As Taliban fighters broke through Kabul’s last defences and took control of Afghanistan’s capital city, residents received a WhatsApp message.

“The Islamic Emirate assures you that no one should be in panic of feeling fear,” one message said, according to The Washington Post. “Taliban is taking over the city without fighting and no one will be at risk.”

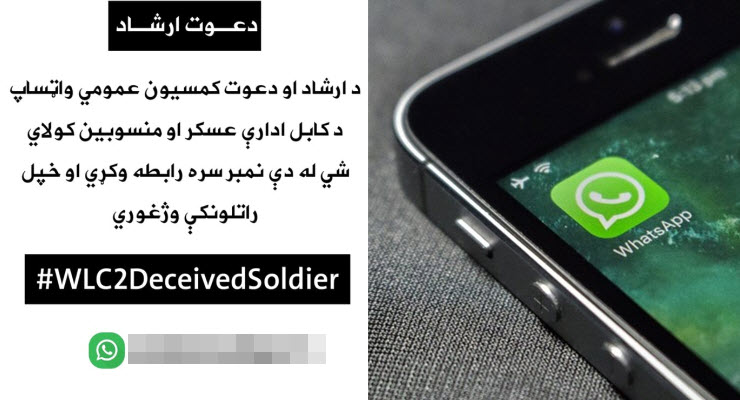

In the message, the Taliban listed WhatsApp numbers that residents could use to contact the “complaint commission”, similar to a 000 service, to report looting or other “irresponsible” behaviour.

The movement’s use of the Facebook-owned instant messaging service to establish the new regime’s infrastructure is no surprise.

The lightweight messaging app has become the de facto global communication infrastructure since it was invented in 2009. More than 2 billion people worldwide use WhatsApp. The platform is popular because it’s simple and flexible, free, available on both Android and Apple phones, uses little data, and is end-to-end encrypted which stymies government or corporate censorship.

Users can use WhatsApp to send text, voice or video messages or real-time audio or phone calls to individuals or groups.

In Afghanistan, WhatsApp has been an exceedingly popular platform with both the general population and Taliban for half a decade.

Despite their fundamentalism, the Taliban embraced social media over the past decade for the distribution of their communications. WhatsApp exists somewhere between personal communication and broader social media; it allows groups of up to 256 people, and the forwarding of messages. Taliban organisers used it to be in constant two-way contact with small, decentralised groups of Afghans, constantly repeating messages, forwarding central communications or answering questions.

It also served an important function for the operation of the Taliban organisation itself. It has been used to coordinate military action. Spokespeople for the group used WhatsApp to issue statements directly to journalists or to share Taliban-produced content with them.

WhatsApp has featured heavily as a medium for peace negotiations between Taliban and the United States. A 2019 New York Times article noted the distinct way the Taliban’s leadership used the service.

“They wouldn’t hold the phone to their ears to listen to WhatsApp messages, or put on headphones. Instead, they would disperse to far corners — around the bend from a little mosque, deep into the parking lot — with their phone in hand in front of them, like a military radio, the message playing out loud. Then, they would pace back and forth, the record button pressed as they sent a response message,” it said.

In 2017, the government threatened to ban the app because the country’s security agencies reportedly wanted to stop the Taliban. But they never followed through. A senior government official told the New York Times that such a ban could never be carried out because of its use for the administration.

“If we ban WhatsApp, how are we going to run the government?” they said.

As the Taliban made advances over the past few weeks, WhatsApp featured heavily. They set up numbers for surrendering police and officials to “call this number and save their future”. They listed WhatsApp numbers on official communications.

Now, some have called for tech platforms like WhatsApp to ban the Taliban from their services. Despite the violent and repressive nature of their movement, the Taliban is not on the United States’ list of designated foreign terrorist organizations used by some of the major tech platforms to determine which groups are banned.

Facebook, however, does list the Taliban as a banned group. So how are they still using WhatsApp? The end-to-end encryption means that Facebook can’t read the messages, meaning there’s no way of knowing who is Taliban and should be banned, according to Vice.

“As a private messaging service, we do not have access to the contents of people’s personal chats, however, if we become aware that a sanctioned individual or organization may have a presence on WhatsApp we take action,” the Facebook spokesperson said.

Senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab Emerson T. Brooking argued that removing the Taliban from WhatsApp lacks a strategic purpose.

“It would benefit no one to cripple one of Afghanistan’s main communications platforms as Taliban move to govern the country,” he tweeted.

Meanwhile, Afghans in captured cities used WhatsApp to communicate their despair. One translator who worked with German officials said that they were deleting their messages to avoid potential retaliation.

“Mazar is captured I’m deleting all ur messages,” they said. “Yes what will happen don’t know.”

Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp … Zuckerberg has much to be condemned for!

What more can be said . . .

Trump provided the means; and Taliban brilliantly organised, exploited opportunity. Not one western power publicly foreshadowed their opponents organisational capabilities. Or if they did . . . none wished to claim the privilege of informing their nation. ‘It will finish with a whimper’. And none, not one, will be accountable.

“Vale” to all that died. And, silence . . . for all those left behind, awaiting . . .

I wonder if the Taliban get served advertising on Whatsapp?

Even the Taliban is being used to garner clicks.

Gil Scot-Heron said that “The Revolution will Not be Televised” but will it be live?

Or still born for lack of interest as we amuse ourselves to death?

(Vale Neil Postman, his warning too soon forgotten.)

It’s hard to think of a technology that did not supersede its original function – it is just the sheer rapidity that now astounds.

Surely we all know the real reason WhatsApp will always be permitted, at least from the US end, is because the NSA pays FB to keep the back door open for them.