Scott Morrison may have flown home from Glasgow, but other world leaders who haven’t royally embarrassed themselves remain at the COP26 summit as negotiations continue. Their challenge is no less than to arrest widespread, impending destruction of the natural world.

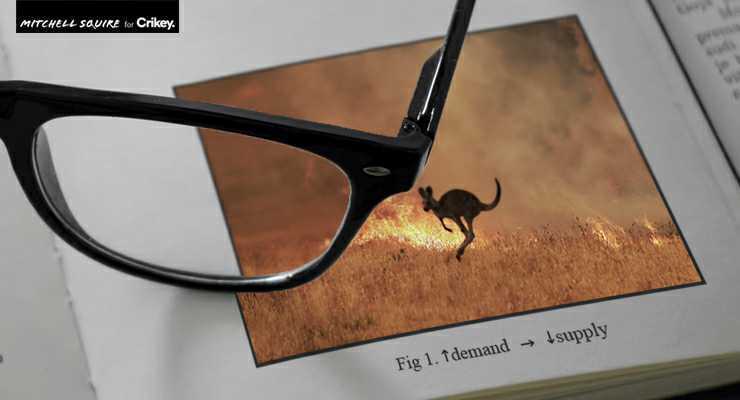

Among some thinkers and climate activists, an idea has risen to prominence: “degrowth”. Advocates posit that at global summits, nations should not simply commit to making their economic growth sustainable — they must be prepared to slash it.

Proponent Jason Hickel defines degrowth as “a planned reduction of energy and resource throughput designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world”. For Hickel, replacing fossil fuels with renewables, using resources more efficiently, recycling and other “green growth” measures won’t be enough. We need to concertedly reduce the amount of stuff we consume, even if that means having less money to buy it.

Some economists counter that we can save the planet without resorting to such economic shrinkage — the developed world is making progress on “decoupling” its growth from environmental destruction. But this isn’t happening fast enough.

The government stole my burger

To speed up the transition, degrowthers propose global government planning to reduce production and consumption of products that don’t satisfy genuine human needs, relying instead on wasteful consumerism. Hickel’s garbage pile is a sandal-wearing Byron Bay resident’s dream: “SUVs, arms, beef, private transportation, advertising and planned obsolescence.”

This is where the degrowth agenda ties itself in knots. Its approach to accelerate the pace of transition would be so unpopular with voters that it would take far, far longer — indeed, it might never happen.

Humans would live happier and healthier lives without many of these products. But most people hate being told they cannot have something they like, and lots of people like driving big cars and eating meat. As The New York Times columnist and podcaster Ezra Klein has said: “Speed is, first and foremost, a political problem.” The degrowth movement “is attacking the flaws of the current strategy as not moving fast enough when the impediments are political, but then not accepting the impediments to its own political path forward”.

Perceptions that climate action will lead to an austere, joyless lifestyle have been a stumbling block to progress for decades, which activists have worked hard to assuage. The “Green New Deal”, for instance, responds to the way carbon taxes conditioned many voters to see climate action as a burdensome expense by emphasising the creation of green economic opportunities, from jobs in the renewables sector to cheaper power bills.

In this vein, realistic solutions to the overconsumption of harmful goods include public investment to make greener products more desirable (think electric vehicles and plant- or cell-based meat) and persuading more people to adopt sustainable lifestyles by emphasising prospective gains. Heavy-handed shortcuts are likely to backfire at the ballot box.

A green recession?

The problem is not just that Western voters will complacently cling to familiar comforts — there are legitimate reasons for reluctance to jettison growth.

Workers depend on production to earn an income and consume most of what they earn. Conversely, capital owners already have plenty and they’d often prefer slower growth to preserve their advantage and the relative value of their stockpile. Without unprecedented coordination, shrinking the economy could exacerbate inequality — like ordinary recessions do.

Most progressive policies also increase growth by giving more to those in need — who spend it. Perhaps the only sustained reduction to inequality in human history (in the postwar era) was achieved not only via unprecedented government redistribution, but also via policies designed to create rapid growth to promote full employment and strong workplace activism.

Conservative politicians promising “jobs and growth” are usually lying. Since the 1980s, governments have deliberately slowed the economy to disempower workers and protect companies from competition. Degrowthers appear to accept conservatives’ claims they’re the best growth-creators and thus reject the concept, rather than simply refuting their spurious economic credentials.

