News Corp’s tabloids have been using their front pages as a modern-day pillory, a device for holding COVID rule-breakers up to public shame. And the mainstream media through its self-regulator, the Australian Press Council, says it’s totally fine – once the story is out there, what’s the harm in amplifying it?

Maybe so last century, when today’s newspaper could be brushed aside as tomorrow’s fish-and-chips wrapping. But in today’s virtual world the added power of social media can quickly mutate public shame into abuse.

The old media blame game has been transformed; it’s no longer “just the facts” reporting. It makes the media responsible for putting public shaming at the heart of public health compliance.

In shrugging off complaints over The Courier-Mail’s notorious “Enemies of the State” bannering of two young women of colour for COVID breaches last year, the council determined that their conviction was a matter of public record and therefore “their reasonable expectations of privacy had been diminished”.

Shaming was the point, with the council acknowledging “the headline is provocative given the language used and the prominence of the women’s images… the reporting reflects the seriousness of the women’s actions and risk to the community”.

Although the report triggered widespread racial vilification and death threats, the council seemed comforted by News Corp’s assurance that “it was difficult to anticipate social media responses to reports”.

Maybe it was difficult to anticipate — for anyone who hadn’t spent any time on Facebook or reading the newspaper’s own comments over the past decade.

There was, the council said confidently, no racism involved as the reporting was “not due to any personal characteristic of the women involved”.

President of Queensland’s African Communities Council Beny Bol was unconvinced: “It’s a very disappointing outcome because it sanctions racism, it sanctions racial vilification, and it sends a message that you can publish an article targeting a particular racial or religious group and that’s OK,” he told SBS.

Not to be outdone by its Brisbane sibling, Sydney’s News Corp tabloid The Daily Telegraph went a step further last week when it not only reported but apparently generated the COVID breach conviction of the driver who had been identified as the first local case in the current Sydney outbreak, having been infected while transporting visiting freight aircrew.

Stumbling across the driver standing apparently alone and mask-less at a Sydney bus stop, the paper snapped him and forwarded the picture to NSW Police, who charged him under public health orders. With that, the Tele had its full-page pic for Wednesday’s front page — restricted only by the now-standard Clive Palmer anti-lockdown ad strapped across the bottom — complete with the most literal of puns “BUSTED” and “LIMO DRIVER UNMASKED”.

The Australian, meanwhile, was overriding cultural sensitivities by reporting the name (and criminal record) of an Indigenous man who died of COVID in western NSW. In Melbourne, the best of the Herald Sun are still searching for the shame to own them all: the mysterious bonking security guard.

It’s the aesthetic of scolding that masquerades as accountability journalism: the marker of the worst of the journalism of these plague years.

Journalism has been grappling with punch-down shaming for decades. Way back in 1978 when the internet was just a gleam in the US Defence Department’s eye, The Sydney Morning Herald found itself at the beginning of a 38-year conflict with its own community when it published the names of protesters arrested in the city’s first gay and lesbian mardi gras.

It was not until 2016 that then editor-in-chief Darren Goodsir apologised, saying: “While it was routine to publish court attendance lists, these particular actions were a stark illustration of the harsh reality of the time — that the media was part of a broad array of political and social institutions that perpetuated the oppression of lesbians and gay men.”

The convention of reporting court lists, findings and convictions was a staple of 20th century “journalism of record” reporting. But now the convention is more selectively applied, it has become just another input tossed on to the production line at the social media outrage factory.

Things are not really going to change until till the world rids itself of the Covid Murdoch family virus.

Contrast that with the under reporting Bruce Lehrmann. Despite no ban on his name many outlets refused to name him ongoing. They published his name once when they could, then stopped voluntarily. Why is this?

Interesting question.

The only person who did publish that name, months before the legacy media, Shane Dowling in his Kangaroo Court, is facing 10 months incarceration for another act of lese majeste of the gross & grifting – pour effrayer les autres.

Perhaps that’s why?

Yeh Nah the action that Shane is likely to go to jail for has been playing out for a couple of years.

Yes, as I stated, “…another act of lese majeste of the gross..” but the effect in general, to terrify others into toeing the line, is the same.

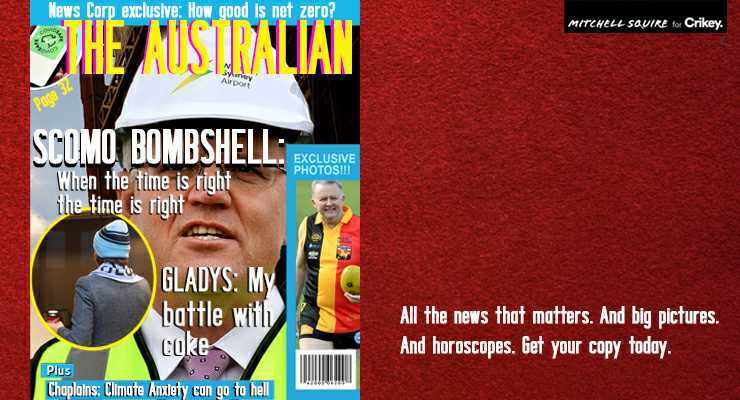

It’s not just bad journalism condoned by the self-interested “press council”, it is actually a political campaign to shift blame for any covid breach/ petty criminality onto the victims that News Ltd chooses from the hundreds possible each day, Australia-wide, in order to shift blame from the real cause of the covid meltdown in Australia – the covid-spreader-in-chief, Scotty.

And you’ll be stunned to know that the elderly, I’m going to guess white, couple who infected the northern beaches pre-Xmas Sydney last year were never outed, although I’m sure somebody knows who they are. No, it wasn’t Bryan Brown.

An excellent book describing this type of journalism, and much more, is “Bad Faith” by Australian author Carmen Callil. It describes the work of the gutter-press of right wing political factions in France in the 1930’s; where lists of people were named and shamed, and the locked in readers were invited to take personal action against them. Sounds rather like News Ltd tabloids of today, n’est ce pas?

Same book gave a less than flattering account of the activities of Erich’s uncle Otto.