More types of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) will be funded through the Medicare Benefits Schedule as part of a $354 million package to support the health and well-being of Australia’s women.

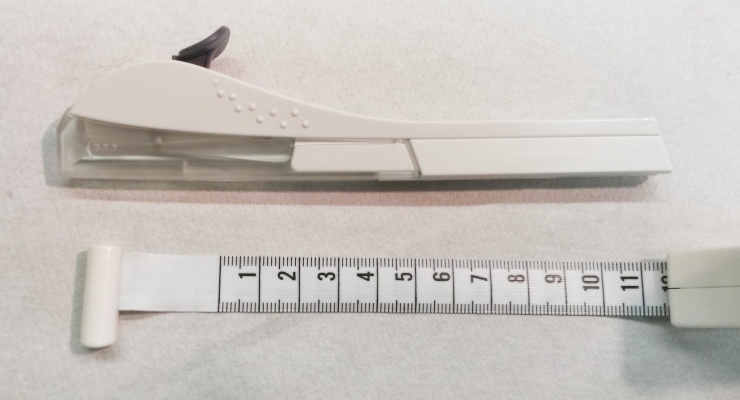

Australian women are behind the rest of the developed world when it comes to access to LARC, which consists of contraceptive injections, implants or the intrauterine device (IUD), and are more likely to pay for the expensive monthly doses of the combined oral contraceptive pill.

The new funding is unlikely to address the root cause of Australia’s low uptake: doctor bias, lack of information and limited incentives for doctors to learn how to insert LARC.

Cost and consultation a concern

LARCs are a “set and forget” method of contraception, lasting from months to years depending on the type, and they’re more effective than the pill. Women using the pill account for 39% of women aged 18-23 years old who reported an accidental pregnancy in Australia compared with 2.7% of women using LARC and 29.4% of women using condoms.

When a woman decides to go on contraception, she books a 15-minute consultation with a GP. Australia has one of the highest rates of women on the pill in the world, with 29% of women using it compared to 17% in other developed countries. Just 1.5% of Australians use an IUD compared with 14% worldwide.

Honorary professor in sexual health in the Kirby Institute Juliet Richters told Crikey the limited consult time was a huge concern.

“There are huge gaps with knowledge and mismatches of expectation of doctors and clients so that the doctor kind of assumes young women have done all her research of the alternatives,” she said.

GPs who have undergone training to insert LARCs were more likely to prescribe it, though there are limited financial incentives for them to undergo that training. It’s not clear whether this will be addressed in the latest budget package.

Another concern is GP bias: when IUDs were first released in the 1970s, poor designs meant they were linked to infertility, serious illness and death in women, which are not a concern with modern IUDs. Despite this, one study has found there is a “hangover” from outdated teaching, with doctors still believing IUDs are for women who have had pregnancies, and not for young women who were formerly at risk of infertility.

IUD companies reinforce this through advertising, Richters said, with ads featuring women with young children.

Price barriers challenging women’s choices

Many women on lower incomes are locked out of newer versions of the pill, which may have fewer side effects. During the pandemic, there were also supply shortages of some types of the pill in Australia, meaning many women had to fork out for brands not listed on the pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS). Since 1992, just one new contraceptive pill has been added to the PBS.

Chair of the Australian Women’s Health Network Bonney Corbin told Crikey this lack of access was a concern. “You want someone’s contraception choice to be influenced by their bodies and their personal desires and not by cost,” she said.

“There’s a lot of lobbying for no- or low-cost contraceptives because then you wouldn’t experience bias around price.”

More focus on choice

Importantly, LARC isn’t ideal for everyone. Some women feel they lose control of their bodies with LARC, Richters said, not least because if they start experiencing side effects they have to find a doctor willing to remove it.

Hormonal IUDs can also have side effects from irregular bleeding and heavy periods to cramping, headaches and nausea, while the pill is often prescribed to help with period regularity and acne. Neither protects from sexually transmitted diseases.

Investing in LARC insertion training for doctors, and providing incentives for them to take it up, while also increasing contraception literacy in school-aged children and adding more contraception options to the PBS, as planned, would allow women to have more choice and control over their bodies.

“GPs who have undergone training to insert LARCs were more likely to prescribe it, though there are limited financial incentives for them to undergo that training.”

I am a GP who is trained in the insertion of LARCs and I perform this for my patients. You are correct about lack of incentives for the training. Another obstacle is the Medicare benefit of only $55.20 for insertion of an IUD, which nowhere near covers the costs of the equipment, doctor’s time and nurse’s time.

“Importantly, LARC isn’t ideal for everyone. Some women feel they lose control of their bodies with LARC, Richters said, not least because if they start experiencing side effects they have to find a doctor willing to remove it.” Ideally the doctor who inserted it should be the one to remove it. Removal of IUDs is usually quick and easy and does not require any special training or equipment.

“Hormonal IUDs can also have side effects from irregular bleeding and heavy periods to cramping, headaches and nausea, while the pill is often prescribed to help with period regularity and acne.” This is incorrect. NON-hormonal IUDs (all of them using copper) can make periods heavier and more painful. Hormonal IUDs (Mirena and Kyleena) almost always make periods lighter and in most women suppress them completely after the first few weeks.

Contraceptive pills have multiple purposes – one is to stop conception, but women like my spouse take contraceptives to relieve symptoms of dysmenorrhea and other similar symptoms of the menstrual cycle. In the research and reporting,

It would be interesting to know the breakdown between women taking contraceptives to prevent excruciating pain on a monthly basis vs preventing pregnancy. This may help with better management of women’s health in general, not just controlling fertility, especially in stable relationships where a woman’s spouse is no longer “fertile”.

Development of long-term contraception for males might allow families to choose the sex of their babies, by suppressing only one of the X sperm and Y sperm.