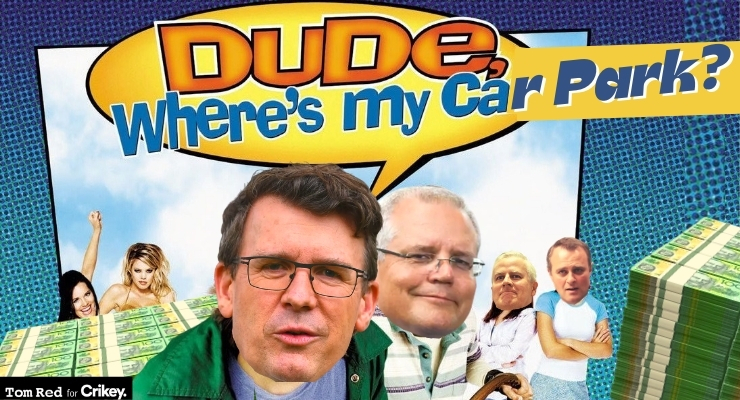

From the moment it was created, the “$500 million National Commuter Car Park Fund” was a rort. And public servants in the Department of Infrastructure treated it that way.

As Crikey reported earlier this week, the fund was part of an Urban Congestion Fund (UCF) established by the Turnbull government in 2018, initially costing $1 billion, with the idea that it would be based on a competitive selection process on publicly available guidelines to choose the most effective projects.

This reflected a key change by Malcolm Turnbull as prime minister: the Coalition abandoned its long-term reluctance about Commonwealth investment in cities. Traditionally, the Coalition had only spent infrastructure funding in regional areas, where it could be pork-barrelled to the advantage of Nationals ministers, who controlled the Transport/Infrastructure portfolio. Turnbull had also heeded the Reserve Bank’s repeated calls for a “pipeline” of infrastructure projects over a long-term planning period.

But Labor had a sexier plan: Shorten and Anthony Albanese would spend $300 million on park-and-ride facilities at metropolitan train stations, if elected. Albanese toured train stations across the country announcing how many extra parking spots would be built.

Once Scott Morrison became prime minister and the task of saving the electoral furniture — or even of snatching a remarkable victory — became the sole focus of the government, the Coalition decided it liked what it saw from Labor.

According to the auditor-general’s report on the car park rorts, the first step was to dump the idea of the UCF being based on a competitive process. Instead, the government would pick the projects. Some “principles” around the UCF would be released, but states and local governments were not to be asked to submit projects.

Then in November 2018, as part of the preparation for the 2019 pre-election budget, the then-cities minister Alan Tudge’s office demanded the Infrastructure Department, under now-Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy, prepare a “park and ride” program costing $250 million. Some commuter car parks had already been identified as potential UCF projects under the initial $1 billion fund.

But Tudge wanted a specific sub-program. However, because the Commonwealth had never funded anything as small as a train station car park before, no one had any idea what they would cost. Infrastructure bureaucrats scoured state government announcements for costing details — and even Labor’s announcements, released as part of what turned out to be Bill Shorten and Chris Bowen’s foolish strategy of complete transparency about their policies.

The government wasn’t just stealing Labor’s policies, it was using Labor’s costings as the basis for its own policies.

The department told Tudge maybe he could get 40 projects if they were co-funded with the states. And that was the limit of the policy work for what would become, by the time of the 2019 budget in early April, a $500 million car park fund, in order to outdo Labor. In the meantime, Tudge and Morrison had sat down and developed a list of car park projects they would fund, based on what electorates they wanted to target in the campaign.

It seems clear from the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) report that the Infrastructure Department knew right from the outset that this was a giant rort.

Not only was its recordkeeping around the project poor, with no evaluation plan (or even any KPIs) developed to see if several hundred million dollars of taxpayer money had been well spent, but the ANAO could find no documents showing the Department of Infrastructure ever developed a plan for identifying projects even at the earliest stages when Tudge asked for car park fund ideas.

