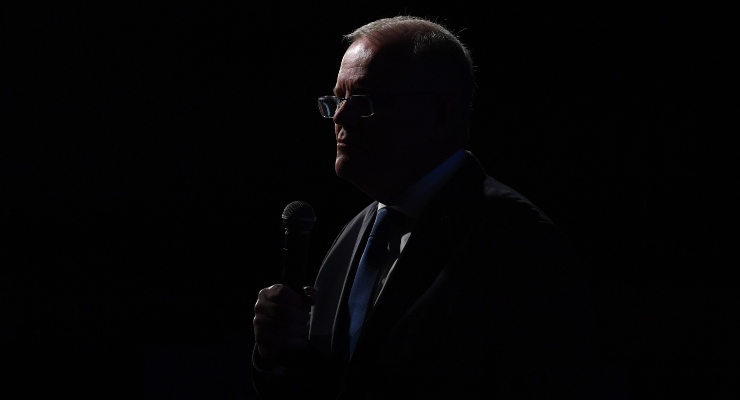

This is supposed to be Scott Morrison’s time to shine. The man who won the unwinnable election is back in his natural habitat on the campaign trail. Every day, the prime minister seems to relish leading a bus of disoriented reporters and camera people to multiple carefully stage-managed photo opportunities while unencumbered by the distraction of governing.

Last election, he made a miracle happen. Morrison, in signing up for a monster six-week campaign, bet on his ability to make it happen again: “I’m going to lead, and I’m asking you once again to follow me to election victory,” he promised the party room in February.

Except, it’s not happening. If you go by any of the major polls, Scott Morrison and the Coalition are stuck well behind Anthony Albanese and the Labor Party. If anything, they’ve lost a tiny bit of ground. Other than a dip and then a return in approval for Albanese after the first week’s gaffe — a weakness that Morrison pounced on and prosecuted — national polls show that things remain remarkably consistent at a time when polls usually tighten.

This matches the campaign we’ve seen so far. Weeks ago, we wrote that Morrison and the Coalition were running a disaster reelection campaign. While some of the more odious elements, like Katherine Deves, faded from the fore, big events like the Solomon Islands-China pact and rising inflation and rates have blunted the government’s traditional strengths. Instead, we’re seeing the myth of Scott Morrison, political genius and expert campaigner, evaporate in real time.

In 2019, Morrison snatched a victory from the jaws of defeat. He took a Coalition in shambles, with exposed divisions and a controversy-riddled frontbench, and hid it all behind an inflated caricature of himself: Scott Morrison, Sharks supporter, curry cooker, the everyman PM. He was able to claw back some approval in the lead-up to the election. In the opposite corner, his opponent Bill Shorten was unpopular and promoted big, divisive policies that fed into potent attacks against him. Morrison’s win was so unexpected that it earned him a reputation as a political genius.

Since then, Morrison has been largely an unpopular leader barring one major event. Soon after the bump that comes with winning an election, Morrison’s approval sank over his management of the 2019-2020 bushfires and lack of a legislative agenda to speak of.

Then came COVID-19. The pandemic was a disaster that provided Morrison with a political gift. It was something for the government to do. With Morrison at the helm, Australia dealt with COVID-19 better than most other nations in the world. In turn, his popularity immediately spiked larger than any other nation’s leader. According to Morning Consult, which polls the approval of dozens of world leaders, his net approval went from -27 at the start of March 2020 to +30 at the start of May. Since then, however, his popularity has been in free fall to the point that he’s almost back where he was post-bushfire season.

Today, Morrison is less popular than Malcolm Turnbull was when he scraped back during the 2016 election. He’s even less popular than Bill Shorten was when Morrison defeated him during the 2019 election. You have to go back to the 2013 election to see a leader win an election who was less popular than he is now — and that was Tony Abbott winning over even more unpopular incumbent Kevin Rudd.

Even in the first weeks of the election campaign, when it was clear he was in a bad position, Morrison was spoken of as the Coalition’s greatest asset. After all, election polls are nice, but as the aphorism goes, the only poll that counts is election day. In political reporting, elections are a referendum on a million decisions but none more so than the prowess of a party’s leader.

The press gallery’s begrudging respect for the way Morrison plays the media game also had a role in the optimism for his campaign. After all, how can you not admire an unlimited stamina for activities for the camera and his incredible shamelessness and discipline that lets him hammer a message home?

Perhaps this makes a good campaigner in the technical sense. But what about campaigning in a way that wins elections? Morrison has chosen to place himself at the centre of the Coalition’s reelection campaign, repeating his winning strategy in 2019. At time of writing, media monitoring company Streem has Morrison as the Coalition’s leading spokesperson by featuring in 63% of the coverage, with the next closest figures Josh Frydenberg (8%) and Barnaby Joyce (5%) far behind. The only problem is that Morrison is a lot more unpopular now and he’s competing against a more popular opponent. Meanwhile, the prime minister’s brand is so tainted he can’t even go and defend former Liberal strongholds.

The Coalition’s desperate attempt to neutralise this sentiment by saying “you don’t have to like him, but you need him” runs into the unfortunate reality that Morrison’s defining moments as prime minister are associated with shirking responsibility or bungling efforts. It’s telling that Morrison spruiks numbers but rarely points to a decision that he and his government made as proof of their credentials.

It’s clear that Morrison and the government believed the myth, too. Cast your mind back to the end of 2021. Back then, there was talk of Morrison calling a snap election. Instead, the government chose to wait and hope the Christmas break would give them a chance to reset. This year has essentially been their five-month election campaign, with only a few days of Parliament and using the budget as a set piece.

