Scott Morrison’s net zero plan is called “The Australian Way”. The name is telling. The pamphlet handed to journalists yesterday containing a series of graphs and diagrams was another sign we’re going our own way on climate.

Beyond the spin and the bluster, the plan (a word mentioned 101 times in the press conference) gave us little new information about how Australia would reach net zero emissions, and left plenty of questions unanswered.

The plan is a nice principle, a sign that even some people in the Morrison government believe climate change is real — if not exactly a priority worth taking seriously. But it won’t be legislated, because legislation is what Labor does. You know the government thinks this is a winner because Deputy PM Barnaby Joyce keeps getting up in question time to accuse Labor of wanting to pass laws.

“Our plan works with Australians to achieve [net zero]. Our plan enables them, it doesn’t legislate them, it doesn’t mandate them, it doesn’t force them. It respects them,” the prime minister said.

Instead of passing laws and doing stuff, the plan will largely be achieved through technologies already flagged in the government’s roadmap (with the addition of cheap solar). But there’s vanishingly little new information on how those technologies will work to drive down emissions when, as Morrison flagged, it won’t affect coal or gas exports.

And so far, despite the Coalition’s fierce criticism of former Labor leader Bill Shorten’s failure to cost his climate policies at the last election, no modelling was provided.

“Today’s about the plan. We’ll release the modelling in due course,” Morrison said.

But a few “details” (or lack thereof) stand out. One is Morrison’s claim it would create 62,000 jobs in mining and heavy (read: polluting) industry. Morrison and Taylor didn’t clarify whether those jobs would come from carve-outs for those industries.

Another is the heavy reliance on carbon capture and storage to do heavy lifting, both as an offset mechanism and the bedrock of the government’s plan for clean hydrogen, despite little evidence that it has ever worked to reduce emissions.

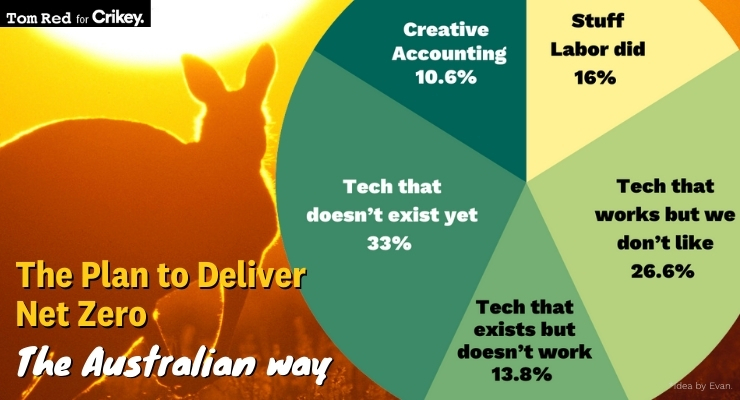

Finally, there’s the buried graph which suggests that 30% of Australia’s reduction in emissions would come from a combination of “global technology trends” and “further technology trends”. In other words, stuff that doesn’t exist yet. When pressed about this, Morrison pointed out that at JB Hi-Fi stores one can see technology on the shelves that wasn’t around five years ago.

If you needed any more proof this is a political document, rather than a serious plan to reduce emissions, it’s right here.

But the most glaring omission from Morrison’s victory presser was the refusal to name the price of buying the Nationals’ reluctant agreement to a net zero target, all but locked in when Joyce didn’t front the cameras yesterday. The only concession Morrison named was was confirmation that the Productivity Commission would do checks every five years to ensure the target wasn’t harming the regions.

But we know the Nationals’ price involved potential billions for the regions — in additional investment, a future fund, and tax breaks for farmers. Previously Nats had talked about total carve-outs for agriculture, for methane emissions. And they’ve effectively soft-committed to inland rail which as Crikey has repeatedly pointed out will open up the potential for a surge in coal exports.

Whether those other promises to mollify the junior Coalition partners will also allow an increase in emissions by stealth is unclear. Any investment into the regions strong-armed out of the government by the greatest pork-barrellers Australia has ever seen will come out between now and the election. Expect a slew of generous announcements to keep voters in coal country onside. Even in the Nationals’ act of climate extortion, the government has still found an opportunity to play politics.

One last little surprise was Morrison’s claim that more details on the expenses would come out in a budget next year. That can mean one of two things: that Morrison will use a splashy, generous budget as the launching pad for a May election, as he did in 2019. Or that he’s so confident the government will win, he’s already planning for another term. If voters don’t see through the marketing, he might be right.

I saw Angus TallTayles on the ABC this morning. Just how vacuous, full of spin and lies and devoid of anything remotely new this tripe masquerading as a plan is can be measured by how often he referred to Labor’s “carbon tax” – there’s nothing to sell in the LNP’s nonsensical re-hash of what they say they are already achieving (by lying about their actual performance on emissions), so they have to attack Labor. Now, I can’t recall if I have seen any interview with Talltayles over the last 2 years where, as far as I can tell, he hasn’t lied through his teeth, but this most recent interview felt to me like he plumbed a new nadir. This plan for nothing is only about Morrison not looking the puerile, mediocre and pratt’ish bozo he deserves to be seen as at COP26; wedging Labor e.g., the LNP “plan” is practical and realistic, but anything Labor comes up with will be economy-destroying and cost thousands of jobs) and the next election. I wonder if Morrison returns from COP26 cock-a-hoop because he thinks he has been with and conned the grown-ups into believing he has a genuine plan instead of pathetic slogans, if he would still think a pre-Christmas election is winnable.

