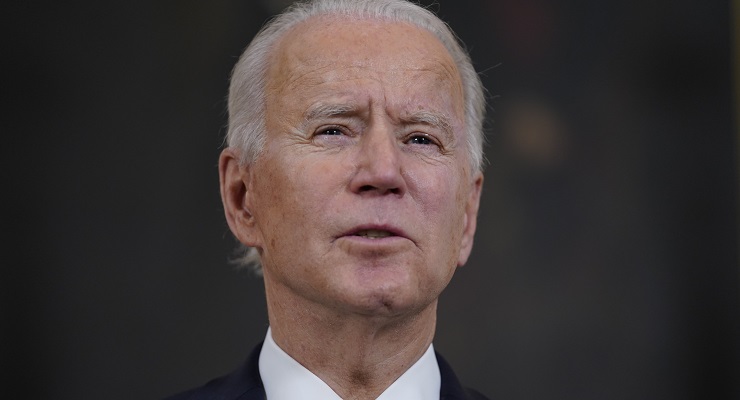

The emerging conventional wisdom in Washington is that US President Joe Biden was disastrously wrong in his assessment of Afghanistan — especially since he declared a little more than a month ago that the Afghan national forces would fight, and possibly dominate, the Taliban.

Further painting himself into a rhetorical corner, Biden added: “Never has Afghanistan been a united country, not in all of its history.”

Now that the Taliban seem to have more control of the country than they did even in the late 1990s, that latter Biden appraisal is looking very wrong as well. Afghanistan will now be united all right, but in blood. Very likely a reign of terror by the Pashtun-dominated Taliban will ensue as they subjugate Afghanistan’s large and hostile non-Pashtun ethnic population, such as the Tajiks and Hazaras (the second and third largest ethnic groups, respectively).

Yet in strategic terms Biden may have been essentially right in saying there was no reason for the United States to stay any longer; the Afghan state and its security forces were plainly an empty husk, utterly unable to operate on their own, and any further US involvement would not have altered the military odds, only staving off the inevitable. That has been Biden’s line all along.

As Biden said at the White House on Monday: “We gave them every chance to determine their own future. What we could not provide them was the will to fight for their future.”

Or as US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan told NBC News on Monday: “Despite the fact that we spent 20 years and tens of billions of dollars to give the best equipment, the best training, and the best capacity to the Afghan national security forces, we could not give them the will.”

Conventional wisdom may be overreacting as well when it comes to the political fallout for Biden. For an administration that had been coasting along on economic success and claiming some progress on climate and other foreign-policy issues, the Afghan debacle clearly marks the first major setback for Biden.

Hence, many pundits are predicting that “Biden’s Vietnam” bodes political catastrophe for him. But the very swiftness of the Taliban takeover could also work, ironically, to his political advantage: by the time the 2022 midterms and 2024 presidential election roll around, Afghanistan may no longer be making headlines, especially if the United States and its allies and the United Nations manage to restrain some Taliban behavior.

Charlie Black, a longtime Republican political strategist, said in an interview that while the Afghan debacle is a “national embarrassment and failure of leadership that dents his image forever … it probably won’t be a top-line issue in 2022 or 2024.” Black believes that the economy and the threat of inflation will loom larger.

Elaine Kamarck, a leading Democratic political strategist, tends to agree. “It’s a long time to the midterms,” she wrote in an email. “I doubt it will have much of an effect. After all [former US president Donald] Trump kept wanting to do this as well so it will be difficult to make it into a partisan issue.”

The emerging conventional wisdom also holds that the swift Taliban victory is a huge blow to US prestige abroad. And clearly US allies are worried about Washington’s broad retreat from trouble spots — especially in the Middle East.

But another way to read the situation is that Kabul’s stunningly swift collapse demonstrates just how crucial US military support is. Trump had reduced the US troop contingent to 2500 — though the actual number was about 3500 — after he began peace talks with the Taliban in 2020. Yet that small contingent alone, along with US air support, was enough to hold off the Taliban from doing more than taking control of mostly rural areas. It was only after Biden announced the coming withdrawal by August 31 that the Afghan national forces and police began to crumble. That demonstrates that even a small US presence in a country can make a difference.

Finally, many pundits are saying that the whole idea of US- and UN-led nation-building, which had been on a respirator in recent years, has now been delivered the coup de grâce. But has it?

