While the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has methodically exposed major and often systemic flaws in administration within the public service, there’s been a growing bureaucratic resistance to its scrutiny.

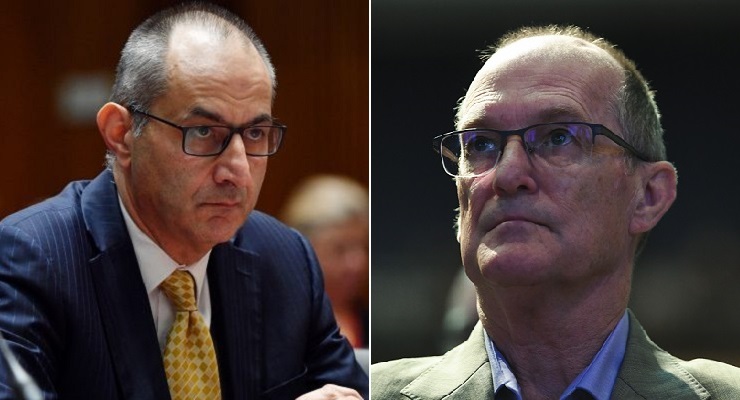

The resistance has been led by one of the public service’s most senior figures, Home Affairs secretary Mike Pezzullo, whose portfolio has been repeatedly humiliated by the exposure of major failings by the ANAO — some of them, like the botched handling of the return to offshore processing under Labor, well before his arrival in the job, but most subsequent.

Departments are asked to respond to audits and their recommendations; agreeing to recommendations represents, in effect, a commitment to parliament by the government that the recommended action will be undertaken. Despite Home Affairs, in its various iterations, agreeing to nearly all of the recommendations made by the ANAO in its string of scathing audits, Pezzullo has repeatedly attacked the ANAO.

When the ANAO discovered Australian Border Force had been abusing its powers, Pezzullo attacked the auditors as “unworldly” authors of a sub-standard report. Last year, Pezzullo mocked the ANAO’s recommendations for improved transparency and performance monitoring of his department’s citizenship applications as “cookie-cutter targets” that “drive poor behaviour”.

To spell out his displeasure, Pezzullo had a junior executive sign off on his department’s response to the ANAO. Pezzullo has also complained that his department is repeatedly singled out for critical ANAO attention in “a bit of a reoccurring pattern with the audit office”.

Pezzullo’s bureaucratic boss, former Liberal staffer and current Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) secretary Phil Gaetjens, didn’t deride the ANAO in his “review” of the sports rorts affair early this year but went to great lengths to discredit the ANAO’s forensic demonstration that Bridget McKenzie’s office directed the grants at targeted seats, devoting most of this statement to parliament to a series of thin and easily debunked arguments about how the ANAO got it wrong.

Sometimes agencies invent novel excuses for why they disagree. The Australian Electoral Commission recently claimed that parliament didn’t want it to use the full range of enforcement powers its legislation gave it, and the ANAO “misunderstands the intent of the legislation“.

Even when the Department of Infrastructure was caught red-handed paying 1000% more than it should have for the now-infamous Leppington Triangle land, it insisted the ridiculous valuation process it undertook, while “unorthodox”, was designed to discourage litigation — as though the Commonwealth should pre-emptively hand over taxpayer money out of concern than a billionaire will resort to litigation.

The ANAO, which has stepped up its monitoring of the implementation of its recommendations, noted that in its 2018-19 audits, it made 146 recommendations, 131 agreed by agencies, some of whom “respond to external criticism defensively or dismissively (‘we are already aware of the issue’, ‘we are already addressing the issue’, ‘the report needs to be read in context’, ‘the issues raised are not material’)”.

It also pointed out a tendency for agencies to evade action without formally disagreeing with recommendations. Some tried to “agree with qualification”, where the qualification in effect dismissed the recommendation. Others liked to “note” recommendations, which the audits described as “equivalent to disagreeing”.

But apart from media coverage, and the occasional stern letter from PM&C to departments about following through on audit recommendations, there’s little the ANAO can do beyond public shaming. The only real enforcement it has in relation to follow-up is provided by the Joint Committee on Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).

