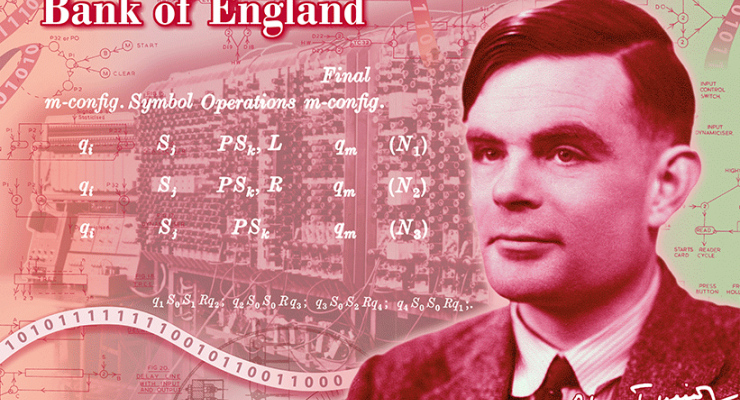

It’s a measure of the age that every new announcement that something has been decided raises not the question “is it good or bad?” but “why should we do it that way at all?”. Thus the decision to put computer scientist Alan Turing on the new UK £50 note comes at a time when one starts to ask why famous figures should be on banknotes at all.

Some will groan at this, for Turing’s selection — from a short list of 12 UK scientific figures, chosen from more than 200,000 public suggestions — is surely not only due to his crucial work in WWII, but to the fact that, though not “out” in his time, he is known to us as a gay man, and one who was prosecuted and persecuted for his sexuality.

Quite probably Turing deserves it for his grand historical role — no one else on the shortlist, apart from James Clerk Maxwell competes — though it seems ridiculous not to keep choosing women until parity is reached. Still, if anyone deserves recognition in this increasingly arbitrary exercise, it’s Turing. Most importantly, however, the selection of Turing furthers an intertwined set of new myths about the 20th century, the war and how we came to be who we are.

By now, a lot more is known about Alan Turing than was the case even a decade ago. Bletchley Park — the code-breaking centre he more or less ran, having been a classified secret until the 1970s — is now as much a feature of our imagination of WWII as the Battle of Britain or D-Day.

The short crib: in the ’30s, the Poles had passed on to the UK a captured “Enigma” machine, which used multiple randomisers (circuits, rotors, plugboards) to create non-repeating encryption, uncrackable by humans in real time. Turing’s research, following from Godel’s incompleteness theorem, theorised the inner logic of the modern computer, making possible first the pre-computer crackers – called bombes, due to their noise – and then “Colossus”, built by Turing’s chief engineer Tommy Flowers. Colossus was the first programmable machine, which got message decryption time down to six hours, thus allowing the UK and US to track German unit movements before D-Day, and to the end of the war.

Turing’s genius was not simply in the maths. He was a talented leader of large teams, a great talent-spotter, and self-assured in dealing with generals and prime ministers. When his full role became known once more in the 1980s, it was his fusion of pure maths and machines that was uppermost.

But then, as society and culture changed, so, for us, did Turing. He died of cyanide poisoning in 1954, two years after he admitted to having a sexual relationship with a man. The sentence offered to avoid jail was temporary chemical cessation of the sex drive, which he took. His subsequent death was ruled a suicide, as the poison was dusted on an apple.

By the 2000s Turing’s reputation had grown, as Bletchley’s role in the war was first recognised and then exaggerated. In a post-manufacturing information era, the idea of WWII as mass action was superseded by the knowledge class placing itself at the centre of the action. Turing became the predecessor of Steve Jobs, the smart solution to Nazism.

This culminated in the film The Imitation Game, a farrago of misinformation in which the entire war was observed, won and run from Bletchley. In so doing, the myth excluded the collective nature of the effort, such as the women staff, many of whom were proto-programmers on the bombes, and in particular Flowers, the designer-engineer of the Colossus, who appears to have developed full programming and “clocking”, the regulation of a computer’s action as discrete moments.