Afghanistan was always a uniquely difficult problem, whose very geography seems to dictate its destiny as a nearly unconquerable land. As the scholar Larry Goodson wrote in his book Afghanistan’s Endless War in 2001, “The Hindu Kush and its various spurs not only limited Afghanistan’s enemies from their offensive tactics but also provided almost unassailable bases from which rival guerrillas could operate”. Whether it was the British in the 19th century or the Russians in the 20th, no great power has been able to overcome Afghanistan’s soaring mountains and ridges and tribal and ethnic disunity.

This was long the mantra of top US counterinsurgency experts under former president Barack Obama: true nation-building was never going to work there, so they had to settle for “Afghan good enough”, which meant mainly some modicum of stability and taking out the terrorists. The case can be made that the Afghanistan tragedy should be seen as the exception, not the rule.

Nonetheless it will take Biden a long time to recover from his huge tactical errors in Afghanistan, some experts say. Even if a Taliban takeover was inevitable, his insistence on a complete withdrawal with few contingency plans put the United States in the worst possible light.

“It was a mistake to announce a major foreign-policy decision without extensive consultation with our NATO allies and the Afghan government,” said Bruce Riedel, an advisor to four US presidents on the Middle East and South Central Asia. “It was also a mistake to begin a precipitous and hasty withdrawal at the beginning of the Afghan fighting season instead of at the end, when winter alone would have helped delay the Taliban.”

Biden and his team no doubt realise this now — and perhaps they’ll learn from it. “I’m not convinced that the Taliban takeover was inevitable,” said one former Biden aide in an email. “But US disengagement, and doing so without leaving any meaningful force behind (i.e. without even a residual capability at Bagram Air Base) probably tipped the balance.”

Instead of what might have been an alliance between the Afghan national forces and anti-Taliban warlords, the Taliban advance snowballed, and the warlords who might have resisted in the past folded.

This piece was originally published in Foreign Policy.

Michael Hirsh is a senior correspondent and deputy news editor at Foreign Policy.

Love all the worthy pundits today earnestly criticising Biden for not anticipating the speed of the Taliban takeover. Where were they a few weeks or months ago?

All that money did a good job training those soldiers. They could have fought and fought well. However they chose not to fight for a totally corrupt government that routinely sold their military equipment and even their food and medical supplies on the black market, often to the Taliban. No one would risk their lives for such a crappy government. I wouldnt have. I hope I dont hear any jokes about the Afghan soldiers fighting abilities.

Tend to agree Michael. Reports yesterday suggested they hadn’t been paid for 3 months and that the President probably took the money and ran. What person in their right mind would have fought for a corrupt, puppet government.

Ageed. Not that they couldn’t, rather they chose; and wisely, given the realities. Can they now find peace given the uniqueness of their land and their peoples? What is . . . possible, is the coming generation. Technology, education now seeded. Awareness, of a wider world. Will many stay, or many go? Again, they will choose, wisely. Will the world facilitate. Or deny, those we left behind?

And you know, another irony is that left alone the Taliban regime of 2001 may well have moderated by now or fallen apart under the pressures of modernity. Instead we now have what looks like a back to the future Taliban re-set. I hope I am wrong about the latter or that at least it is short-lived.

Eventually someone was going to have to clean up this mess – and it was never going to be neat and tidy.

The rotten remains of twenty years of a festering catastrophic diabolical, disastrous, ill-conceived, myopically prosecuted mess – a legacy to the lack of certain responsible Western governance.

I think you mean someone is going to have to clean up the mess. Morrison had better start praying for a miracle.

Whoever left was going to cop the opprobrium. It was just a case of whether they continued for 4, or 8, more years to hand on to the next President. Someone should have told them that going in was a mistake. Oh, that’s right, millions did.

I think the most compelling complaint is that they could have waited till winter set in to at least give a bit of time for those left to consider their options, plus it would have given Scotty from Marketing time to create some forms for them to fill out at our non-existent Consulate, to be speedily processed by our, ummhh, oh yeah, Dutton’s mob.

Maybe the end of the influence of the ‘industrial military complex’ Eisenhower warned about is finally upon us.

Will we stop interfering in other people’s business now ?

Oil is no longer the motivator it once was and America’s version of democracy is a laughable excuse.