On last week’s Q+A, Labor’s Clare O’Neil was asked along with other panellists to respond to a questioner’s damning assessment of the prime minister’s character.

Her first brickbat was less eviscerating than we might have expected: “The truth is that Scott Morrison is the most strategic politician in the Parliament.” She followed this up with more familiar swipes: he’s a liar, he can’t be trusted, etc. But the “most strategic” line was an interesting first gambit — seemingly as much an observation by the opposition spokeswoman on aged care as an attack.

The idea of being “strategic” is now very common in public discourse. It is a quality often viewed in positive terms, though not by all. In the knowledge economy it has become a prized, saleable commodity. Thus management consultancy companies such as EY and McKinsey advertise their wonderful expertise in such arcane areas as “strategic innovation” or “strategy capacity and design”.

It has been an interesting development in Australian politics that the Liberal Party now enjoys particularly close ties with this industry; a number of ministers began their careers there — among them Angus Taylor (McKinsey), Alan Tudge (Boston Consulting Group) and Michael Sukkar (PwC). And as Crikey has documented, such firms have found themselves in recent years the fortunate recipients of increasing government largesse.

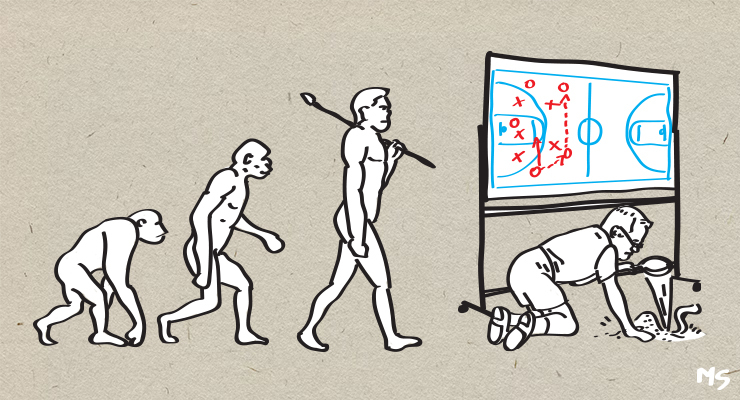

The ever-expanding embrace of strategy as a part of professional — even personal — life is the motivation for academic Lawrence Freedman’s epic work Strategy: A History. For most of its history, Freedman records, the strategy idea was confined to military domains — first documented informally in the works of classical writers like Sun Tzu and Homer, and then formally in Clausewitz and other military theorists in the 19th century.

A dramatic shift occurred in the 1950s and ’60s, Freedman notes, when the concept was adopted wholesale by US corporations, both as a response and a catalyst for an increasingly competitive business environment. From there the idea of strategic thinking has spread virus-like into virtually every area of human endeavour, including modern politics.

For Freedman, “strategy” has several defining characteristics. In line with O’Neil’s observation, it is interesting to see how these square with aspects of Morrison’s career.

The first characteristic is that strategy is always adversarial: “It comes into play in the face of others who might frustrate one’s plans,” Freedman says. The big “other” in Morrison’s world right now is, of course, Anthony Albanese, but those who would frustrate his plans now take in a vast array of personnel. Significant “frustraters” in recent days have been the entire rank and file of the NSW Liberal Party, who as a result of Morrison’s extraordinary tactics find themselves cut out of any meaningful participation in the electoral process.

We have also learnt recently about the low strategising employed by him to seize preselection in his seat of Cook, almost destroying the life of his opponent Michael Towke along the way.

It is the highly adversarial approach of the PM that has led Labor to dub him “divisive”. On his own side of politics, it has provoked a much more colourful array of descriptions: “ruthless”; “horrible”; “a bully”; “an autocrat”; “unfit to govern”; “a complete psycho”, etc.

Strategic action also has a short-term element. As Freedman explains, it requires a constant and ready adjustment of approach. The accomplished strategist, he notes, is always “fluid and flexible” in response to changing circumstances and objectives.

