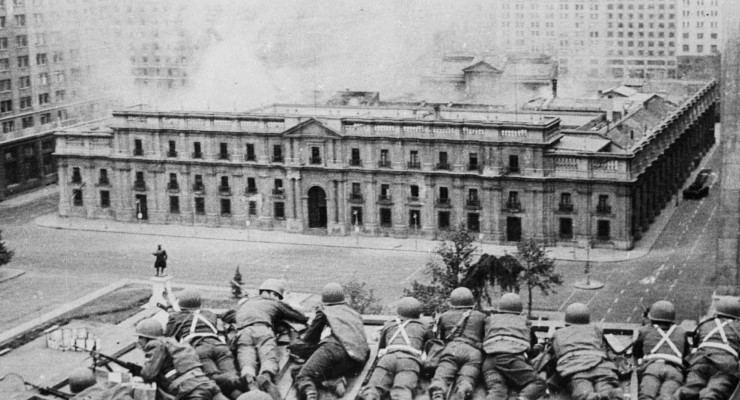

Bombs rained over Santiago, Chile, on September 11, 1973. That morning, after months of political chaos, the country’s military launched a coup. Holed up in La Moneda, the presidential palace, Salvador Allende, the country’s socialist president, recorded a final, defiant radio address to the country. Then he took his AK-47, a gift from Fidel Castro, and shot himself.

Chile’s coup introduced 17 years of repressive military dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet, in which thousands were killed, tortured or “disappeared”.

That dark moment in the nation’s history would never have happened without Western meddling. We know the United States was desperate to remove Allende, and that the CIA helped create the conditions for the coup and prop up the Pinochet regime.

But we know less about Australia’s involvement. We know Australian spies were stationed in Santiago at the time. We don’t know what exactly they were doing there. Soon that could change. Tomorrow the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) will hear a case which could reveal the extent of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service’s (ASIS) involvement in the coup, following a four-year campaign by UNSW Canberra Professor Clinton Fernandes.

But the government and intelligence agencies are battling to keep that information secret.

How the West broke Chile

To understand what Australian spies were doing in Chile, we need to understand the country’s tragic history. In 1970 Allende became the first democratically elected Marxist head of state in the Americas. US president Richard Nixon was furious, and wanted Allende gone. According to the sinister logic of cold war realpolitik, Allende was a threat who would bring Marxism to the Western hemisphere.

Desperate to stop Allende taking office after a narrow election win, the US tried to stage a coup. First, it had Rene Schneider, the apolitical head of the country’s armed forces, murdered in a kidnapping attempt gone wrong. The killers were paid off by the CIA in hush money.

The assassination of Schneider backfired. Chileans, fed up with foreign meddling, rallied around Allende, and his victory was soon ratified by the country’s congress. Two days later, Nixon gathered his national security council to discuss ways to “bring about his downfall”. It did that by creating a “coup climate”, helping engineer so much economic, social and political upheaval that the military would feel bound to intervene and remove Allende. It took just three years.

We know all this because when it comes to disclosure about what their spies were up to the Americans are far better than we are. Most information on Chile was released at a Senate committee in 1975 and in 1999, when the Clinton administration began declassifying pages of documents about Chile after Pinochet’s arrest in London for human rights violations.

Australia’s involvement remains far more opaque, and everything we do know is pieced together from royal commission reports and public statements made decades ago.

In 1971, prime minister Billy McMahon stationed ASIS officers in Santiago at the Americans’ request. Importantly, until newspapers broke a series of sensational stories in 1972 most Australians, even those in high levels of government, didn’t even know about the existence of ASIS, set up by Robert Menzies two decades earlier.

Months into his term, Gough Whitlam discovered the presence of ASIS officers and ordered their removal in early 1973. He would later confirm before Parliament in 1977 that ASIS had been in Chile.

But we know at least one ASIS agent remained in Chile until October 1973, a month after the coup. We also know ASIO officers (the agency which normally handles domestic security matters) remained in Chile, posing as migration agents and assisting the CIA until after the coup.

The secret hearing

The historical account of Australian involvement we are left with is thoroughly unsatisfactory and incomplete. So in 2017 Fernandes applied to the National Archives to get documents about ASIS’s role in Chile released.