Under Liberal senator Dean Smith, from 2016-19 the JCPAA aggressively backed the ANAO, supporting Auditor-General Grant Hehir in his campaign to stop the same problems cropping up over and over in the Public Service. It was especially diligent on cybersecurity, following up the ANAO’s own efforts to monitor agencies’ failure to implement cybersecurity basics, but routinely initiated inquiries into major ANAO reports, or batches of them, to grill senior public servants.

The committee also upped its work rate from the previous parliament — under Smith, the committee managed 22 inquiries or reviews and had two more — including cybersecurity — going when the 2019 election was called.

Under new chair, NSW Liberal MP Lucy Wicks, the committee has only managed seven completed or current inquiries in the 12 months, half of them COVID-affected, since getting up and running after last year’s election. Tim Watts has been using the committee to pursue the cybersecurity issue but it is unlikely to match Smith’s time as chair for the pressure put on agencies — seemingly the only way they can be forced into action.

“Are you being served?”

By lawless bureaucrats hand-picked by a lawless government to work with/for that lawless government? Fat chance.

The situation has two sources: a culture that comes from the top and what they have got away with in the past.

But the ANAO expose only a fraction of the maladministration – because their auditors are often no match for the experienced people they are auditing. (And I write as an ex- one of the latter. We saw an audit as a competitive performance, a bit like a joust in a comic opera: we’d dance around them, they’d throw a punch our way, we’d pirouette on to the next exchange.)

Did you throw in an “attractive person” to distract auditors too? Something I came across quite often – they knew the weaknesses of some of ours, it was interesting to watch.

Yep KT – see Kathryn CAMPBELL’S rationalisation for impunity re illegality of “robodebt” based on “…what they got away with in the past”.

NO!

While Dutton is Home Affairs Minister, the Department is untouchable!

The Gestapotato is only the monkey, Pezzullo is the organ grinder.

This poor governance of our limited resources is bordering on corruption and at least paves the way for a full blown corrupt Government. It needs to be brought to a stop as soon as possible because it is becoming so commonplace that it is being accepted as a standard.

Change would require the electorate to vote accordingly but for whom?

“Labor” is not worth feeding and the Greens ‘ingenues R UZ’ are chained within the latte belt.

I won’t even mention those already at the trough.

Some of the greens are crazy, but have you actually read their policies. Grounded in science and logic. In other words, we should be using them

I’ve been a member since they were formed decades ago.

Which is why I’m underwhelmed.

Why are they so violently opposed to cooperating with Labor, where they could get an opportunity to see some of their initiatives actually implemented?

I think you have that the wrong way around – most Greens (even the absolutist crazies such as myself) would welcome an accommodation with “Labor”.

That was ruled out by Gillard in her last Party conference and constantly repeated by the braindead apparatchiks still running the party into the grave.

Please don’t swallow the nonsense about not backing Krudd’s ETS – they WERE NOT ASKED.

He thought Talcum would support what was a job cration scheme for merchant bankers & corrupt autocrats.

The rest is history.

The Kredlinator had the gall on 2GB last week to state that “Labor” could only win seats on Green preferences.

No mention that, apart from once after 1975, the Liberals would never be able to form government without the gNats’ gerrymandered seats.

We, the People, are not permitted to see the agreement that forms the basis of the COALition’s gravy train Ministerial allocations.

So, yes there should be a formal agreement between the dead husk of “Labor” and Greens but that will not be possible whilst the Gibbon/Charmless & Dreyfus pull the strings.

(AA is irrelevant – he doesn’t get out of bed without permission from SussexSt.)

Some bureaucrats and politicians forget who pays their generous wages. And one day they will be the victims of poor process and biased decisions.

Unless we accept that greed and corruption undermine our strengths as a nation we will end up with a small rich and large poor population. Who wants to live like they do in the U.S. and other distorted ‘democracies’ ?

There’s “pay (for work)” : and then there’s “donations” and, later, “post-parliamentary employment”.

It’s easy to forget the first in the face of the other two – “obviously”, going on the evidence?

It is really very hard to shame either Pezzullo or Gaetjens because neither of them have any ability to feel shame.