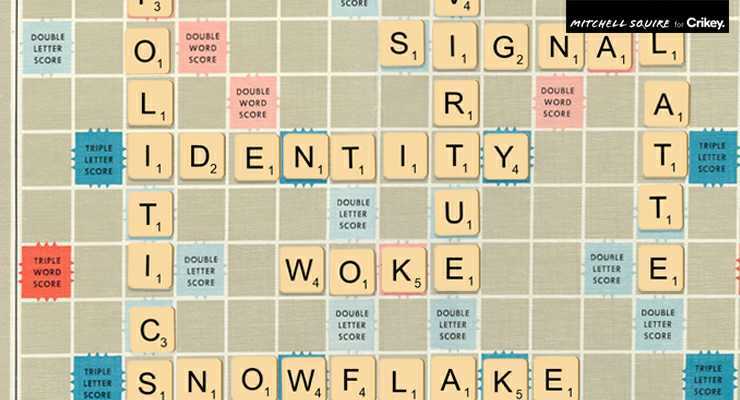

Looks like Australian and American political elites have made a one-for-one swap on slangy hot takes: they’ve given us “woke”, and just this past week political analysts in the United States ransacked The Castle for “It’s the vibe”, now popping up on American wonk Twitter.

It follows on from the turn-of-the-century political linguistic exchange when Americans gave the world’s culture warriors “politically correct” and Australia offered “the dog whistle” in exchange.

All four have one thing in common: show me you’re talking about racism (or some other discriminatory -ism) without saying that’s what you’re talking about.

“Woke” is a coward’s word — a sneaky shiv of abuse from the right or, rendered cautiously down to “not woke”, a shield of defence for the centre-left. It’s a punch pulled. A blow ducked. A hard truth evaded. A claim of defamation avoided.

Once Black American shorthand, its first defined use as “well-informed, up-to-date” appears in a glossary of “phrases and words you might hear today in Harlem” in The New York Times in 1962. Seems safe, although the heading gives its political context away: “If you’re woke, you dig it”.

It reappeared in popular culture as a recurring refrain (“I stay woke”) in Erykah Badu’s 2008 release Master Teacher. In Badu’s voice, it’s a declaration of pride in culture and learning.

It broke into widespread public consciousness through that most culturally influential use of social media, Black Twitter. (“Can you imagine the last 10 years of American pop culture without Black Twitter?” asked author Sarah Jackson in a July Wired magazine cover story, “A People’s History of Black Twitter”. Australia? Same. Take @Indigenousx.)

It became institutionally embedded in the way new words are in the English language — by inclusion in the Oxbridge university dictionaries. In 2017, the Oxford Dictionary defined it as “alert to injustice in society, especially racism”. Cambridge, more cautious, qualified further: “aware, especially of social problems such as racism and inequality”.

Too late. Too polite. By then “woke” was on the fast-track to a term of abuse — suggesting (as per the crowd-sourced Urban Dictionary) fakery and pretension. It absorbed its own superlative form: “woke” became definitionally “too woke”.

Track this devolution in the blog of Australia’s Macquarie Dictionary. Last year it offered wokefishing: “pretending to have progressive views on dating apps but not having them in real life”. This year came wokescold: “to criticise someone for not having views that are left-leaning or ‘woke’ enough”.

(“Scold” has travelled its own gendered shift from the old Norse skald — a Viking poet — through Middle English as “a person of ribald speech” to settle in misogyny as a “clamorous, rude, mean, low, foul-mouthed woman” in Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary.)

It’s hard to read the Oxbridge definitions into “woke” usage on, say, Sky after dark. When Andrew Bolt dismissed New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s “woke politics” last month, did he mean to criticise politicians for being “alert to injustice”? Or when doggerel laureate Senator Matt Canavan warned the Wiggles “you go woke, you go broke”, did he mean to challenge 60 years of marketing and entertainment strategy which sees the value of being “alert to injustice” in product design?

