The charity commissioner has more power than the Australian Securities and Investments Commission commissioner and the commissioner of taxation and, if proposed reforms are passed, will soon be able to penalise charities if their members are suspected of committing minor offences (such as not moving on when directed by police, or trespassing) even if they’re never charged.

It’s been deemed an unconstitutional overreach by many in the sector, as well as unnecessary: in Senate estimates it was revealed only two “activist” charities lost their charity status for breaking the law, yet 59,000 charities will be affected by the reforms.

It’s a strange U-turn from a government that before coming into power advocated against the sector’s regulator, the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC), and its wide-reaching powers.

Organisations have also warned they’re becoming so wrapped up in red tape they’re spending less and less time and resources on providing key services.

What’s recommended?

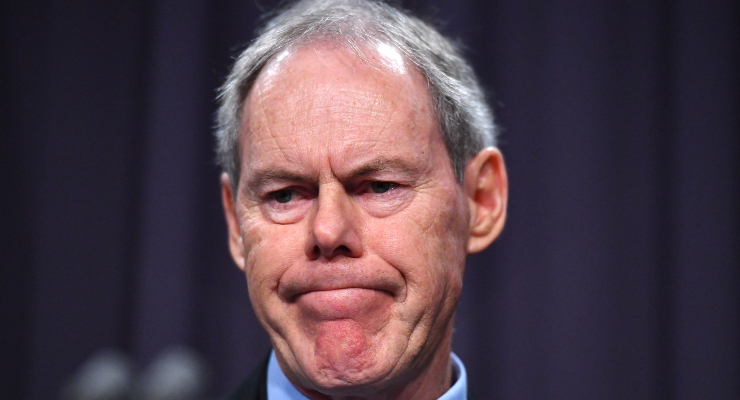

The reforms bolster existing government standards. Currently ACNC commissioner Gary Johns can deregister a charity if its members are suspected of committing a serious offence and show a pattern or likely purpose in engaging in unlawful activities.

The reforms will extend this to summary, or minor, offences. Charity law adviser Murray Baird tells Crikey the legislation could have wide-ranging consequences.

“When it comes down to summary offences … that takes you into the area of things that can happen at a protest rally or just in normal day-to-day affairs of a charity,” he said.

“That’s why this is so insidious. It’s a disproportionate burden, but it’s also discriminatory.”

More than 200 charities are drafting an open letter against the reforms, and law firms have deemed the change “unconstitutional”. In a submission to the draft legislation, law firm Arnold Bloch Leibler slammed the reforms as being a “clear fetter on freedom of political communication and on dissent by civil society”.

The current standards for serious offences have been criticised for years; a 2018 review found they’re inappropriate because avenues to deal with lawbreakers — regardless of their association with a charity — already exist.

In estimates, Johns rebuffed the idea the reforms would have a major impact on the ground.

“Our approach is as it’s always been, nothing has really changed,” he said. “We’re not a police force or a court. We would wait for others to reassure us that an offence has taken place, then we would think about approaching the charity and having discussions with it.”

So why implement the reforms at all? Community Council of Australia CEO David Crosbie tells Crikey there were concerns the reforms could be used to target specific charities, though he says it seemed like a roundabout method.

“There must be [fewer] than 20 charities [the government has] serious concerns about, so to impose an incredibly onerous requirement for charities to monitor all their supporters and staff and make sure they’re not supporting any action that may involve a summary event [is strange].”

The reforms could, however, be a kind of “Trojan horse” to crack down on charities where states had gone soft by penalising protestors and people who trespass, Crosbie said.

Half a decade of halting charities

The Coalition’s tightening on charities is nothing new: MPs initially opposed the creation of the ACNC in early 2013, arguing it shouldn’t have policing powers and against the commission’s “extraordinary overreach”. Unlike the commissioner of taxation, the ACNC commissioner can keep the reason for revoking a charity’s status secret and, unlike the ASIC’s head, can not only remove a charity’s leader but can replace them with a person of their choosing.

The Abbott government also introduced a bill to repeal the ACNC and have charities regulated by the Australian Tax Office, despite overwhelming support for the ACNC within the sector.

But after appointing Johns in 2017, the government changed its tune and soon began fighting for the regulator to have more powers. It introduced laws to limit the use of donations from overseas for advocacy, started writing warning letters to charities using their platform for advocacy, proposed environmental groups spend at least a quarter of their money on non-activist work, such as revegetation — an initiative supported by the mining lobby — and has continuously pushed for some environmental and animal rights charities to lose their charity taxation status.

As Labor’s Andrew Leigh put it: “[The Coalition] believes social service charities should serve soup at a soup kitchen but shouldn’t talk about poverty.” The Coalition argues these reforms strengthen the public’s faith in the charity sector.

Johns’ appointment has been widely criticised: he has previously called Indigenous mothers “cash cows”, criticised Beyond Blue for saying LGBTI Australians faced greater mental health risks because of “violence, prejudice and discrimination”, has argued for mandatory contraception for welfare recipients and accused charities of being “campaigns to give aid to Third World kleptomaniacs“.

Staff morale dropped following his appointment.

Last August, as charities struggled during the pandemic, Johns said groups should look to themselves for solutions and that waiting for the government’s help would be a mistake. “Don’t wait for a government to come up with an answer,” he said.

