“I wanted to do something really big with my life,’’ a Year 12 student from Melbourne told me yesterday. “But after more than 200 days of lockdown I just want to finish. I don’t care any more. Whatever. Nothing’s fair.’’

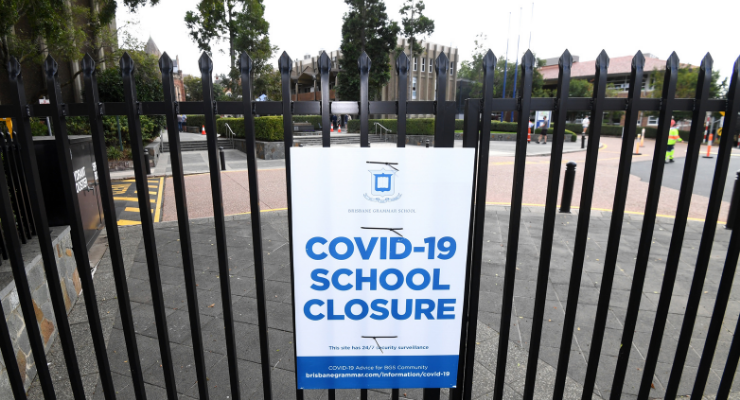

Let’s call her Amy. In Melbourne, there are Amys everywhere. In Sydney too. They’ve endured months and months of lockdown over their last two years of schooling. They’ve worked remotely, trying to stay motivated but without the social connections and hands-on learning that’s at the heart of school life.

“I just feel we’ve been forgotten,” she said. “Those doing Year 12 in rural Victoria or in other states haven’t been through what we have, and I know it will show in my results. Some of my friends have just given up. It’s not fair.’’

It’s not. And Amy’s year group, in Melbourne and Sydney, need more than the special consideration granted to last year’s graduates.

But it’s her focus on “fairness” that is at the heart of how she sees COVID-19. As jingoistic as it sounds we’ve always prided ourselves on being the land of the fair go. Fairness is the attribute we teach our young children — play fairly. And when they bring home the trophy of “best and fairest” it’s that latter complement that swells our pride.

Of course, life has always been unfair. Why does a child die before their parent? How can cancer snuff out the life of a young mother, whose devotion to organic food and exercise rivals the dedication she shows to her children? Why is someone else’s child chosen for a job? Why do some tiny communities, year after year, feel the force of cyclones? Why do bushfires steal the homes of those who spend their lives helping others? Why did Gladys Berejiklian choose such a dolt as a boyfriend? (Although, to be fair, many of us have travelled down that road…)

We’ve answered most of those questions around fairness with an understanding that there are always exceptions to the rule. Life’s fair — but it’s full of challenges and wrongdoing and inequities and discrimination — and even bad luck.

But just now, as Victoria scales back contact tracing and Queensland basks in NRL-hosting glory, our belief in “fairness” is taking an almighty beating. The end of disaster payments. The end of so many small businesses. Job losses. Rising COVID deaths. The disappearance of vital school years. Toddlers growing up not understanding the warmth of a smile, hidden by a mask. Cancelled weddings. Abandoned honeymoons. An 18th birthday celebrated in isolation.

COVID has challenged everything from our resilience to our drinking and exercise habits. But it’s also put a stake through a characteristic that sits at the heart of our national identity: a fundamental right to fairness.

It’s always been seen as part of our culture. Former PM Julia Gillard talked about “the fair go’’ at the heart of the NDIS. Robert Menzies and Malcolm Fraser used it in campaign speeches, and Kevin Rudd wanted a “fair shake of the sauce bottle”. We have written it into work laws with the Fair Work Commission, and a “fair crack of the whip” is supposed to provide us all with an equal chance.

It’s always been theoretical, with as many exceptions as examples. Now COVID is highlighting that every single day, in a way that is hurting thousands of Australians and our long history of state cooperation.

Yes, we’ve always fought over everything, from the size of train tracks to shares of federal funding, but it is how we police our borders that is seeding unfairness with greater speed than COVID-19 cases.

And unless we value our nation over the state where we reside, it will continue to grow. How can parts of Australia be open for Christmas and others closed? Why can’t Queenslanders, for example, return home? Should a politician — any politician — have the power to refuse its citizens the right to fly overseas, or to separate children from their families? Is there anything fair about capping the numbers of mourners at a funeral but allowing 40,000 NRL fans to hug and kiss and share a beer from a shoe?

Perhaps it was the NRL grand final, where many did not obey the restrictions around mask-wearing, that really highlights the “unfairness”. Or that’s how the 90-year-old who lives a stone’s throw from the NRL final saw it. He’s forbidden from visiting his wife in an aged care home because of restrictions around the latest outbreak. He just wants to know that she’s eating her dinner.

And in Melbourne, Amy just wants to know that sharing the kitchen table with her siblings during her final two years at school won’t prove to be the full stop on dreams she’s had as long as she can remember.

If you think Australia has ever been the land of the fair go, talk to one of the original inhabitants. It has never been anything but an advertising slogan used to deceive the unwary. Whenever I hear a politician talking about a fair go I know some new injustice is about to be visited upon the downtrodden.

“Why is the Limited News Party – that Madonna used to do PR for at Rupert’s Curry or Maul – so beholden to fossil fuel companies, at cost to our environment? Why doesn’t Madonna’s Limited News Party government do anything positive about climate change – for the world that our kids are going to inherit? Why would Madonna’s Limited News Party government think Robodebt was all right to continue lumping poor Australians with illegitimate debt – even after questions about it’s legitimacy were raised? Why is Madonna’s Limited News Party government so untruthful and corrupt? Why does Gladys think that pork barreling is all right because “everybody’s doing it”? Why didn’t/doesn’t Madonna write about that?”

Griselda, I concur completely. In fact, I made damn sure my kids had no illusions whatsoever of ‘fairness’ or that uniquely Aussie furphy ‘the fair go’. I knew that if they didn’t indulge in that sort of magical thinking then they would at least get through life with some mental balance and resilience if things didn’t happen to go their way. Not to mention the moments of pure tragedy that we all hope to avoid as best possible.

I saw this morning on my insight timer app a reference to the ‘greed, ignorance and hatred which are a root cause of suffering’ according to the Buddha. Time to cultivate community, sharing and the doughnut economy, time to be human again. The Australia Institute webinar this morning with Saul Griffith went a long way to restoring my optimism but the Pandora papers illustrate that good intention is no match for good regulation and that many people’s worst instincts will often hold sway.

Hence my life lesson to my daughters, don’t count on fairness or equality in society yet, unfortunately.

The current federal government has a mantra have a go get ago, which is code for you’re on your own Mate.

Australia as a ‘fair go’ nation has always been an urban myth, right up there with ‘can do’ nation. I will always think back to when my uncle, a highly qualified Dutch aircraft mechanic, who after the war, while on R&R from post war Indonesia, fell in love with my aunt, a local Brisbane girl. When they decided to get married they ran into a brick wall called the ‘white Australia policy’. You see, my uncle happened to be an Indonesian, didn’t matter he was Dutch. He was coloured. They were luckily able to get around it by marrying in proxy, after which he was allowed in. Even today, ask the average indigenous Australian if he/she feels they’ve had a fair go in this country in the last 200 years or so! Ask that poor Shri Lankan family, in lock up for so many years, if we’re a fair go nation.

“Fair white go”.

My father, when I was under school age, always replied to my “thats not fair”, tell that to a black fella, their face is never fair! think about it!!

Depending on your class, Klewso- depending on your class.

I think Mad King has had a fair go. She’s had a go now she’s got to go. Tugging at the heart strings for relevance is puerile.