The right’s weaponisation has brought pushback. In 2019, US journalist Joel Anderson (creator of the latest must-listen series of Slate’s Slow Burn podcast on the 1992 LA riots) tweeted: “One word that I really wish black people had never used in public was ‘woke’. But we lost it and it’s gone now … when I see ‘woke’ now I immediately suspect it’s being invoked in service of racism.”

With one question this month — “Are Democrats too woke?” — CNN’s Dana Bash brought the debate roaring back. Serious political writers such as The Washington Post’s national correspondent Philip Bump tried to damp it down as “an appropriated descriptor that’s used to disparage rhetoric or policy that is seen as overly centered on discussions of race”.

Anderson, at least, wasn’t having it. Last week he tweeted: “If you’re not black and started using ‘woke’ pejoratively sometime post-2018 or so (or worse, don’t know anything about the earlier iteration of the term), I think it’s fair to consider it a racial slur.”

I note that the “culture wars” which are frequently evoked imply an equal battle. I know I’m a mad old leftie, but it seems to me that the culture wars basically involve bomb- throwing from the right at the left. Politically correct means civil to me. Woke means concern about the abuse of minorities or climate catastrophe. Do -Gooders are well intentioned people.The culture wars alter meaning so that positions on public policy that promote decent or humane behaviour can be abused. Tell me how or when it happens the other way. Does the left alter public debate to turn moral positions by the right into abuse?

I dont for a moment disagree that the left twittersphere can be every bit as unhinged as the right. But it doesn’t seem to be as creative in terms of dishonestly altering the public discourse. It is primarily reactive.

So my point is…can we stop talking about culture wars as if it is an equal battle? There is an offensive side – the right- and a defensive one. I wish it were the opposite way around, because the left loses every bout. But to my way of thinking there is only one aggressor here, not two.I would call what happens right wing bombardments, with only scatty and disorganised left wing defence.

Perhaps we need to fight back with T-shirts emblazoned with ‘politically correct, woke do-gooder and proud of it.’ Only partly joking. The terms of public discussion by the likes of Tudge and Dutton need to be faced down.

I love that!

Agree. The other one not mentioned in the article is “virtue signalling” as a pejorative. Usually by someone wearing a club pin or an old school tie, and shiny shoes.

As though “leading by example” were a bad thing.

I think that it’s probably all a deep internalization of Thatcher’s “there is no such thing as society”, or modern corporate laws about “maximizing shareholder value” that mean that, for a company, any activity that diverts resources away from the bottom line, such as community building or various forms of moral stance, is notionally illegal. That corporate amorality boils over into some sort of social lowest-common-denominator identification among people.

Woke seems to have replaced “Social Justice Warrior” as an insult from the right in Youtube type comment sections (mainly with American leanings). Less syllables and easier to type I am sure, although Social Justice Warrior was often abbreviated to SJW. To be fair, the left often lobbed back RWNJ (Right wing nut job).

Of course, social justice warrior can only be an insult if you don’t think about what the term actually means.

Add to that, ‘bleeding heart’. A bleeding heart is a functioning heart. If a heart doesn’t bleed then it’s either dead or made of stone; perhaps a lump of coal.

I dont for a moment disagree that the left twittersphere can be every bit as unhinged as the right. But it doesn’t seem to be as creative in terms of dishonestly altering the public discourse.

Isn’t that the truth! And when accusations by the unhinged part of the progressive twitterverse are ridiculous (think: kids Halloween costumes and cultural appropriation), at least you can usually be somewhat certain that the alleged offense actually *happened*. The right routinely gets their knickers in terrible knots over stuff they’ve made up from whole cloth (think: “you can’t even say merry Christmas anymore!!!”)

The right always wants to appropriate stuff from the left because it’s often more popular. Perhaps they should consider becoming a leftie entirely.

Like gold plated state pensions and Medicare for the LNP’s own constituents….

It can’t be denied that the Sneering Right has rushed to appropriate “woke” as an umbrella boo-word applying to anyone with views to the left of Etzel the Hun. But there’s a reason for that. Before the heist happened, the word had become associated with a specific tendency or faction within the Left which has come to play a similar role to that of Stalinism in the 30s and 40s, and which does great service to the Right by feeding it one free kick after another. It’s important that it be acknowledged and criticised (or critiqued if you must) from the Left, to make sure the Andrew Bolts of this world don’t get away with blackening (whitening?) the Left as a whole with the same brush.