Flowers was a working-class boy apprenticed to telephone systems at the Post Office, so was always the most likely to be excluded from the story. But the most amazing twist in the film and the culture is to turn Turing into something he never was: the clichéd sad homosexual defined by his oppression.

Thus, in The Imitation Game, Turing is portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch as more delicate and Bloomsburyish than he was (he was remembered as brusque, no-nonsense and with little interest in the arts), his mathematical career defined by an attempt to “decode” a repressive society, all stemming from the early death of a schoolboy friend/love, Christopher, and Turing’s alleged exclusion from mourning him. In one ghastly self-parodic scene, Turing, now at Manchester University, has built his own computer in his shabby flat and named it Christopher. Death by poisoned apple soon follows.

What’s truly bizarre is that the culture is so desperate to make Turing over as a victim, the classic “doomed homosexual”, whose sexuality defines his whole being, that it subsumes his autonomous achievements in multiple fields, his ability to command, his clear-eyed view of the meaning of the war. Indeed, if anything, Turing was, in the common parlance, queer. He liked the secret gay bars of Washington DC, but he was also engaged and made an attempt at consciously turning his desire towards women, so as to have a family.

His death was most likely not suicide at all. The punitive chemical “castration” was over — he joked in a letter that it had freed him from distraction — and he was absorbed in the maths of the recently discovered DNA. He’d left computers, named and otherwise, behind. He did, however, dabble in electronics for which he made cyanide — useful in working metal circuits. On his death, he was found with traces of the highly lethal chemical on fingers and face. The 1954 coroner’s inquest deemed this suicide, simply completing the state’s view of a homosexual man as a tragedy.

That in turn has been picked up by a culture and class determined to put gender/sexuality identity at the centre of the modern struggle. As we put people like Turing on the money, we owe it to do so on their terms, and recall that despite all, it was the Western infantry and the Red Army wot paid the price.

Nice work Guy. I don’t know who the other contenders were for the cash pic but Turing and Maxwell are giants in modern science history.

I’m not one to defend or excuse the tedious conformity of gender warriors but you can’t really hang Turing as victim all on a Hollywood flick. It may be art but it’s mainly a commercial venture. I think most of us are still pretty sure it was real soldiers fought the war.

Turing was a victim of foolish laws and who knows what else he may have achieved had he lived longer. As you point out though he wasn’t the cariacature simpering poof.

“Real soldiers”: unfairly diminishes the role of the Enigma crackers, the encryption de-coders and code breakers especially including the women at Bletchley Park among others. It is akin to the military giving all the medals to the officers, despite them being at the (metaphorical) golf course while the crucial battle raged. Chiefs and Indians both play crucial roles; specialists and generalists also. The women who operated farms and factory processing all play a part.

Turing was hounded after the war for his sexuality according to history. It was appalling treatment, again according to history books consumed over the years.

This unintentionally takes me to mentioning the absorbing biographic “Between Silk and Cyanide” from Leo Marks one of the code breakers of WW2, one of the many books flooding bio- history shelves since the extra long embargo on WW2 documents expired recently.

Great history clarification. Thanks for this piece.

Finally, Tommy Flowers gets a mention. Everyone remembers Turing, but no one talks about Flowers, the bloke who took the computer to the next level.

Perhaps we should also mention those dedicated public servants who hid Turing’s and Flowers work away for decades under the Official Secrets Act and stopped proud, gentille, traditional England from becoming a crass and boorish computer superpower like those overpaid Americans in Silicon Valley.

Israel Folau would not be happy with this. According to him Turing would be in hell and definitely undeserving of such an honour. The fact that Turing was super smart, and a war hero would make no difference to Folau, according to his stated beliefs. He’d be classified as a sinner.

Annalise

Fascinating read.