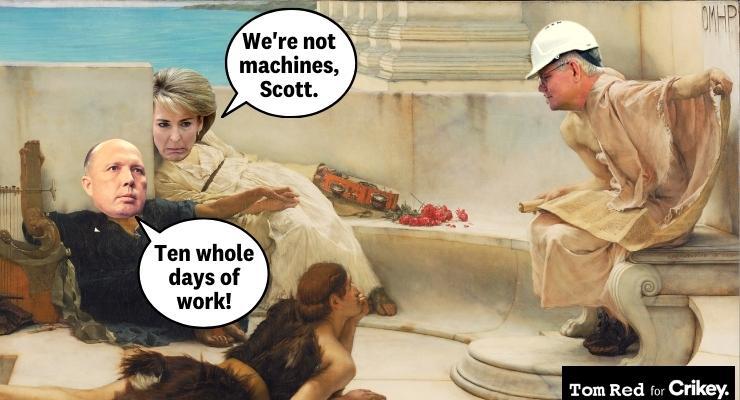

The Morrison government hasn’t had a comfortable few days in Parliament. Fortunately it won’t be spending much time there in coming months.

The proposed parliamentary calendar for 2022 released yesterday leaves the possibility of just 10 sitting days between the end of this week and August, provided the government calls an election for May. So federal Parliament will sit for just seven days in February. Then, after a three-week hiatus, it will return in late March, with a budget proposed for the 29th. Then it’s election mode.

A poll must be called before May 21, and after months of tea leaf reading the calendar is the firmest evidence that Prime Minister Scott Morrison will go in May, effectively ruling out sittings in May and June.

If he calls a May election, the Senate will sit just five times between the start of the year and August. It means election promises like a federal integrity commission (delayed indefinitely — somehow Labor’s fault), and a religious discrimination bill (deferred to a joint committee with the Liberals divided) might not be legislated before the polls.

A ‘work-shy government’

Even accounting for those sittings, the 46th Parliament will wind up being the least active in terms of sitting days since the 33rd Parliament, which lasted just a year and a half because of an early election in 1984. That lack of activity is in part because COVID-19 led to sittings being suspended in 2020. Not every comparable country did this. While Canada suspended some sittings, the UK never fully shut down Parliament, moving instead to hybrid virtual sittings.

Labor says the lack of action is a sign of the Morrison government’s parliamentary laziness. Speaking to the Nine network this morning, former opposition leader Bill Shorten said Australia had a “work-shy government”.

“If an unemployed person on Centrelink only had to do as few job interviews as Mr Morrison expects LNP parliamentarians to attend work in Parliament, the person on Centrelink would be breached and kicked off the dole,” he said.

Former Victorian Supreme Court judge Stephen Charles said the lack of sitting days had serious implications for government accountability: “The Parliament is there so that the electorate can see and hear what is taking place in government. That it’s sitting for only ten days is disgraceful.”

Of course, we could have even fewer than 10 sitting days if Morrison calls a March election in late January. He won’t yet commit to an election date, but Labor is prepared for the possibility of a March poll.

Asked about the date on television yesterday, Morrison repeated the line that “an election is due in the third week of May”. When pushed further, he dismissed election speculation as one of those distracting Canberra games he’d rather not engage in.

“People will play the political games down here in Canberra and they’ll carry on,” he said. “I’m not distracted, but our team is focused on ensuring that we secure this economic recovery, we keep Australians safe, whether it’s from the virus or the other threats we face.”

Whenever Morrison calls the election — and the impact of the Omicron variant could have a real bearing on that — the calendar means he gets to avoid those “Canberra games” and spend more time out on the campaign trail where he’d much rather be this week.

Canberra games continue

But those “Canberra games” over electoral timing are games of Morrison’s making. As prime minister, he gets the extraordinary tactical advantage of picking the date of the election at a time of his choosing, and has taken advantage of that by keeping both his political opponents and journalists on tenterhooks.

That advantage is unique to the prime ministership. Every state and territory barring Tasmania has fixed four-year electoral terms. The UK, Canada and the United States all have fixed terms.

But at a federal level, the timing of an election is governed by a confusing thicket of provisions in the constitution and the Electoral Act. The former can only be changed via referendum and Australians have voted down four times aligning the House and Senate terms, effectively creating a fixed-term system.

Yesterday Shorten reiterated his calls for fixed parliamentary terms, something he’s been in favour of for some years. But until someone bothers to lead another referendum, we’re stuck with the Canberra games.

“Labor says the lack of action is a sign of the Morrison government’s parliamentary laziness.”

Labor is too kind. The Morrison gang avoids letting parliament sit because it loathes parliament, despises its proceedings and cannot abide the scrutiny that results when it does sit. The Morrison gang would, if it could find a way, rule without parliament.

