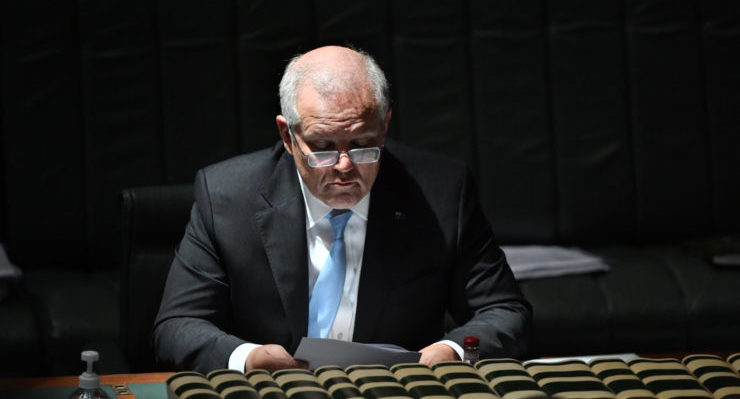

The consensus is that Scott Morrison has had a good pandemic — a policy and political success good enough to bury memories of his ill-judged holiday in Hawaii as bushfires scorched the nation. Which does seem an age ago.

But has the prime minister really done so well?

While his domestic response has been successful, major problems are emerging from his international response and they will have significant ramifications.

In April, Morrison took the international lead in demanding an investigation into the source of the coronavirus, even proposing independent investigators with powers like “weapons inspectors”.

This was clearly a diplomatic blunder of the first order. It infuriated the Chinese government and was the catalyst for a major deterioration in the Beijing/Canberra relationship.

There were already simmering tensions between the two over anti-foreign influence legislation, Huawei, the treatment of Uyghurs, Hong Kong, the South China Sea, and more. Against that background, who thought it would be a good idea for Australia to call for an invasive and comprehensive investigation into the country that buys 40% of our exports?

To be clear, a thorough investigation into the source of the virus is vital, and it would have been appropriate for Australia to be part of a coalition calling for one. But to lead that call was reckless. The title of a recent editorial in The Global Times, a mouthpiece for Beijing, conveys the depth of China’s anger: “China’s goodwill futile with evil Australia”.

We are already paying the economic price as China places obstacles to, and sanctions on, a growing range of Australian exports including beef, wine, lobster, coal, timber and barley. The potential downside for two of our major export earners — tourism and education — is frightening.

The damage to Australia’s economy will have political consequences for Morrison — from the impact of job losses to the challenge of the National Party demanding extensive compensation for the agricultural sectors targeted by China.

But his problems won’t be limited to the economy. China has shown it’s prepared to wreak reputational as well as economic damage. It has seized on the Brereton report into alleged war crimes committed by Australian troops in Afghanistan.

Beijing’s message is clear: it is hypocrisy for a country that commits war crimes to accuse China of human rights violations.

There is clearly no equivalence here but that won’t still the Chinese cry of double standards.

If, as seems likely, the Morrison government cannot repair the China relationship any time soon, we should expect to hear much more from China on the Afghan affair. Australia is also exposed to potential criticism for its offshore detention arrangements and for Indigenous disadvantage.

A Chinese accusation of inconsistency is another risk for Morrison. Beijing may argue that Australia is quick to condemn the treatment of the Uyghurs but is largely silent on the treatment of Muslims in India and of women in Saudi Arabia. Again, China won’t be silenced by charges of false equivalence.

Under sustained pressure from China, Australia must look for support from its allies. This may have some unforeseen domestic consequences for the Morrison government.

To maximise support from the likes of the UK, France and the United States, the government will need to minimise areas of disagreement with them. One such area stands out: climate change policy. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and French President Emmanuel Macron have legislated a net zero emissions target for 2050. The same target is a major policy of the incoming Biden administration in the US.

In the quid pro quo of international politics, it’s hard to imagine that Morrison won’t come under pressure to adopt a climate change policy more in tune with that of our major allies. The desire for their support in the quarrel with China may make resisting that pressure difficult.

Of course, there is nothing more dangerous for a Coalition prime minister than climate policy. No one knows that better than Morrison, a minister in both the Abbott and Turnbull governments. The usual cabal of coal champions and climate change contrarians will fiercely resist any movement on climate policy.

Any internal disagreement on the climate issue will probably reflect a wider conflict within the Coalition on how to handle the China crisis. Morrison will be caught between hardliners wanting to “shirtfront” the Chinese and moderates urging him to negotiate a reconciliation. In other words, business as usual for the Coalition — the conservatives versus the liberals.

To resolve that, Morrison will need all the diplomatic skills he’s so far failed to demonstrate in dealing with Beijing.

Could it be that Australia, rather than Morrison, has had a “good” pandemic because the States took on the task of coping? As the Premiers and their Chief Health Officers closed borders and Victoria instigated a complete lockdown in Melbourne, my memory of Morrison et al is of carping and unjust criticism that the borders were closed for too long. Daniel Andrews came in for fierce condemnation, but as noted in the “Arsehat/Person of the Year”, he fronted up to the media every day. There were no “thanks everyone” or “on water matters/ I’ve already dealt with that/ I don’t agree with the premise of your remarks” moments.

