Central Station Records has done it again. The record label behind this week’s No. 1 ARIA single has a storied place in our cultural history: after a David and Goliath legal fight against the record label establishment and Rupert Murdoch, it changed the face of music.

Now the dance and hip hop label is back on top more than 40 years after it was founded. Its latest success, a remix of “Roses” by the US rapper SAINt JHN, regained the No. 1 spot on the ARIA singles chart this week having slipped to No. 2 after two previous weeks on top.

“It’s a wonderful feeling,” says Morgan Williams, 68, who owns Central Station Records with his partner, Giuseppe Palumbo, 70.

“Once upon a time you’d make a lot of money out of [a] No. 1 single. These days there’s not the money in it that there used to be, but the feeling doesn’t change.”

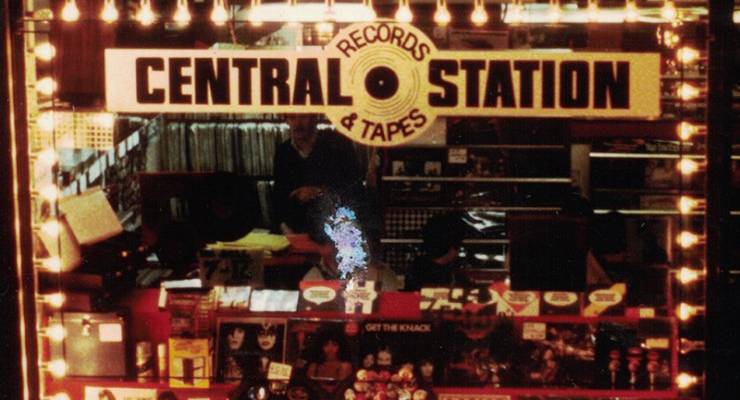

The couple met late one evening in Melbourne in 1982. At the end of the ’70s Palumbo had bought a tiny record shop in an old arcade opposite Flinders Street Station and founded Central Station Records & Tapes.

In many ways the story of Central Station is the story of our popular culture, from importing disco, dance and hip hop music into Australia when the major labels weren’t interested, through to the legal fights in the 1980s over record imports, continuing past the dance music boom of the ’90s and into our near future of virtual reality, ethical manufacturing and environmental remediation.

“Kids don’t follow music they way they used to,” says Palumbo. “The way they used Central Station was to provide a place. Now clothing is doing that.”

But Central Station is mining a rich vein with its back catalogue. “We are putting out compilations of our classic hits,” Williams says, with a somewhat different definition of the term. “The kids are enjoying stuff from the ’80s.”

Those “classics” include such hits as the seminal 1988 hip hop album Straight Out of the Jungle, by the Jungle Brothers, while in the ’90s the label rode a wave of success with tracks such as “Here’s Johnny” and a remix of “Total Eclipse of the Heart” by Nikki French.

Today the couple see positives and negatives in the dominance of streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music.

“We are very happy that the music is delivered by streaming services, that’s the future for us,” Palumbo says.

Once a single 12-inch single would cost $15; now that is the monthly fee for a streaming service. “They have got more money to spend on sneakers and clothes,” Williams says.

But both acknowledge streaming has cut the earning capacity of artists and labels, but made distribution so much easier.

When Palumbo started up he began importing records shunned by the major labels and DJs queued to buy the 12-inch rarities — which they had read about in Billboard magazine — at inflated prices. Later shops were opened in Sydney, Brisbane and Adelaide.

For decades the “big six” record labels, including Festival Records — then owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Ltd — jealously guarded laws that stopped anyone importing music from overseas without a licence. It was a restraint of free trade known as a ban on parallel imports.

The law stymied attempts by Central Station to import dance music records, music the big labels weren’t interested in. After legal battles the law prohibiting imports was changed in 1998.

“That changed music — dance and hip hop became more than 30% of market,” Palumbo says. It also brought down the price of CDs.

But the famous victory was ultimately a pyrrhic one.

“Parallel importing doesn’t mean jack shit,” Williams says now.

“Spotify and others cleared all that out. Piracy has all but disappeared,” says Palumbo. “You can get everything on YouTube.”

The couple’s unlikely story is told in a book, Music Wars: The Sound of the Underground, which on the verge of becoming a TV mini-series.

The romance of lugging bags of CDs and tapes to music stations and listening on international phone lines to Euro dance hits has given way to the next big thing. Central Station Records has launched a partnership with NextVR to broadcast immersive virtual reality streaming of epic nightclub and DJ sets from the biggest dance events globally.

“It is all about entertainment,” Williams says. “It is all about glueing the poor buggers to their phones even more than they are now.

“Ethically I am opposed to it, but from a business perspective that’s where kids are getting their entertainment from.”

Today the pair are semi-retired and play a tangential role after installing partners and managers in their investment, property, music and retail interests, which import brands including Stussy, Acronym and Carhartt.

They divide their time between their Kings Cross apartment, complete with Roman columns and a grand piano, and their properties on the Sunshine Coast hinterland. Two passion projects are the environmental remediation of land and the ethical supplies of products, particularly in the fashion industry.

“It is interesting to be at the leading edge of youth culture,” Williams says. “I downloaded TikTok three years ago, when it was Musical.ly, because the kids in the shop were using it. We are just curious individuals.”

Palumbo says: “I just like to be part of the development of ideas.”

Central Station Records was a teenage pilgrimage for me and my friends. We would make a day trip by train from regional NSW to the alternative record shops.