“There’s no way for us to say we weren’t involved,” Fernandes said. “It may be that it’s not just some minor, tangential involvement. It may well be precisely because of our remoteness, we were useful to the CIA.”

Two years after applying, the agency refused him, citing an exemption in the Archives Act which prohibits release of material that could damage the “security, defence or international relations” of the Commonwealth. Coincidentally, the archives are headed by David Fricker, a former deputy director-general of ASIO.

Fernandes challenged that decision in the AAT. Tomorrow morning he will present his case, accompanied by barrister Ian Latham, who has assisted him on similar disclosure matters. After that, the room will be cleared, and for the next two and a half days the case against disclosure will be presented in secret.

That’s because ahead of the hearing, Attorney-General Michaelia Cash issued a public interest certificate, which means submissions made by intelligence agencies and evidence adduced to support the suppression of documents will be made entirely in secret. If the tribunal decides not to release the information, we will never know why.

In a letter seen by Crikey, Cash writes that she’s satisfied disclosure of information would be contrary to the public interest because it would “prejudice the security, defence or international relations of Australia”.

The public interest certificate is incredibly broad. It means Fernandes will have no opportunity to see or test the evidence against his application. It also means the evidence upon which Cash based her decision to issue the certificate will also stay secret.

From what we know, the secret case against disclosure so far seems to hinge on confidential affidavits from three people: one from ASIO, another from ASIS, and a high-level official with an intelligence background at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The ASIO and ASIS officers are providing evidence under assumed identities, standard practice in cases involving undercover work or terrorism offences, but unusual for a declassification case. All three will provide secret evidence.

“Basically, it’s the intelligence community using these tricks to conceal evidence of past crimes,” Fernandes said.

Cash’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

Independent Senator Rex Patrick, a long campaigner for better transparency, said it was “beyond comprehension” that the government and security agencies would “seek to suppress our history in this way” given other countries like the US and UK have opened up similar files.

“I wonder if the irony was lost on Attorney-General Michaelia Cash as she signed a secrecy certificate covering events that took place before she was even born,” he said.

In the almost 50 years since the coup, the world, and the country, have moved on. The cold war ended. Pinochet died 15 years ago, never convicted of a series of crimes. Chile is rewriting its junta-era constitution.

But the paranoid secrecy of Australia’s intelligence community remains.

Could the suppression of the Chile events be related to the fact that it was a Liberal-Country Party government involved in joining the US-led dirty work. Think of the energy and human pain associated with their keeping Downer and Costello’s names out of us undertaking illegal bugging of the independent Timor-Leste government. Anything to avoid the whiff of a continuous history of LNP-led illegality, murder and scandal.

As the American files are open surely they must contain material as to Australian involvement.?

Chile coup was the original 9/11 (11th Sept 1973). Most Americans look blankly at you when your response to them (when 9/11 comes up in conversation) is ‘which one’? Chile or New York? Lest they forget.

I’ve never believed Allende shot himself. Poor Chile. In fact, poor anybody, once the CIA latch onto them. Thankfully there’s no Pinochet in our army. Quite a few CIA liaison officers but. And we’re up to the tits in propaganda. Nah! Couldn’t happen here.

Actually, it looks as if it’d be quite hard to shoot yourself with an AK 47.

I don’t think there are many people who believe Allende shot himself. With an AK47???

As usual K N-R reads the first para. of Wiki and considers that research.

Maybe it was special AK47, as it was given to him by the Great US Bogeyman, F. Castro hissownself.

The Whitlam government suffered the same fate as the Allende government, just in a different way. The Americanisation of Australia is happening before our eyes.

Anyone who was paying attention in 1973 became ‘very afraid’ when Marshall Greene was appointed as US Ambassador to Australia. His previous gig in the region was as US Ambassador to Indonesia (1965)..that went ‘well’!

The dismissal of the Whitlam Government in 1975 with help from Governor General Kerr, who was not only the Queen’s representative, but part of the Anglo American intelligence establishment.