Morrison and the Coalition sized up Albanese’s Labor Party and bet the house on being able to outmanoeuvre and out-campaign them. So far, they’ve failed. They’ve gone backwards. This is the part where it would be remiss of me to say “anything can happen in the lead-up to election day”, but even if the Coalition was to somehow scrape a victory, Morrison’s halo is gone. All he can do now is pray.

The Australian Government stuffed up the Covid response “it’s not a race” the States were responsible for how well Australia performed in spite of the Smirko’s and Josh’s efforts.

I was going to say that. Because it’s true. Morrison did what he always does, find something that went right, appropriate it & take the credit.

Management of Covid also involved the National Cabinet Committee, which has no legal standing per se and yet whose records Morrison refuses to release.

I don’t agree that Morrison has any great talent as a campaigner. If he behaved exactly the same way but was the Labor leader, the Murdoch press would have a field day with him.

This is absolute truth.

You could pick any number of the coalitions mistakes, and put the exact thing under a labor government and watch the news-corps media decimate them. Compare the outrage of 4 deaths in the pink bats ‘saga’ (which was more about shonky small business people then labor) and the 800+ deaths in the age care fiasco that was directly caused by LNP mismanagement. Do we hear even a word??? No instead we get from Scomo, that he saved 40,000 lives.

Even larger is the 38,000,000,000 (Billion) given to companies making a profit during covid. I mean this is incompetence on a scale unimaginable, and there is barely a whisper about it. If labor had done this you would hear about it every day, and then for decades to come, and yet all we get is “everyone knows that a coalition government is better economic managers.”

Truly we live in an alternate universe when listening to the majority of the MSM. They are, quite simply, insane.

“Even larger is the 38,000,000,000 (Billion) given to companies making a profit” …

I wonder if this is something the ALP is saving for the final week of the campaign. After all – the general public have short memories. So come the last week – put away the air rifles and being out the machine guns ?

Josh from Accounts opponent independent candidate Monique Ryan used that $38B to good effect in their debate.

She was absolutely devestating on the misdirected Jobkeeper funds. 115 million to Crown and zero to public tertiary institutions who employ eight times as many. Public hospitals starved of funds during the pandemic while Gina Rhinehart’s old school in Perth (where there was effectively had no covid, no learning from home, claimed 4.8 million). She said there was a lack of transparency in the way the program was conducted and it had been difficult to find out where the money went. The Berg looked down at the lectern.

Let’s hope!

The ALP likely won’t mention it because Albo has already said, if my memory’s not playing tricks, that they won’t be asking for the firms to return the dough. I don’t see how he can make an issue of it now, but hope I’m wrong.

I really hope people remember all the massive corruption and incompetence. The Pink Batts was a disgrace ( did they actually have a Royal Commission??) – no comparison and no apology. These Liberal religious fanatics really are horrible human beings!!

This myth is on a par with Barnaby Joyce being “Australia’s best retail politician.” I think this means people not interested in politics once found him mildly entertaining.

No, I think that it means he is for sale.

I could never see that one – believable only by country bumkins

…unfortunately he’s still quite popular in the regions…Farmers aren’t fans but Tradies like his maverick style and this gives them a rural identity to go with their snorkeled 4WDs …don’t know many women who like him except the old rusted on CWA types… trouble is there is no comparable Tony Windsor type candidate to oppose him..thats what you need.. a smart person with strong rural heritage who can outclass his ornery, good’ole boys approach…

I don’t know why any woman would like him given his unconcealed contempt for them.

https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/barnaby-joyces-other-betrayal-20180209-h0vurf.html

What does “retail politician” mean?

Does it mean that he is for sale?

Bingo. Dial-M-for-Murdoch would have painted him from day one as unsuited for and incapable of being a PM. Or even an opposition leader. Right now, the greatest failing of either party leader, disqualifying him as PM material, is being presented as two ‘gaffes’ by Albo.

It was obvious by early 2020 that Smirko would have to find something to fill the year up; he couldn’t even fill his sitting days. As you say he was lucky that Covid came along but too dumb to capitalise the way Gladys and other premiers did. The rest of us are probably lucky he was never forced to come up with policies to occupy his term, and pretend to be a leader.

Agreed, we should be grateful he had a dearth of policies. Aside, of course, from the usual bastardry towards refugees.

Has anyone asked Morrison about the Murugappan famiy’s prospects of returning to Biloela? Is Border Force already booking their flights back to Sri Lanka post 21st May? Albanese has promised clear passage back to Biloela.

Good article. But with one or two of your points I’d probably differ; this one in particular:

“With Morrison at the helm, Australia dealt with COVID-19 better than most other nations in the world.”

Morrison might have been ‘at the helm’ during that time in name, but he certainly had little at all to do with the degree of leadership and positivity that we gained during the worst of the pandemic. It was the state premiers who led, who did the groundwork, shouldered the responsibility for the quarantine and the border closures, and all the while this was happening, Scotty whined, whinged and actively sought to tear down the work of the states to open up the country. If he had actually been at the helm then, we’d have seen a much grimmer outcome with the coronavirus than we did.

But yes, good article. Except – Abbott didn’t win the 2013 election from Julia Gillard, rather it was from Kevin Rudd.

Yes, for Mr. Wilson to get this fact completely wrong is unforgivable. It is the MSM’s usual pattern to reinvent the truth to suit Morrison’s agenda because that’s their natural fit. But for Crikey it is gobsmacking incompetence and suggests Wilson’s ignorance of our recent history.

Cam has apologised and explained.

I think there’s another aspect in regard to Sc?mo’s initial popularity that may not be fully understood.

People love clowns. They’ll pay money to go and watch them. And it may be relevant to his initial popularity. But do they want to be governed by a clown? I think not. So when the penny drops (Oh my god – he actually IS a clown). then the mood changes