He’s also been criticised for his spending, racking up a huge bill taking near-weekly return flights from his home city of Brisbane to Melbourne, where the ACNC office is, costing taxpayers more than $300,000 in accommodation, flights and travel allowance since he took the role.

Conversely, Johns is an advocate for reducing red tape for the charity sector. A recent report found one in five charities believe current regulations are a huge barrier to fundraising, with the proposed legislation likely to complicate things.

The sector is vital

There are more than 59,000 charities in Australia, employing 1.38 million staff — or 11% of the workforce and contributing 8.5% to the GDP. The government increasingly relies on charities to deliver key outsourced government programs and services such as community housing and food programs.

“Every time we get criticised as charities, we get criticised for spending too much time on administration and not enough delivering frontline services,” Crosbie said.

We’re already more regulated than business, we have to provide an annual report to the charities regulator, we have to comply with a whole range of funding requirements for any money we get from governments.

Philanthropy Australia CEO Jack Heath tells Crikey charities are more important now than ever, and the reforms would have a huge impact on donations.

“Following bushfires, droughts, floods and COVID-19, the importance of the charitable sector is greater than it’s ever been before,” he said.

“These regulations are going to make it harder for charities to be able to fundraise, but also just to exercise those basic advocacy platforms and programs that have been so fundamental to what we accept as providing basic human rights.”

The ACNC referred Crikey to comments made in Senate estimates and said Johns was appointed to the role based on a merit-based selection process. Assistant Treasurer Michael Sukkar didn’t respond to Crikey’s request for a comment.

What do you think? Is the government waging a war on the not-for-profit sector? Write to letters@crikey.com.au (including your full name if you’d like to considered for publication).

Call it like it is. Johns and the ACNC are pursuing their ‘reforms’ precisely to punish GetUp and the more active environmental groups. The Liberal Party hate them, the Liberal Party backers hate them, News Corp hate them, and its time for a slow moving Kristallnacht that will jail or remove the subversives for good. After that, the commies at the ABC, the unions, and their industry superannuation funds. Seriously, the Liberal Right could be in a position to reign for decades, and we’ll be left muttering Martin Niemoller’s lament.

It’s the very reason that GetUp is not a charity, so they could go about their business without being shackled by government policy.

“GetUp is not a charity” – despite constant claims of EricA, Blot, et al.

Would that be the same the Gary Johns who, after 9 years as a Labor seat warmer was thrown out and became as senior fellow at the IPA as head of its Non-Government Organisations unit?

He is a columnist for NewsCorpse and flak for the tobacco industry as director of the “Australian Institute for Progress” (sic!), the author of numerous papers and books: Waking up to Dreamtime. Media Masters (2001), Aboriginal Self-determination. Connor Court (2011), No Contraception, No Dole. Connor Court (2016),The Charity Ball. Connor Court (2014), Right Social Justice. Connor Court (2012), Really Dangerous Ideas. Connor Court (2013), and Recognise What? Connor Court (2014).

He also worked for the International Tax and Investment Center (ITIC), a policy institute that received funding from the tobacco-industry. As a consultant for the ITIC Johns was scathing of the anti-smoking Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance, calling it “an instrument of the World Health Organisation”

That’s him 🙂 Classic GOP/Koch type modus operandi or astroturfing in leveraging former politicians from the centre and left…. IPA is in the Koch’s global AtlasNetwork, whose ‘bill mill’ ALEC also promotes constraints on NGOs and alternative voices (universities, media etc….)…… as seen in ‘illiberal democracies’ like Turkey, Russia, Poland and Hungary.

Isn’t it bizarre that calling an organisation ‘an instrument of the WHO’ would be seen as scathing?

Is there a more pitiable character than someone who spends much of his productive life making a career out of left politics who in his latter years becomes a caricature of right politics, playing harder than those who have been lifelong rightists. There are many examples that come to mind, but much less going the other way. Could be just my memory though.

As for me, I’m off to buy my IPA t-shirt and then get myself arrested for some summary offence.

The only rightists I can recall who saw the light and left the Dark Side are Robert Manne and, far too late in life, Malcolm Frazer, aka the Razor enabled by a nasty little twerp of a Treasurer, whose name I’ve expunged from memory… wonder what happened to him? Hopefully nothing good.

Can anyone else suggest others?

Naomi Wolf seems to be showing us the model, db. Too much exposure causes them to overextend on the rhetoric. Rather than look like a fool and be condemned as one, they seek refuge in the loony right. They still look like a fool, but there’s no longer any need to apologise.

The gov’t needs to quell dissent. They see certain charities as dissenters, particularly those that expose the shallowness of governments.

The serious iniquity here is not the generalisation of fascist restraints on active citizenship to the whole NFP sector, it is the philosophy of the restraint itself. It is OK for corporations to engage in corrupt influence with impunity and get rewarded with free rents, but real citizens must face criminality for dissent. This follows on from Rundle’s piece yesterday. This is the fascism of cowardly and corrupt managerialism in substitution for the courage required for social and political leadership, and vision.

The meaning of ‘quiet Australians’ flows from this.

Quiet Australians are, by definition, manipulated Australians.

Else they’d be loud and angry as hell and not prepared to cop it anymore.