“You can have any flavour of soup you want, as long as it’s chicken or cauliflower,” one of the kitchen volunteers says through the long serving hatch — a serving hatch! — of the Burnie senior citizens club kitchen.

The place is on the edge of the CBD: a squat building, near the freight rail lines, in the shadow of the still-standing metal chutes and chimneys, the rusting factories, the red-brick and white moderne-style mills climbing the low mountainside. The polished, brown, gold-lettered boards recording past presidents look down from bare brick walls on Laminex benches, stacked chairs and, at the back, dust-over-covers, full-size pool tables.

There’s 60 senior citizens here today. “Let me remind you that anyone over the age of 50 can join our organisation,” the current president boomed in a voice which might have once echoed across a factory floor or regional bank branch. And — hang on, age of 50? OK, 61 senior citizens here today.

Check shirts and grey slacks from Best & Less, pink leisure-wear tops, beaded, with a kitten pic, and on the bottom left, the club bourgeoisie on one table, red dress suit and ironed-T, the progressives on another, a union jacket, pressed denim shirts. Me and the Burnie Advocate up the back, the whole press corps.

Labor crowd, a Labor town, but every vote counts in Braddon, and local candidate Chris Lynch is blitzing the north coast to try and unseat sitting Liberal Gavin Pearce. They are both big, bald blokes who stare out from their posters like they’re about to ask you to step outside, settle this like men, etc. It’s tough on the north coast.

Here today, shaved-headed, powerful in a business shirt and red tie, Chris “Rock God” Lynch — the nickname is from a youth spent as a travelling rocker and live band mixer; he looks like the bass player from Cosmic Psychos, and may well be — is making aged care the focus of his campaign. Julian Hill, Labor MP for Bruce, a young, neat man in an electric-blue suit and open-necked white shirt, is here to talk about the Indue cashless welfare card.

Senator Anne Urquhart, big glasses, one of Labor’s few unionist MPs from the shop floor (she led strikes at the Simplot vegetable-canning plant, in a time when the town echoed with a couple dozen factory whistles every grey morning), is walking the floor again, passing soup around. “Chicken or cauliflower?”

The speeches were perfunctory, even mild. Lynch: I went away, came back, love Tasmania, northern Tasmania, north-western Tasmania, this bit of it, pensioners built this country, got to get manufacturing back, Labor is makers … it had a delicious tang of the ’50s about it.

Hill came on, school-teacherly, starts up, “OK, well, what is the Indue welfare card?”

“It’s a con!” someone yells. It is not going to be a tough audience.

Ten minutes later, he wound up. “Well, it’s over to you…”

Union Jacket stood up. “I worked in aged care. Let me tell you about maggots.”

I studied Lynch’s and Hill’s faces, which fixed immediately. Oh, this was going to be gooooooood.

Union Jacket then gave a spiel, righteous, illuminating, enraging, but involving so much bodily waste, maggots, all orifices, bedsores, the sub-minimum wage, and maggots, that I will not reproduce it here. The urge to laugh hysterically bubbled in me. Hill, looking like an art school lecturer c.1985, might have felt it too, but held his nerve. It has to be said that through all this grand guignol the wet clank of spoon against bowl and the steady slurp did not cease. I mean, come on, it’s free soup.

There were many intelligent questions — if anything they were to the left of Hill, damning Indue, a financial services company, as a parasite. “Well, uh, they’re a company who do other stuff which is fine, they just shouldn’t be running a cashless welfare card,” he said, watching the Advocate reporter’s pen dance across a notebook page. But, ah, one is here for the off-message stuff.

“How much of my money is this card going to take? One hundred percent?” A gruff, hard-faced Scots type barked, from beneath a halo of faded red hair, like heather on stone.

“Eighty percent.”

“So it’s 80% communist.”

Hill’s mind whirred like a workshop dynamo, you could see it go — considerably faster than his leader’s the day before — as he considered how to talk about a state pension being sequestered by a private company. Indeed, Indue is behind Fupay, the microloan company that will allow you to borrow money for bread and milk and other essentials. As the new name suggests, they’re not even hiding the evil now. “Well, that’s one way you could put it. I’d just say, whatever we call it, it’s morally wrong…”

From the other side: “Is it currently only Aboriginal people on the card?”

Lynch and Hill traded looks. You take it. No, you take it. They mentally gamed out where responses would get them.

“Well, it’s about regions. It was tried in certain regions, and now they want to roll it out…”

Labor is on a winner with the Indue card, across northern Tasmania and elsewhere. Pushed, by Alan Tudge (a protégé of Noel Pearson), to curb self-indulgence in self-destructive behaviours, an area of Tudge’s expertise, it’s a live-wire issue in Braddon, which has some of the highest disability pension rates in the nation. A few stray remarks from IPA-oriented types that it should be extended to all aged pensioners has taken it, in terms of Lynch’s old profession, up to 11.