The tendency I mean is confined almost wholly to the younger academic Left and seems to have grown out of Cultural and Gender Studies, by way of the dreaded Critical Race Theory which I’ll criteek another day. Ever since I had a major run-in with members of this faction last year on a previously respected professional discussion site which it appeared to have somehow captured, I’ve been curious about it and trying to tie down what it’s about and why it’s a danger to the Left. It’s certainly distinctive and coherent enough to deserve a name of its own, but none seems to have emerged, except maybe “cancel culture”, the term used by Waleed Ali in his essay in last November’s Monthly which is still the best thing I’ve read on it in Australia.

Since it’s essentially more a kind of hardline liberalism than radicalism as traditionally understood, given its primary focus on the rights of often very small minorities, I’ve toyed with “Ultraliberalism”, on the analogy of “ultraleftism”. “Left exceptionalism” is another one that captures some but not all of it. But pending anyone coming up with something better, I’ll stick to “Wokeism” as my working title.

Wokeism is definable by the simultaneous presence of seven characteristics which individually are not exactly unknown elsewhere in the Left, and found right across the political spectrum. It’s their combination – or as Wokies themselves would put it, their intersection – that makes the movement distinctive:

Identitarianism – judging people by what they are, not what they do or say. Engaging with the stereotype, not the person. Prioritising the sensitivities of self-identified outlier groups over big issues of political contention (global warming, Covid, economic inequality) that affect an entire class, nation or planet. Staying aloof from the mainstream of progressive economic thought.

Exclusivism – the belief that only an Elect who meet stringent tests of theoretical orthodoxy and demographic acceptability, and can master an arcane and constantly shifting pseudo-technical language, qualify as truly progressive.

Exceptionalism – belief that eccentric or outlier communities are exceptionally Oppressed and thereby morally superior to the general run of humanity.

Manicheism – everyone is either orthodox or heretical, Privileged or Oppressed, part of the solution or part of the problem, with no middle ground. Degrees of transgression are not recognised, e.g. using last month’s Correct-speak is as reprehensible as the Holocaust.

Determinism – Demographic determinism: the belief that people are born Privileged or Oppressed and condemned to retain that status for life. Historical determinism: historical events inexorably shape the future, even centuries later, and their effects cannot be reversed.

Contrarianism – Wokeist propositions tend to be made in ways that are self-evidently absurd on a first hearing, and often on further consideration (“If you think you’re a woman, you’re a woman”), and couched in terms (including acronyms) that are unintelligible to outsiders and difficult to pronounce or remember.

Refusal of dialogue – Playing the man, not the ball. Rational objections to the orthodoxy are never addressed directly in their own terms, but dismissed as evidence of improper motives (e.g. defending White Privilege) or imagined psychological disorders (e.g. transphobia), or else simply with the assertion that you wouldn’t be saying that unless you were right-wing. Those who differ from the orthodoxy must first abase themselves publicly before the Elect (“do the work”) in order to be admitted as allies.

Sorry, this has been a bit of a rushed thought-dump in what remains a work in progress. But I hope it’s been enough to convince at least some of you that there is indeed something here to see, and maybe to worry about.

Interesting overview of recent lexicography of political PR memes or dog whistles used/encouraged by radical right libertarians to upend objective political discourse and stability; Covidiots, alt or far right are good examples adopting existing language for dog whistles to attack themes and/or influencers of the centre.

It’s not random in strategy and tactics as explained by the expert in dog whistling, Berkeley’s Prof. Ian Haney-Lopez but purposely divisive, in ‘Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class’ (2014) while it avoids denigration of white Christian conservatives or right, and also gives the latter ammunition to fire off; worse Haney-Lopez explains that it is about attacking liberal democracy while claiming e..g ‘freedom of speech’.

Fascinating analysis, but completely lost on me – as soon as I see any of these terms used, I immediately turn off the source.

They are red flag warnings of “bigotry approaching”, and almost always from ultra right wing nut jobs.