Yep…in summary laziness…and gutless government avoiding scrutiny.

Labor could just as well have left out the word ‘parliamentary’ altogether; Morrison’s government does not like governance per se, as its raison d’être is simply to keep Labor out. The daily work and longer-term planning of government merely distracts from that goal. All the tardy legislation introduced in parliament in the last week or so has demonstrated this. But in support of your last sentence, readers will surely remember Peter Dutton admitting to this in 2018, in comments to Sky News following publication of bad poll results:

Peter Dutton says he has always seen ‘parliament as a disadvantage for sitting governments’, following the final Newspoll for 2018 which had the coalition trailing Labor 55-45 on a two-party preferred basis.

https://www.skynews.com.au/australia-news/politics/peter-dutton-sees-parliament-as-a-disadvantage-for-governments/video/79f030a2d39f53806fd9c0f6233ba1e5

Modus operandi of imported US radical right libertarian ideology, shared with the UK Tories. Not just the fewer sitting days but how Parliament and liberal democracy are being, if not trashed, disrespected, strategically….. the long game is to make Parliament irrelevant or simply a rubber stamp?

Morrison is a poor performer in Parliament as are most members on the House of Reps front bench hence they are wise to avoid exposure to Question Time. In addition, the new Speaker is a major disappointment, his lack of experience is obvious nor does he have any presence or clout to ensure a smooth flow of business. One could be forgiven for thinking he’s been mentored by Bronwyn Bishop.

The more images of Parliament as a rabble during Question Time, the more the electorate will finally twig that the government is incompetent.Therefore it was essential to keep sitting days to a minimum. Frankly even ten days is too risky for Morrison.

“The more images of Parliament as a rabble during Question Time, the more the electorate will finally twig that the government is incompetent.”

It does not work that way. When the public sees parliament is no better than a cage of howling monkeys throwing crap at each other the result is contempt for MPs and for parliament, not the government. It does little or no harm to the government, that is, the ministers running the executive. The ministers can ensure their image is based on their TV and radio interviews where they can appear dignified and choose how they answer any questions, usually from interviewers they know will behave themselves. The ministers gain further benefit from the normal big imbalance between media coverage of government and opposition.

Indeed. The last thing Morrison wants is more public scrutiny in Parliament and the close second last thing he wants is for the public to see LNP backbenchers crossing the floors of the Reps and Senate. What Morrison has done achieves avoidance of scrutiny, continues to conceal the absence of any agenda other than hold power, helps to conceal current and any future LNP party mutinies, staunches the growing flow of mutineers across the floors of parliament, allows him to don the hi-vis and go full tilt at campaigning in front of a compliant and supportive media, and denies Labor and Albanese a grab from the Reps on the evening news. Winner Winner Chicken Dinner.

The problem is the ALP are even worse at Question Time. I can’t remember the last time anyone from the ALP even managed to land a glove on the Coalition.

An old saying suggests : never argue or attempt to negotiate with a crazy man or a crook. That may partly explain the low ‘hit score’ by the ALP.

The new Speaker is appalling.

Tony Burke is eating him up and spitting him out at every session.

With Smith sitting up at the back of the room and looking on, he must be so pleased he quit, or was Smith bullied out of the position by Morrison.

There is without doubt a story behind his resignation from both the position – in which he excelled after the Bronnysaurus – and his seat.

I just hope that some enterprising journo. (if that species is not extinct) has lined up Smith for an in depth interview after the next election.

Far more useful would be BEFORE the next election.

Yes that is the question.

I really enjoyed seeing Albo and Tony teach him about the rules behind standing orders/who has the call. Sit down boofhead.

The Prime Minister for Sydney at it again. ““People will play the political games down here in Canberra and they’ll carry on,”. For 25+% of the population, it’s up here / there in Canberra.

And the political games are played mostly by politicians, none of whom actually reside in Canberra.

When I quizzed a friend who grew up in Canberra why she spoke of going ‘up’ there from Sydney, she pointed out that topographically it’s higher. In this sense, the PM also misrepresents his Sydney constituents, though of course spatially is the least of the ways in which he does so.

Morrison also suspended Parliament when covid 19 first arrived in Australian and was criticized for it.

Morrison will use every trick in the book to win back office.

Unfortunately for Morrison, after three years in Office, most voters fully understand who Morrison is, what he stands for and he is also a known pathological liar with no credibility what so ever.

Morrison is finished and he knows it.

Dutton and Frydenberg are already auditioning for Morrison’s job but unfortunately for these two, they will never make it to the top either. The three of them are as useless and unappealing as each other. The three of them make Albanese look better everyday.

Peter Dutton was going on about a Labor member having a glass jaw. Says the person who threw a tanty about somebody who questioned his comments about Brittney Higgins (she said, she said) on Twitter.