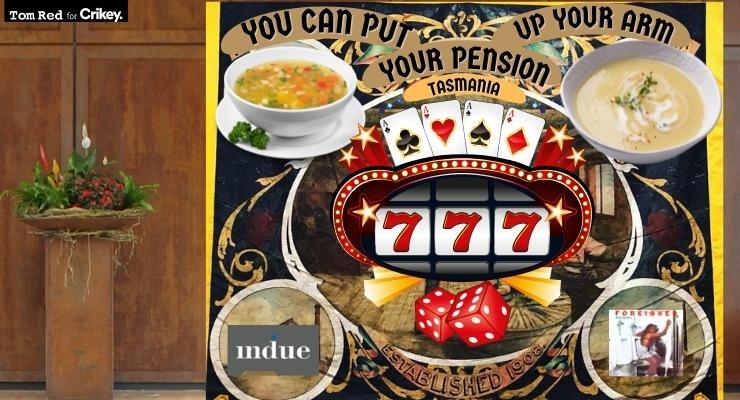

These decent, abstemious, hardworking people, I thought, broken on the machine. “I reckon everyone should be able to have their pension and put it in the pokies,” an aged slacker was saying, Ray-bans and thin cheeks. “If they wanna spend it at the pub, put it in their arm.” He actually mimed shooting up, into the sleeve of his battered 1982 Foreigner tour jacket — and there was a pause, and Hill said “OK, yes let me talk about some other features…”

Man, I would like to see that scene done as a 19th-century trade union banner, all burgundy tassels and Gothic lettering, and etched out in lace-point, the Ray-banned dude who’s been punching “Another Girl Another Planet” into the hotel jukebox for 45 years, miming putting the works into his arm. “YOU CAN PUT YOUR PENSION UP YOUR ARM!” Parade it through the high streets of the state and nation. There’s your vision, m’colleague Keane!

Vincit, O Burnie senior citizens club.

There was no shortage of love for Team Labor here, though I was surprised by how mild the pitch was. I guess they know their audience — but then, that’s what we’re all guessing about Labor at the moment, and by guessing I mean, of course, hysterically praying. Mr Scots-Granite struck me as the only real waverer, but I had barely got out “I’m a journalist…” before he held up both hands in refusal, his face shadowing like a mountainside. I bet he was some engineer once, a stalwart of the Free Church, fighting those SDA communists on the shop floor.

Otherwise, there wasn’t a declared Liberal in the house, and the only question everyone responded to was: What do you thing of Jacqui Lambie? Seems you could have any answer you wanted, as long as it was “She fights for us” or “She’s out for herself”.

“She says what she thinks! I love that about her!”, said a delicate-featured, elfin woman, a medical administrator here for 25 years (“I’m a blow in!”). “Will you vote for her?” “Oh no, I’m Labor. But I do love her!”

“She started out for us, now she’s for herself mainly,” said a sharp, sceptical woman as I pulled a chair up to the Laminex and sat down. She’d been in aged care, and was now a carer, here with two friends in wheelchairs. It has to be said that the place had a touch of the air of Beckett’s Endgame about it. Less, just life, than life here, a world of industry, its denizens thrown on a scrap heap, our world in miniature.

“She got that housing debt wiped,” someone else says.

“Did that do anything?”

“Oh yes, they’re building public housing here. They haven’t for 20 years.”

“Was that the debt thing though?” Several years ago, Lambie demanded, and got, the waiving of $150 million of housing program debt to the Commonwealth, which had cost $15 million of Tasmania’s pitifully small $28 million annual social housing budget.

This saving has gone into building 15 new units a year, in a state with tens of thousands under extreme rental pressure. Part of the deal, or maybe a free kick, appears to have been a specific mention of the interests saving in the Tasmanian government’s budget publicity.

By comparison, Tasmanian state government revenue was $7.25 billion in 2020-21. Lambie’s vote in return? For $158 billion in tax cuts to the rich. She hardly got a new deal in return. The debt write-off — a ledger move — should have been the start of the deal, not the end of it, even assuming high-income tax cuts were good for Tasmania in the first place. Did it really shift many units?

“Yes! It did!”

“She’s for herself,” said someone else.

“So you won’t vote for her?”

“Oh, I’ll vote for her.”

You can have any flavour, as long as…

Most had left, Chris Lynch and Julian Hill had gone, on their way to an identical gig in Devonport, Labor’s slow train clanking on. The rest of us stragglers now playing out the day.

“There’s still some soup, if you’d like,” one of the tireless volunteers said, hovering over the table.

Why not? Here we all are, with our faded music and dreams of the workers’ paradise, the “old people” who once looked as ancient as trees, out of a time of factory whistles and swing shifts, hundred-car freights, the all-day echoing rumble of coal down chutes into ship holds, on the oil-stained shorefront, the shops all under known names, the bustling Saturday mornings and the church-filled Sundays, the union dances and company picnics, falling back into sepia in the photos in cafes all entire and of themselves, under a slate-grey sky, and all of them now only 15 years ahead of us. Here we all are. And there’s soup? Halfway through that first week, why not?

“Thank you, yes.”

“Chicken or cauliflower?”

“I think just stick it in my arm.”

Thanks Guy, more observations from the campaign trail please.

That’s a lovely bit of writing, Mr Rundle. Tassie is a bit of a time warp and there’s no space-time region of it more warped than the NW coast. I’m glad to seeing you channelling the vibe. Wanna lay a bet on the first tattoo joint to embroider ‘You can put your pension up your arm’ on some Burnie resident eligible for membership at the Senior Citizens Club?

“Rusting factories ” is such a tired trope it’s old enough to claim the pension.

Have a look at the west coast for space/time hilarity

The urge to laugh hysterically bubbled in me

Me too, when I read this piece.

Thanks for the insight, Guy. It was interesting to learn of the division re Lambie.

wonderful, hard-crafted stump reportage, as always, chrs