Any kid who grew up in Mackay in the 1980s will remember the cane fires. They were in the late afternoon, usually. Spectacular roaring infernos, sometimes right next to suburban blocks where the streets filled with children trying to catch slivers of ash that fell from the sky like black snow. Mothers raced into backyards to strip clean washing off the clothesline. The rhythm of local life was set to the sugar season, planned around busy harvest months or “the slack”.

Things have changed a bit since then. Farmers don’t routinely burn the crop, for a start — harvesting green is more common. The town itself has become more of a high-vis hub for the booming coal mines in the Galilee Basin to the west. And the canefields that used to grow right at its doorstep have been replaced with “Cuttersfield Estate” — a residential development, full of four-bed-two-bath-two-car kit-homes forming a patchwork of Colorbond fences and fluffy turf lawns.

The land squeeze is just one of a number of challenges facing the Australian sugar industry. Growers are also unhappy about the recent introduction of “reef regulations”, which they say unfairly target and burden farmers with rules designed to protect the Great Barrier Reef. (The scientific community, by and large, disagrees. A Scientific Consensus Statement issued in 2017 stated “the main source of the primary pollutants (nutrients, fine sediments and pesticides) from Great Barrier Reef catchments is diffuse source pollution from agriculture”.) On the PR front, the “war on sugar” — and periodic calls for a sugar tax — has left many farmers feeling defensive about their crop, which has been grown here since before federation.

It’s a heritage that runs deep. With its own bulk port, refinery, and several mills, Mackay for a long time claimed to be the “sugaropolis” of Australia’s sugar industry (95% of national production is in Queensland, with a small amount of sugar cane grown in northern New South Wales). For 140 years, the city’s fortunes were tied up with the market for sucrose: a molecule so treasured by the human tongue that literal wars have been fought over it. Sugar growers and their families, many of them post-war migrants from Italy and Malta, have historically made up much of the social fabric of the region. But as the economic reality of turning a buck out of sugar hardens, the number of cane farmers is shrinking, even as the total amount of sugar produced increases.

The latest example of how this region’s central identity and way of life is changing, after a long history built around sugar, came with the recent sale of Mackay Sugar — one of the country’s largest and last-remaining grower-owned sugar milling companies. A deal finalised late last month has saved the mill from its crippling debt, and means Europe’s second-biggest sugar producer, Nordzucker AG, now has a majority stake in Australia’s second-biggest sugar producer.

Similar shifts are happening across the industry — there were once hundreds of sugar mills in the country; there are now 24. Much of that shrinkage is the result of 19th century tin-shed operations making way for bigger regional mills, but in the last 30 years, about a dozen mills have either closed or been sold to foreign companies. If a recently announced proposal for Pakistan’s Almoiz Group to take a 54% stake in Bundaberg’s Isis mill goes ahead, it will take the number of wholly- or majority-foreign-owned mills in the country to 19.

These acquisitions are keeping Australia’s sugar industry viable, but they are sometimes tinged with sadness. Paul Schembri, chairman of Canegrowers Queensland, described the Mackay Sugar sale as the end of an era.

“We need to be candid, there is a sense of mourning, the loss of 70% of equity of the company that was part of the heritage of our fathers and grandfathers,” he told the ABC.

Beginnings

Sugar cane is a robust crop requiring decent rain and plenty of sunshine to thrive. It’s very well-suited, in other words, to the “wet tropics” — but its establishment in Queensland was less to do with climate and more thanks to a colonial government anxious to ensure the “settlement of tropical and semi-tropical areas by a white population”.

By the early 20th century, official policy explicitly aimed to encourage European settlers into the continent’s northern regions, over concerns that “so long as these areas are unoccupied they are open to invasion”.

As a result, early plantations gave way to small farms, the government loaned money to establish cooperative mills, and most of the tens of thousands of South Sea Islander labourers (known as “Kanakas”) who’d been blackbirded in the decades prior to help cut cane were sent back to their homelands — even those who were born here, some of them second generation.

The policy also meant the government protected the sugar price, and ensured high wages for workers in the industry. Queensland’s Labor premier TJ Ryan, elected in 1915, took the view that “farmers were entitled to a ‘fair’ profit in the same way that workers were entitled to a ‘fair wage’”. For decades, having a cane farm was something akin to a golden ticket — albeit one that required back-breaking dawn-to-dusk work, in air so hot and humid it was like wading through thick soup.