Degrowthers insist they only want to decrease the purchases of wealthy people and nations. But when most people in the world aren’t wealthy, and if giving them more money produces growth, degrowthers must either abandon egalitarian interventions or do what most other climate activists do: try to rapidly make that growth more sustainable.

Growing the good, shrinking the bad

This is not to say all growth is justifiable, provided it can be “greened”. Some should simply be expunged.

GDP goes up when people buy more cigarettes, when society would clearly benefit from fewer smokers, not to mention smokers themselves. Updating our measurements of growth to better reflect human fulfilment is necessary.

And given the speed of planetary degradation, we cannot wait for a slow, business-led “decoupling”. Governments need to rapidly, forcibly shrink polluting sectors, and ensure workers and communities are afforded a just transition.

But for both political and moral reasons, we should seek to replace the economic activities we subtract with better ones — healthcare, education, public services, the arts — and make these alternatives sustainable. We should also reduce inequality and diversify ownership, so any periods of lower growth aren’t felt so keenly by the most vulnerable.

As ecological destruction rolls on, we don’t have time for distractions.

If we continue in our present fashion, there will be degrowth all right and it will be catastrophic. We cannot continue in the capitalist fanatsy of infinite growth in a finite world.

It’s a shame Hickel and others use the term ‘degrowth’, because it triggers exactly this kind of reaction. When eventually the author gets past venting his reaction, he turns out to be not so far from what Hickel and many others are talking about.

If instead we look to reduce quantity (of stuff) while allowing quality (of life) to improve indefinitely (as the rest of the living world does), and forget the GDP as a totally flawed measure of quality of life (it might well go down, but so what?), then we can sidestep these futile arguments about growth or not.

The author has the general idea – work on better alternatives as wasteful practices are reduced. Let’s have a constructive conversation about that.

I wrote my dissertation on degrowth. I agree with Hickel, Kallis etc on their analysis of the problem. On a planet with finite resources/waste absorption capacity, absolute decoupling is required to achieve endless, compound economic growth. Absolute decoupling of gdp and resources is impossible. It’s theoretically possible with emissions but not, according to these authors, in time to prevent the worst impacts of climate change. The problem is that degrowth scholars think that degrowth is compatible with capitalism. In my analysis it is not. Investment in capitalist economies is driven by confidence is future profitability. In a degrowing economy, even one like that modelled by Jackson and Victor – which contains some heroic assumptions and MASSIVE redistribution – the profit rate declines. I don’t believe the system would continue to function. Also, as Clarke suggests, there is no way on Earth degrowth will be voluntarily adopted. This is very well tread ground. It would require all of the richest, most powerful people on earth to give up their privileged positions. The vast majority of workers would also oppose it which means all governments would oppose it. The only option, as I see it, is to continue pressuring governments to reduce emissions etc and create an alternative system within the existing system in preparation for the inevitable economic and ecological crises to come.

The problem is that perpetual economic growth is virtually impossible, without destroying the ecosystems we need to survive. Perhaps if we based our economies on something beyond the mere pursuit of financial wealth……or is that too radical?

yes a well-being economy is another name for how we go through degrowth to a new steady state economy with an emphasis on well-being and not growth for its own sake

Apparently that is just radical thinking! Benjamin doesn’t give the human race much credit for knowing what is really important to them when they aren’t being bombarded with advertising that tries to convince them that all they are lacking is a new car!

I’m not sure why you think that saying people don’t know “what is really important to them” just because they are being advertised to is giving “the human race much credit”.

You can grow the economy without destroying the environment just as you can shrink the economy and destroy the environment. Shrinking the economy isn’t a silver bullet. Price the externalities, price waste properly so we move more circular, there are so many easy things we can do but it should be driven from a overarching policy level to make ‘bad’ things much more expensive

This is an open admission that conventional neoclassic market economics has no answers to anything. Firstly, wealth inequality must be urgently reversed and Piketty shows how that can and should be done. Secondly, all environmentally damaging activity must be reversed by regulation and taxes. Thirdly, economic growth must be managed to ensure the first 2 principles are not compromised. If growth produces unmanageable environmental waste and destruction, that growth is demonstrably bad for humanity. But the myopic view of economics pays no attention to externalities like human well being and social harmony. That’s why it is the dismal ‘science’.