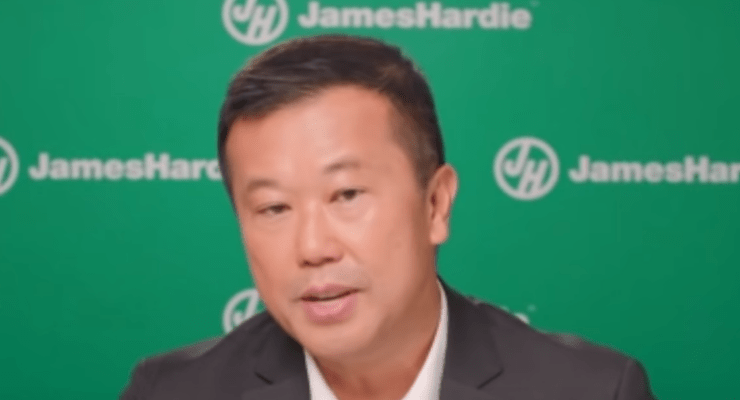

The shock dismissal of James Hardie boss Jack Truong is the latest in a series of previously unthinkable public terminations of CEOs over their behaviour.

Boards appear increasingly comfortable to not merely part with an ostensibly successful chief executive, but to disclose the reasons. It’s a trend probably inspired by the Me Too movement that saw disgraced producer Harvey Weinstein sacked from his production company in 2017. Weinstein was later sentenced to 23 years in prison.

Truong, naturally, disagreed with the allegations, claiming he was “blindsided by the accusations and unequivocally rejects the assertions made”.

Truong is clearly no Weinstein (and to be clear, absolutely no allegations of that sort have been raised). Instead, the James Hardie board interviewed more than 50 people who worked with Truong on a daily basis; 80% alleged some sort of inappropriate behaviour. It appears Truong was simply an old-school tyrant and terrible manager, not a Weinstein-style abuser.

His prior roles included 26 years with manufacturing giant 3M and heading up the United States operations of Electrolux. The US is known historically for producing harsher, less personable executives; another executive who fitted that mould was the disgraced Al “Chainsaw” Dunlap, a legendary tyrannical cost-cutter who was once hired by Kerry Packer to run his private business and was eventually jailed for accounting fraud at Sunbeam.

The most fascinating element of the Truong dismissal is its very public nature. The James Hardie board, possibly still wearing the scars of its decades-long asbestos scandal, chose to side with senior executives over the CEO. This is far from controversial and is a common reason for removing a CEO (especially when financial performance remains strong — James Hardie’s share price has risen by 363% since 2019). Executive upheaval is what led to Steve Jobs being fired from Apple back in 1985 (although he wasn’t actually CEO).

The difference now is boards appear far more willing to be honest about the reasons for dismissals. A decade ago, Truong’s firing would have almost certainly been referred to along the lines of a “resignation to spend more time with his family”.

Truong’s dismissal comes after the public removals of financially successful Cleanaway CEO Vik Bansal, Oil Search’s Kieran Wulff (albeit partially on medical grounds) and the infamous (and ultimately unjustified) removal of popular Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate. (Holgate had the reverse problem: she was fired for being too generous to senior executives.)

The key lesson from the Truong firing is that executives have two main roles. The first is to properly allocate capital, a task at which Truong appeared to perform relatively well. The second is to create and guide an outstanding team of leaders. In this regard it appears he failed.

The James Hardie board could have taken the easy option — still favoured by many boards — of a public resignation and a generous termination payment (paid for by shareholders, of course). This is what the Rio Tinto board agreed with former executives Jean Sebastien Jacques, Simon Niven and Chris Salisbury, with Jacques able to retain $43 million in equity incentives.

Instead James Hardie, led by chairman Mike Hammes, accepted potential reputational damage and did the right thing by its shareholders.

Holgate was setup, put simply. Anyone with the facts, would see the transparent nature of he fabricated dismissal, Morrison’s pathetic attempt at outrage, and Minister Fletcher’s complicity. She pushed back on the board’s desire to cut over 200 regional post offices, saved 3000 jobs, and expanded the AP business through the bank agency setup. This all goes against LNP “economic” policy of low level job decimation, regardless of social cost. Her predecessor, Ahmed Fahour, was paid $5 million a year, compared to her $1 million, and resigned with a $10 million golden parachute. He presided over the first yearly loss in AP history. Holgate’s gift watches, costing some thousands, faded to insignificance compared to Fahour’s $2.5 million spend in treating a plane load of favoured Bods, to a free trip to the London Olympics, courtest of AP funding. PM outrage, none, Ministerial outrage from Minister Fletcher, none. Boy’s club attitude, gleeful.

Fahour is behind Latitude Financial, the “buy now, pay later”, finance arm of Gerry Harvey’s operation. Could it all be labelled financially predatory, from the AP Holgate scam, through to Gerry Harvey’s retention of jobseeker funding, the $6 million of $14 million only refunded due to an AWU blockade of his outlets. Integrity, nah. Honesty, nah. Social responsibility, no way. The new world of business practice in Australia.!!

Thanks for the Fahour/Hardly Normal connection – you know it makes sense!

Half the electorate, and almost all who would shop there, have trouble remembering to zip their trousers, never mind make a payment on time especially when stretched over a year or so.

The other infamous member of the US executive diaspora is Sol Trujillo at Telstra. For whatever reason – possibly due to Australian culture being totally at odds with unearned seniority – these kinds seldom do well. Trujillo has the reputation of one of the worst performers in recent Australian executive history.

Unfortunately this does not appear to be correct. Dunlap was fired, sued by the SEC etc but never jailed.

Authoritarian traits with skills of financial management, presentation, PR, politics and persuasion do not equal leadership.

PR stunts – war games! Orgs and boards have this in the bag. Public fire, private aspire. Take a hit for the team! Disappear, reappear, magic millions. Mr Fisher’s board games. Economic poor man’s game if you are not an Actuary. Economists are second hand salesmen.

“Predictors of history”.