Even with the cushioning of government support, sugar was always a boom-and-bust industry. At one point in the early ’60s, the world sugar price rocketed from $49 to $262 per ton in less than two years — paydirt for the 9500 Australian growers producing almost 12 million tons of cane annually. But just three years later, it had plummeted to $29 per ton– less than half of what it was costing farmers to produce at the time. That sort of financial whiplash has been a common experience over the decades, but it’s getting harder for farmers to absorb the shocks.

Industry protection ended with a long sweep of deregulation that began in the 1990s and finished in 2004, leaving Australian cane farmers more exposed to the vagaries of the world market. It’s a vulnerability currently being keenly felt — India’s decision to subsidise its own exports has driven down the global price of the commodity so steeply that at the time of writing, Australian sugar farmers are again getting less for their cane than it costs them to produce. (Along with Brazil and Guatemala — two other major sugar producing nations — Australia has asked the World Trade Organisation’s dispute settlement panel to investigate India’s subsidies. It recently agreed, but any resolution is likely months away.)

Productivity gains made through mechanisation and technological innovations mean that today, fewer than half as many farmers (around 4000) grow three times as much cane (35 million tonnes a year) as their forebears did 50 years ago. It’s unlikely that the next 50 years will see similar growth in output, but what is certain is the number of farmers will continue to drop.

The sweet life

William “Billy” Hobbs, 73 and still working, is a third-generation cane farmer in Gargett, about 50km west of Mackay. He might be the last in his family, ending a tradition that began when his grandfather, William Henry Hobbs, arrived here in 1906 with one-and-a-half sovereigns in his pocket.

“We’ve got replica of those coins sitting upstairs,” Billy says. “My father got them as a reminder of our humble beginnings.”

A century and a bit later, a two-story brick house sits on a small rise a few hundred metres from the original Hobbs home. It offers a 360-degree view of the 800 acres of cane growing at the foot of misty blue mountains. Billy’s grandfather’s hand-cut 400-tonne plot is now a 30,000 tonne operation. A hangar-sized shed houses the millions of dollars worth of machinery it takes to grow and harvest the sugar cane — but it’s still not big enough to make it worth Billy’s son taking it on.

“50 years ago, growing 2000 tonnes was a comfortable living,” Billy explains. “Today, 20,000 tonnes isn’t enough. And in another 50 years, you’re going to need to grow 100,000 tonnes to make [ends meet].”

“The only future for this industry is big companies,” Billy says. “Family farms will all but disappear. It’ll come to last man standing. It’s sad for me — I see a lot of young people leaving the land. They’ve got no option.”

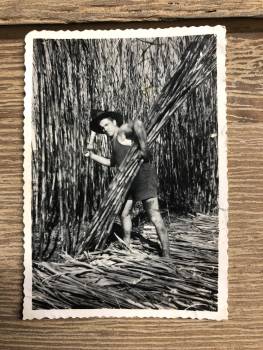

Silvestro “Sib” Giumelli, 86, has a similar story. Born here in 1933 to one of the first Italian families in the region, he can remember when his mother cut the cane and his father lugged it all to the tram line for the mill.

“We only grew about 300 tonne,” he says, “you could do anything with a few hundred tonne then.” Now, the Giumellis average 6000-7000 tonnes a year. Sib’s son, Walter, helps him with the harvesting and planting but is mostly kept occupied with his own earthmoving business. There’s no one lining up to take the 200 acre property on once they’ve both had enough. Sib thinks it’ll just “peter out” — that the house and surrounds will stay in the family, but other parts of the farm might be sold off to neighbours looking to increase their own production.

Bigger farms, fewer farmers. That’s the future of Australian sugar.

The thing is, upscaling isn’t so straightforward.

Good land is hard to buy

Many of the region’s smaller farms, on prime agricultural soil, are being turned into lifestyle blocks. Miners, cashed-up from jobs on the coal pits a few hours drive away, can pay a higher price than most farmers can afford. So instead of being consolidated into the surrounding properties, these blocks are often carved up into housing estates or hobby-farm acreages.

