Trending

Last week was the nail in the coffin for the idea that COVID-19 deaths can be prevented using ivermectin, an anti-parasitic drug lauded by the right, anti-vaxxers and conspiracy theorists.

The BBC reported that recent analysis shows none of the 26 major trials of the drug revealed promising results, and a third of those trials showed serious errors or evidence of fraud. The source of this analysis was a handful of guys spread across the globe — an epidemiologist, a medical researcher, a student, a data analyst and a chief science officer — who have been using Google Docs, Dropbox and Twitter to tackle and expose bad science in their spare time.

The idea that anyone can debunk bullshit is cool. On the other hand, it feels a bit grim that the burden of overturning evidence for the biggest problem in the world right now fell to five guys and not, like, the World Health Organization. I spoke to two Aussie members of the group, Kyle Sheldrick and Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, who explained to me how the world wide web changed everything about how science works now.

It used to be that you would submit something to a publication like Science and, after jumping through enough hoops, your research could be published. If you had doubts about a published study, you could respond by writing a letter to the publication. Months would pass before anything happens, if something happens.

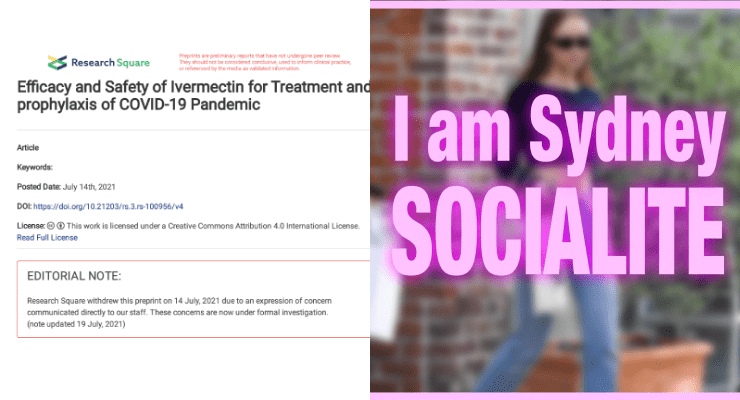

When the internet killed the gatekeeper, it opened the floodgates. Publishing your research became as easy as uploading it the internet — the eggheads call these “pre-print publications”— without the need for something as time consuming as a “peer review”.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, dodgy preprint studies have been going viral online as people search for answers. (Peer-reviewed work still happens and is important to legit journals, but it suffers from being too slow.)

People — like misinformation super-spreader Craig Kelly — can then shop around for a legit-looking PDF that “proves” what they already believed.

“There’s hundreds of papers coming out a day. If you were to publish fake ivermectin research, the chance of ever being found out is quite low,” Kyle told me.

The flipside is that a ragtag team of medical research mercenaries can shape scientific knowledge using a shared spreadsheet of studies to coordinate their checks on study methodology, and some nifty statistical analysis based on publicly available results and data requested from research authors.

Once they’ve done this work, they publish on Twitter and on their personal blogs. They engage with people on social media to explain what they did and review other people’s work. All this took was a bit of knowhow and curiosity on their parts.

Their reward? “I get no financial incentives, there are no career incentives. You get paid in hate mail and death threats even if you’re successful getting fraudulent research looked at,” Gideon said.

Whether this model of “a good guy with a spreadsheet is the solution to a bad guy with the spreadsheet” trumps our pre-internet scientific publishing model is moot — the internet genie is well and truly out of the bottle — and also a false choice. That’s because gate-kept science had its problems with fraud too! It’s just that the traditional methods of gatekeeping aren’t screening for fraud like Kyle and Gideon’s crew are.

This is a major problem with scientific rigour and the internet. How are we supposed to know what’s real? What chance does a mere mortal have to understand medical research when the world’s top experts haven’t been spotting fraud? Even with Kyle and Gideon’s analysis, I’m just taking their critique in good faith. They are transparent, but all the details are gobbledygook to me.

And in case you didn’t realise, this same problem is happening in just about every other domain of life too.

But their story gives me hope. The world could have ignored Gideon and Kyle’s analysis. Instead, the world’s most read publishers are reporting that the reputation of ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment is in tatters because of their work.

Sure, the internet is the problem here. But it’s offering us solutions too.

Hyperlinks

ASIC enters chat room to warn ‘pump and dump’ group

Can’t say I’ve ever laughed this much at an article from The Australian Financial Review. Unbelievable story. (AFR)

Save Australia: how social video has created a dystopian vision of Australia

I wrote about how a dystopian, warped version of Australia portrayed through viral videos and Fox News clips was being planted in minds of people around the world… and then a few days later a “Save Australia” protest took place outside of Australia’s consulate-general in New York! (Crikey)

‘Pay the price’: tech giants could face legal responsibility for trolls

The government is making noise about having another whack at big tech, this time regarding defamation on social media. It remains to be seen what, if anything, will eventuate, but there’s always something happening on Australia’s tech policy front. (Nine)

YouTube ban won’t shut down most Australian anti-vaccination channels

Despite its enormous popularity, YouTube doesn’t get a lot of scrutiny. Nine’s Dominic Powell did a good job framing news about YouTube’s latest policy announcement, looking at how moderating channels will actually work and not just how YouTube’s PR people would like you to believe. (Nine)

There’s something fishy about Craig Kelly and Clive Palmer’s YouTube views

Craig Kelly’s election ads for United Australia Party have millions of views. But I found out that all is not as it seems… (Crikey)

Content Corner

If you’ve looked at the Instagram story of a member of Gen Z, there’s a good chance you’ve come across an affirmation meme.

You’ll know them if you’ve seen them: they’re a short, tongue-in-cheek, positive and usually absurd message, often in pastel colours over a photo backdrop of specific city space.

Rolling Stone’s EJ Dickson explained their appeal well: “they’re a way to convey both the poster’s awareness of the silliness of using a piece of expertly algorithm-tailored content to telegraph identity, while simultaneously endorsing the underlying message therein. By adopting this type of ironic, detached voice to skewer social media tropes, zoomers are more able to achieve the unachievable on Instagram: to get one step closer to showing their true selves.”

They’ve taken off in Australia in the last few months (Zac Crellin rounded up the major cities pages for Pedestrian). But the ones I’ve really been enjoying are the hyperlocal ones.

I think there’s been another reason for this surge, beyond what Dickson notes: it’s a yearning for a familiar space that felt so far away during lockdown. There’s a positivity, somewhat ironic and somewhat earnest, that we will be sitting on the wooden benches with an ice cool jug of pale ale outside a crowded Courty in the not-too-distant future.

As we open up, I hope that our hyperlocal affirmations hang around.

Doctor John Campbell on Youtube didn’t have a high opinion of the BBC article (and he’s certianly not “antivax”) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zy7c_FHiEac

Definitely worth a watch Cam for a medical practitioners review of the paper and the reporting of it.