I’m glad that Morrison had the good sense to leave it to the States – a win-win for him. If they stuffed up, not his responsibility, if they didn’t, plenty of kudos for him. He seems to have dodged the bullet of the aged care crisis.

It was the States that were responsible for Morrison’s “good” pandemic. And, mostly in the face of much criticism from the Feds. As for age care, I think there is still some space there for further problems for Morrison.

China may well prove to be Scomos Waterloo as the rural sector turns on the rodents in the National Part and the Independents take a swag of seats from them .

Morrison may well hasten his Waterloo, Brian, if he chooses one particular cabinet reshuffle currently ‘rumoured’ to be on the table.

Birmingham’s vacating “Trade and Tourism”.

How do you reckon Michaela Cash would go dealing with the Chinamen?!

Personally, I reckon it would be hoot. But then, I don’t have to worry about finding or keeping employment, paying off any debt, or selling any products resulting from my labours

My hunch is that Trump put him up to it.

Trying to emulate the Rodent’s grovelling to Shrub to be Trump’s sheriff in the region.

The author used the old “equivalency” argument when comparing s single Australian HR failure to the HR claims of the west whereas they should have, as a minimum, compared our HR record in its entirety. Our 2019 report shows we are far from being able to claim “moral superiority”:

https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/australia

China has every right to claim “double standards”.

China’s attack is at best an example of the Tu Quoque fallacy.

Hardly. This is what you receive when you cease diplomacy and attack another sovereign nation repeatedly.

The author would also do well to do some background research.

If he did, he’d find there is an investigation into the origins of the virus, and the WHO has the cooperation of all but a handful of countries.

And, the WHO is building a timeline. One recent point added to the timeline can be found by looking around the interwebs for; ‘Italy coronavirus September’.

Italian medical researchers came up with an interesting scouting exercise to establish that the virus was in Italy in September.

From SBS;

“But the Italian researchers’ findings, published by the INT’s scientific magazine Tumori Journal, show that 11.6 per cent of 959 healthy volunteers enrolled in a lung cancer screening trial between September 2019 and March 2020, had developed coronavirus antibodies well before February.”

This was Morrisons equivalent of Abbott’s shirt fronting! Great for the backers at home but stupid in a diplomatic sense! Morrison is not a diplomat’s a-hole. Rather than working though the professionals he blew it! Whoever would have thought that China would single out Australia when Australia ( Smirky) stood out initially , friendless and poked the dragon in the eye.

Sure the WHO came on line eventually , but that was the agency to work with and through.

Considering that there were direct flights from Wuhan to Milan and Madrid 3 times a week which only stopped when the massive outbreak occurred in March 2020, it would not be surprising that Covid19 or a close relative was out and about in 2019.

It takes a while for a pandemic to really get rolling. Covid19 was known to have attended and then hitchhiked out of Singapore gas conference in November 2019.

One delegate took it back to Seattle with him, thus there were lots of community transmission with no retrospective PM numbers to work with.

Another took it from Singapore to skiing in France, being super-spreader he gave it to at least 15 people then, then onto London, where about 5 got it from him and then he got home to Brighton, where he gave it to his GP and another working in the same practice.

So, yes there is irrefutable evidence that Covid19 was present in small numbers in different countries. The majority of cases led back to contact with people from Wuhan.

Keeping in mind that the Ophthalmologist Li Wenliang who originally described Covid19 symptoms in patients and warned his colleagues in December 2019 indicates that it certainly active for a couple of months before that.

Good list.

However, I’m with the WHO person I saw, a coupla weeks back, who counselled against jumping early e.g. on “The majority of cases led back to contact with people from Wuhan”.

“Majority” is not “origin”. It may turn out to be the same place for both, but they have a long way to go.

It remains possible it was in Italy before September. The samples from the volunteers in the screening exercise only started being collected in September.

And, significant numbers of ‘excess deaths’ in ’19, in various places that were hit by the virus in ’20, remain to be explained.

Human rights is not at the core of this diplomatic debacle. It’s but 1 of the 14 issues tabled by the CCP, and so even if they could claim double standards, so what?

Who are the contenders claiming of and for this consensus ?.What happened to all the contestations ? That’s some real sleight of hand smoke n mirrors re-writings of realities for anyone or anything, to lay claim to Morrison having a good pandemic..Well maybe he personally had a good pandemic, but he was pretty bloody useless in dealing with it overall, if facts of the matter were examined .In fact he was downright deviously dodgy inept in all his cunning politiking dealings.Thank hell we had some better minds & hands across the country trying to guard the best health interests of Australia..

They were my thoughts on reading this article as well. Morrison lived off the hard work and achievement of others with this pandemic. He just showed up as Mr Stupid who would have caused us so many problems in managing the virus if the Premiers did not take a stand against his demands. He is Mr Cruel as well in our country with so many policies and actions against fellow human beings, especially refugees and the needy in our land, he has not the moral authority to call out China. We will get nowhere in our relationship with China whilst he and his merry men are in power

With you Raymonded. Morrison was shown to be the shallow fool he is. Alas, with Murdoch in power, he was held aloft by lots of hot air.

The States, eventually, had a good pandemic. They did make a batch of horrendous mistakes on the way though, and not just Victoria.