Almost as if they knew that their services wouldn’t be required when it came to identifying where money should be spent to “bust congestion”.

The fly in the ointment was that the states were supposed to be involved. After all, they were going to co-fund them. And the very vague guidelines for the UCF said projects would be identified “through ongoing engagement with relevant stakeholders, including state, territory and local governments, members of parliament and other political representatives, advocacy groups and the private sector”.

The ANAO asked the department if it had ever consulted with state governments, or any other stakeholders, about the UCF. In response, the department produced a single brief from the end of 2018 showing it had told portfolio minister Michael McCormack that it “will also hold officials’ level discussions with jurisdictions on state priorities”.

So, the ANAO went and asked the states if this ever happened. The answers came back: no, never. One state agency said it had tried to find out whether it could apply to the fund by looking on Infrastructure’s website, but there was nothing there. The only contact with a state government was when Tudge’s office called the office of a NSW state Liberal minister to ask about a project.

Is this a new standard in the Australian Public Service? Are there now two sets of programs being administered with the Commonwealth? One where normal processes and good administration are at least attempted; another where bureaucrats know that the fix is in, that the whole thing is a rort, and simply let the minister’s office get on with rorting it?

If so, it’s another stage in the normalisation of corruption and maladministration in what was once one of the world’s best public services.

A program that seems absolutely typical of Morrison. That is, it’s almost entirely geared towards announcements, with the aim of presenting Morrison in a positive light; but unfortunately, there’s very little focus on practical planning, consultation, implementation and accountability. Essentially, he’s misusing public funds, in order to claim that he’s a better manager of public funds.

“Somebody else’s money’s no object” when it comes to that presentation/promo of Morrison’s industrial strength ego…. Just like when he was in “tourism” that couple of times – before being flushed?

Or before he stuffed things and then managed to fail upwards. Which is a recurrent pattern in his career. Which makes me think that he may be soon moving on. I mean, there’s an increasing number of people, who are demanding that he does more than just make announcements, so he’s probably eyeing up something a bit more cushy. Like an ambassadorship or corporate lobbyist.

How about first man/rorter on the moon, or mars, or anywhere far far away?

Why stop there? Fire the entire party into the sun if you ask me.

Yes please…. on a one way trip. Gosh wouldn’t that do the world & us a favour!!!

“very little focus on practical planning, consultation, implementation and accountability”

Isn’t that why Fran Bailey sacked him as CEO of Tourism Australia?

Wasn’t that also the reason he got the arse from its NZ equivalent ‘DF’?

Australia has degenerated into a country where tax-payers fund the Coalition’s rorting.

I would have bet my left one that ‘Todger’ Tudge would be in there up to his neck in this

If Tudgy, then Dodgy.

“Tudgy feely.”

Todger Tugger – the kid with the sweaty mien to whom no-one ever wanted to be too close.

The more we learn, the more clear it becomes that the Coalition’s 2019 victory was no “miracle”, just garden variety corruption.

Getting over the line with the rortung of the electoral system by Clive Palmer who’s the candidates were on concerned about nominating eligibility or filling out there nomination forms. Enabling preferences to be handed over to the Queensland LNP what a miracle that was, debatable whether Morrison’s cult fairy god or his cult Satan had the most to do with it

Sorry about that speech-to-text never reliable when using the mobile phone

There is not a lot more can be said about status of Australian governance. Parliamentary standards, Departmental Public Service complicity, both active and passive. Corruption once set free gains momentum, steam rolls transparency, accountability, and the final evidence . . . acceptability!

Corruption feeds on itself …. getting bigger and hungrier.

And now affecting the bureaucracy – with the dept failing to provide frank and fearless advice on adherence to financial guidelines. Infrastructure Secretary Simon Atkinson, after his ludicrously silly attempt to justify the rort as an election commitment, is not fit to continue in the job. We want honest public servants, not spineless toadies.