“You can see it happening everywhere,” Sib says, “all the good farms at Pleystowe were subdivided. It’s all housing now.” Pleystowe, a locality that stretched along the Pioneer River, was once home to Australia’s oldest operating sugar mill. But development, blamed on the mining boom, chewed up the “cane country” that fed it.

Farmers who want to go bigger need to pay a premium for proximity, or are pushed further out onto suboptimal land. There’s nothing stopping this trend — which is a problem across the agricultural sector — from continuing. Australia does not have a policy or plan to protect arable land from being commandeered for other purposes, the way many other countries do.

Brett Simpson, 26, considers himself one of the lucky ones. He’s been able to buy a 65-hectare block just down the road from his father’s 200-hectare property, making him the fourth-generation member of the family to go into sugar.

Brett’s father Wayne, 58, bought the main property off his father Mervyn, 87, in 2004. All three men still work on it, although Brett, a diesel fitter, currently works “off-farm” as a diesel mechanic four days a week, too. Working two jobs is tough, but it’s the only way he can pay off his debt.

“I’d much rather be at home, on the farm,” he says, “but that’s the only reason — to pay it [the farm] off and make it work, and get it to the point where it’s enough to be full time.” Ultimately, he aims to consolidate the properties and grow 800 acres himself.

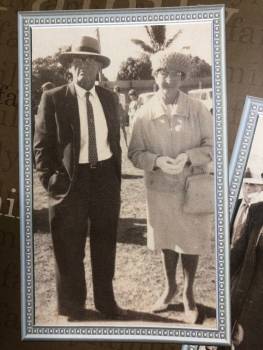

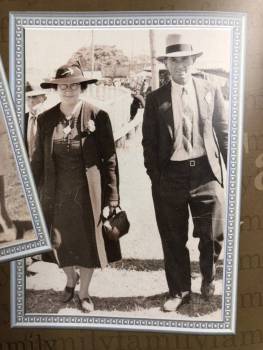

We sit around a glass-topped table under the house Merv was born in. Merv’s wife of 63 years, Audrey, brings out the family albums and a handful of black-and-white photographs of the property in the 1950s, not long after Merv took it over from his father. The pictures show Merv and Italian labourers loading a tractor with bundles of fresh-cut cane.

The Italians — and the Maltese who followed soon after — were on the hunt for a better life after the war ravaged Europe. Many ended up farmers themselves, spawning local sugar dynasties from Bundaberg to the Burdekin. The Muscats and Borgs, the Sammuts and Zammits, the Vellas and Vassallos and Bugejas and Camilleris — they all helped create sugar’s multicultural legacy. For those families, too, succession plans are getting trickier.

Of course, the other looming challenge is climate change — a topic hard to broach in Adani-land. Farmers have lived forever with “predictably unpredictable” weather — wet seasons that are sometimes wetter than normal, dry seasons that occasionally test their patience and devastating weather events that can ruin a whole season’s hard work. This is already cyclone country. And yet, no one INQ spoke to was especially concerned by climate projections for the region — linked to various greenhouse gas scenarios — which show a widening spectrum of expected rainfall and rising temperatures. Merv Simpson said he didn’t think it was any hotter now than it was when he was working in the fields in the ’60s, when the sun was so scorching it felt like his shirt was on fire. Sib Giumelli brought the issue up while talking about how highly he rated Andrew Bolt, Paul Murray and Alan Jones, who call it out as nonsense. Brett Simpson said he viewed it as a “slight concern”, but figured weather has always been the factor out of farmers’ control.

However the way the industry deals with these environmental and economic challenges will have consequences for the wider community. More than one in ten people in the Mackay region still have jobs that rely on sugar, which generates 17% of the town’s gross regional product. Like many of the other cane towns dotted along the Queensland coast, life is still largely defined by the white steam billowing out of the mill stacks, the clatter of cane trains at level crossings and the rank smell of dunder wafting across town when the wind blows the wrong way.

So cane farmers are human beings?

So were tobacco farmers, car workers etc.

Thank you for this look into the history of sugar in north Queensland. Our colonial history is not as far away from us as we would sometimes like to believe. It would be awesome if INQ could do more stories on that part of the world.

White Australia Policy, dispossession of indigenous people, slavery, this story has everything. And speaking as a fourth generation farmer, even now the romance of the family farm and its somehow morally superior inhabitants continues to wreak political and environmental havoc.