He was leading light in the Australian Association for Cultural Freedom, described by Jonathan Kwitny of the Wall Street Journal in his book, The Crimes of Patriots, as “an elite, invitation-only group … exposed in Congress as being founded, funded and generally run by the CIA”. The CIA “paid for Kerr’s travel, built his prestige … Kerr continued to go to the CIA for money”.(1)

Whitlam had enabled a royal commission into intelligence agencies, headed by Justice Robert Hope in 1974. In the US, the Watergate scandal and hearings had shown CIA involvement in domestic politics, and a further investigatory committee was established (the Church Committee). For the security agencies, it was clearly war with elected governments.

This as well as the actions taken by the CIA itself in regard to Pine Gap which allowed global surveillance and also domestic Australian surveillance, thus allowing it to monitor anti-Viet Nam -US-alliance political activity, all revealed at the trial of “falcon/snowman” spy Christopher Boyce in 1977.(2)

The CIA extended its domestic subversive activities, including the establishment of the Sydney-based Nugan Hand Bank, as a focus for channelling money, funded by drug and arms sales, used for subversion around the world.(3)

The Hope Royal Commission in one of its outcomes made ASIO accountable to the government and thus the Australian people and upset the ASIO applecart to a certain extent1that assisted in the removal of a democratically elected government by initiating the dismissal of the Whitlam Government in 1975 with help from Governor General Kerr, who was not only the Queen’s representative, but part of the Anglo American intelligence establishment.

(1)The Crimes of Patriots: A True Tale of Dope, Dirty Money, and the CIA/Jonathan Kwitny

W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY; 1987 ISBN:9780393336658

LC: HG3448.N846 K95 1987 LC:JQ4029.S4 T66 2019

(2)Boyce claims that he began getting misrouted cables from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) discussing the agency’s desire to depose the government of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in Australia. Boyce claimed the CIA wanted Whitlam removed from office because he wanted to close U.S. military bases in Australia, including the vital Pine Gap secure communications facility, and withdraw Australian troops from Vietnam. For these reasons some claim that U.S. government pressure was a major factor in the dismissal of Whitlam as Prime Minister by the Governor General, Sir John Kerr, who according to Boyce, was referred to as “our man Kerr” by CIA officers. Through the cable traffic Boyce saw that the CIA was involving itself in such a manner, not just with Australia but with other democratic, industrialized allies. Boyce considered going to the press, but believed the media’s earlier disclosure of CIA involvement in the 1973 Chilean coup d’état had not changed anything for the better….grâce à wikipedia

(3)The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade/ Alfred W. McCoy, with Cathleen B. Read and Leonard P. Adams II.

New York, NY:Harper & Row:1972

ISBN:0060129018 LC: HV5822.H4 M33 1972

Cocaine politics : drugs, armies, and the CIA in Central America

Peter Dale Scott ; Jonathan Marshall

Berkeley : University of California Press, c1991

ISBN:0520073126 LC: HV 5840 .C45 S36 1991

Whiteout : the CIA, drugs and the press: Alexander Cockburn ; Jeffrey St. Clair

Paperback ed., London ; New York : Verso, 1999

ISBN:1859841392 LC:HV 5825 .C59 1998

It has also been recently revealed that the then chief of CIA Counterintelligence from 1954 to 1975, James Jesus Angleton, in the year before the Dismissal had already wanted to have the Whitlam Government removed from power.

Brian Toohey relates this in his new publication, SECRET*… he obtained such information from John Walker the CIA chief of station in Australia during the Whitlam years… which is also confirmed… as Angleton said so in an interview with the ABC’s Correspondant’s Report in 1977. In the same interview, Angleton discussed how CIA funding in Australian politics and unions was handled.

SECRET The Making of Australia’s Security State/Brian Toohey

Melbourne University Press. 2019

ISBN 9780522872804 LC:JQ4029.S4 T66 2019

The penny now drops as to why the current head of the Australian National Archives was so recalcitrant in releasing the Queen/Kerr correspondence, because he, David Fricker was a former DDG of ASIO!

Graham Freudenberg’s “A Certain Grandeur” bio. of Whitlam, published 1977 confirmed that Kerr was known – even then – to be a CIA asset via the Australian Association for Cultural Freedom.

Also The Politics of Heroin in South East Asia by Alfred W McCoy looks at the CIA’s role in the heroin trade….