just enough to make funding dental visits a hard choice.

What’s more, the cost of a dental scheme would be ongoing, in bad times and good. Politicians might prefer one-off spends like infrastructure that create less long-term fiscal commitment, and citizens might prefer other spending too — full funding of the NDIS or more money for schools. Just because spending is logical — and funding dental is nothing if not logical — doesn’t make it a priority.

But funds will always be limited and we must still always make tough choices.

The answer should always be yes. It’s a farce that in the 21st century there are people who are avoiding the dentist due to cost.

I think a worthy question that needs asking is what is the cost on the economy of people ignoring their dental health and eventually ending up in the emergency room as they let a small tooth ache cascade into something so much worse?

Exactly.

intellectually, it’s crazy that this one area of health is excluded from public health care and often health insurance due to accident of history. Financially, the way to making it work needs to be to make a case for how much money will be saved by preventative dental health care, and to work out ways for the cost of dental checkups to be reduced (given that dentists will be receiving a bonanza of more regular visits if such a plan was to proceed, they should not be able to complain much if there is a reduced fee for checkups compared to what they can charge now).

Do we actually have enough dentists to cope if that happens? That’s the other thing.

“…intellectually…” a concept which rarely enters into political, financial or religious debate.

Intellect appears to be a much denegrated faculty in these matters and others of a like kind.

Just precisely why dental health was not included in the Whitlam universal health model will always remain a mystery.

Certainly logic did not enter into the debate.

But then neither did the “Dismissal”.

With Whitlam it was partly for cost and partly for difficulty (sources vary on the difficulty), and it was more important to bed down Medicare for the rest of health care than to get dentistry shoved into it too.

I can think of 3 significant literary figures in 20thC Britain who died of dental abscesses prior to the introduction of the NHS.

As well as a couple of scientists.

Perhaps one way of funding it is to put a 100% tax on sugared and non-sugared soft drinks? Sugared drinks are a major cause of dental decay. Acidic carbonated drinks too (not including sugar doesn’t prevent them causing dental decay – my dentist warned me off them years ago).

Not having enough dentists and dental therapists might be a problem. I go twice a year for a checkup and to have the plaque scrapped off.

1. There’s an oversupply of dentists in Australia currently. It’s been that way for several years and it’s getting worse.

2. One of the consequences is a segmenting of the market: a proliferation of low-cost practices, with the survival of some practices doing the right thing with respect to diagnosis and infection control (and provision of what a lot of patients believe is unnecessary, like ‘choice’, or ‘keeping their teeth’) at the higher end of fee scales. The middle is being hollowed out by this market force, and corporatisation. As a result, in fact, dental fees are low and getting lower-as long as you’re happy with Coles/Woolies/Aldi type care.

3. The one thing that makes populations have better dental care isn’t more dentistry-it’s public health initiatives. Try this quick quiz: did you floss this morning? Statistically, you probably didn’t.

I’m old – 75++

I have most of my teeth still in place.

Those which have been removed were extracted before I turned 18 – mainly due to a diet of overcooked foods lacking in fresh vegetables and fruit.

Since then, an improved diet and a habit of flossing and thoroughly brushing last thing before bed each evening has resulted in only minimal dental visits – mainly as a consequence of physical damage incurred in my early life.

No need for morning flossing nor brushing nor the overstated brushing after every meal.

Avoiding continual exposure to sugars and acids in ‘soft’ drinks and snacks seems to be an essential component of good oral hygiene.

My last visit to a dentist was in 2001 to remove a tooth cracked in my youth by using it to open hazelnuts!

Tartar accumulation? What’s that??

“Tartar accumulation? What’s that??”

I think this is rhetorical, but, it always makes me laugh (like the economist who wrote this piece makes me laugh).

One of the best ways to not have dental problems is, to not see a dentist.

How can you have periodontal disease (or even calculus/tartar?) if it doesn’t hurt and/or you don’t see it. (I do mean you, because dentists see it).

What happened to my post? It disappeared. I can’t be bothered putting it in again.

I hope you have a change of heart totaram, as your contributions (as far as I can recall) are quite worthy and I often find the comments more informative than the articles.

The ADA is a much more fearsome outfit than the AMA, who are absolute sookie la la’s in comparison.

At the merest suggestion of including dental care in Medicare the ADA will have been in to the relevant Minister’s office.

“Minister, no change or all public dentistry in Australia ceases tomorrow” And the end result is no change.

Um…they didn’t, actually.

Wasn’t it the AMA who objected to dentistry being considered initially?

“DENTISTS AREN’T REAL DOCTORS AND SHOULDN’T BE ALLOWED TO CALL THEMSELVES DOCTOR!” – several medical doctors I’ve known when the subject of dentistry has come up

Except in Italy where a medical degree is a pre-requirement to study dentistry.

Have a look at the AHPRA website: ‘doctor’ is no longer protected (if it ever was) and any one can use it, even a chiropractor.

Arky…strictly speaking medical ‘doctors’ don’t have the right to call themselves doctor. Very few have a Phd in medicine.

So by custom, yes…but academically speaking, no.

Pot/kettle comes to mind!

Otherwise…of course dentistry should be covered by Medicare…even if we have to pay a slightly higher Medicare levy. And then there are all those people (me included) who are covered under private health insurance extras. Has this been taken into account when calculating the total cost of $5.6 billion?

No brainer that dental health care should be part of overall universal health provision. There does need to be some careful monitoring of a universal scheme however. The last time it was tried, the rorting by some generalist dentists, dental specialists and patients was bad and pervasive in some areas. That said, as has already been noted many times, a healthy mouth and teeth are part of essential health care. My partner had to have heart valve replacements because of horribly neglected teeth in his early childhood and youth with very bad dental heath resulting infections and damage to his heart valves.