I watched Angas on 7:30 last night (what a missed opportunity – unless you’re into waffles), then there was that piece on the self-interest of SA politicians (strangling their ICAC – on their ostensible grounds? Steve Murray could slip straight into Scotty FM’s cabinet – out of the light), then I watched “Big Deal” and the self-defenses the majors have built to protect their arses.

Reflecting on the supercilious, protected, entitled, private schooled, parsimonious, narcissist that is the core of that 7:30 Taylor – sermonising such errant BS – he knows the odds are in his favour that he can spin as much BS as he likes and he can’t be touched?

Correct. This is just a marketing exercise to get him thru the next few days in Glagow by providing a semiplausable, give me the benefit of the doubt sort of smoke screen. Trouble is they wont buy it. Hopefully we get hammered with crippling tarifs. Maybe also we get the emmissions from the coal we export added to our total and we have to offset it somehow. I would like to see how our fool government deals with that.

It may well be the thrashing Morrison gets from leaders in Glasgow (although Boris Johnson has already signalled he won’t do anything harsher to Morrison than pet him) that commits Morrison to do something – embarrassment can be a good motivator, even for someone as lazy as ScoMo. If Morrison gets wedged between the world leaders in Glasgow, and the toddleresque Nationals in the party room, it certainly could get awkward.

Those clowns will fawn over him as he shows them the cooked books, it worked on Pelosi.

I’d prefer “interesting”.

You actually need the ability to feel shame to be able to feel embarrassment. I see no problem ahead for the PM and Murdoch and Palmer will reap enough of the moron vote to get them back in parliament.

Alas you may be right. Unless the feckless Labor Party can get its act together.

Labor have developed a clever strategy to improve their odds of getting elected – make themselves identical to the LNP, so nobody can tell which is which. That way they have a 50% chance of winning

We can guarantee Australian media will curate COP26 news content so that Morrison does not look and sound like a complete idiot (muting the sound?) while ignoring any criticism of Australia. COP26 is over, he returns to Oz, then move on there is nothinf to see here….

That’s clearly the strategy. And the two bulwarks of the strategy are the Murdoch propaganda mill and Palmer’s strategically placed millions.

The “plan” (page 10) outlines “$20 billion of government investment in low emissions technology”. This in reality means fossil fuel funding to the regions – this will be the Nat’s payoff….

Carbon capture anyone.

The ‘plan’ indicates need for BS capture technology!

So 20 billion of our taxes are going to this technology?

“The Australian Way” means we spit the dummy at Kyoto and receive an ‘Australia Clause’ to actually increase our emissions target when other signatories agree to reduce theirs. We then boast that we “have achieved our Kyoto targets in a canter”. We repeal perfectly working Carbon legislation for “brutal retail politics”, We don’t accept the premise of any questioning. We squirm, we smirk and ultimately we renege on international conventions and billion dollar contracts with our friends. How did we get like this?

How did we get like this, Kishor? It seems that the wealthier we became as a society, say since the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, the less concerned we were for others. Not very satisfactory, but it’s really the best explanation I can come up with. We’re now one of the wealthiest countries that ever existed, yet we’re the meanest we’ve ever been. I don’t know how that works.

I’ve observed many many people now, especially over the last 20 years or so, who have little interest in what is going on outside of their family circle. They all want to “travel” (and do) but appear to learn nothing from their travels, only about what they ate. They don’t want to be disturbed by news about climate, inequality, social issues etc. etc. they just keep their head down and plan on spending their money on themselves. In other words – narcissists. They are prime picking for the LNP and vote for them even though in their earlier lives they might have voted progressive. I’m actually angry and disgusted that we have elected such an appalling government led by such an arrogant, stupid, God bothering imbecile of a prime minister and still disgusted that people fell for the crap and voted for him in the first place. Anyone who looked with clear eyes could see what sort of man he is.

Fear! Fear of losing it all again to “the other”

One thinks it shows the success of imported US KochNetwork political PR and media tactics used to ‘own’ the GOP and promote policies using the GOP as a delivery system while citizens become ‘freedom loving libertarians’ or wing nuts; look after no. 1 aka Buchanan’s ‘public choice theory’ promoted in the Anglosphere inc. Oz via the IPA etc.

And their latest trick is ID checks at elections to supposedly reduce (non-existent) voter fraud. Straight out of the fascist GOP playbook.

Definitely, but I made same comment y’day naming and linking to the actual US ‘bill mill’ drafting similar for state legislatures but was moderated then deleted…..

It was the Koch Network influenced A. L. E. C. who are scrutinised often in US media for support of big tobacco/packaging, especially fossil fuels (against environmental regulation) and now voter suppression ideas, but not locally in Oz, though they have an indirect presence.

Bill Moyers has a doco from almost …. a decade ago…. explaining their modus operandi in ‘United States of ***’ via PBS.

UK Tory Party has also mooted exactly the same ID laws (solution to a non problem); Anglosphere marching in goose steps…. will be interesting following non Oz media on the machinations round think tanks on the sidelines of COP26, cooking up ways to evade fossil fuel constraints….

Please add “stuff the states have already delivered or committed to: 68%” to the Net Zero Delivery wheel of nonsense.