Sean Kelly in his recent book The Game: a Portrait of Scott Morrison picks up on this aspect of Morrison’s actions: “He will do whatever needs to be done at that precise moment in time.” For Kelly, this weddedness to short-term strategising goes a long way to explaining not only the PM’s regular shapeshifting on issues — suddenly refugees are released — but also his highly problematic relationship with the truth: “[Morrison] never feels in himself insincere or untruthful, because he always means exactly what he says; it is just that he means it only in the moment he is saying it. Past and future disappear.”

It is this tendency in the PM that Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells may have had in mind when she spoke of a man with “no moral compass”.

In understanding the world of strategy, Freedman says we need to distinguish it firmly from a related concept: planning. Planning is long-term oriented. Unlike the more ephemeral nature of strategy, planning aims for continuity and coherence through “a sequence of events that allows one to move with confidence from one state of affairs to another”. In government, this is in effect about the development of policy and also the methods by which a policy might be implemented.

In the last election, Morrison was criticised for being virtually a policy-free zone, yet the strategy reaped dividends for him. The early signs are that this campaign will be not much different. A regrettable consequence on the Labor side is that the evident advantage of being policy-free has forced a very slender ALP platform this time — though policies, at least, there are.

From Morrison’s biography, it is easy to understand why the PM is a strategy man par excellence. The advertising industry, where most of his early professional life was spent, knows only one essential mode: the marketing strategy. The position of party president, a role Morrison occupied in NSW in the early 2000s, is also largely a strategic one. But there are larger, ideological reasons — beyond life experience and character — that explain the broad approach, both his and his government’s.

The Liberal Party’s unshakeable embrace of its neoliberal, small government agenda over the past two decades has seen a progressive stymying of any desire to plan for the long term — think no further than climate policy. And its shredding of the public service over this time has also meant that, even if it did entertain serious policy initiatives, there is now scarcely the capacity for any such reforms to be carried out.

What’s left inside this hollowed-out version of government is little more than a laissez-faire approach to the economy, along with the highly strategic doling out of taxpayer funds to targeted sections of the country. In the absence of policy and planning, there is only strategy.

Elections operate in two time frames. There is the short-term of the campaign, and then there is the longer term of how the country might be run over the ensuing three years and beyond. Like the government, much of the Australian media is now captivated by the short-term and the strategic: “Who won the day/week?” “Who made a strategic blunder in a reply to a question?”

One goes into the campaign pessimistic about anything resembling adequate coverage of the country’s longer-term needs and prospects. On this score, the first days of the campaign — and the frenzied media pile-on over the Albanese gaffe — confirm one’s worst fears. All this will play well for Morrison, where the alignment between his methods and the media’s interests seems almost complete.

Freedman’s final word on strategy could have been written with Morrison in mind: “Strategy is the central political act. It is the art of creating power.” And in Morrison’s case, do whatever is necessary to hold on to it.

“Do whatever it takes to hold onto power”.

Yes, I think you have nailed it there.

The question then is “What is he going to do with the power?”

Unfortunately the answer is “Look after his mates” and loaf about in Kirribilli House.

Now is that good value for our money?

Thanks Tim, what you write is somewhat disheartening, mostly because it rings true.

You can also observe that no amount of valid criticism of ABC journalism on Twitter leads to any self-reflection of the woeful state of their craft as they struggle to copy the Murdoch propaganda.

If Morrison is strategic about power games he certainly has no strategic planning skills when it comes to managing critical issues confronting the population. He is inherently a bully if that is strategy

Yes, while the article describes someone who’s strategic in a limited sense, it actually more fully describes a psychopath. That is, a morally bankrupt individual, who has absolutely no qualms about doing whatever it takes to attain power, but not particularly interested in using that power constructively. In fact, doing whatever it takes to attain power, actively works against using it constructively. The backstabbing, the dishonesty, the manipulation of others, all tend to create blowback, because people don’t like being lied to or shafted. So to fight against this blowback, the psychopath creates a new series of lies and manipulations. And on it goes in an increasingly vicious circle: until the psychopath either gets promoted upwards, or ends up in jail.

Agree. As I read the article, I found myself wondering: strategist? or pathologically-lying amoral sociopathic personality?

‘…All this will play well for Morrison, where the alignment between his methods and the media’s interests seems almost complete…..ly planned.’