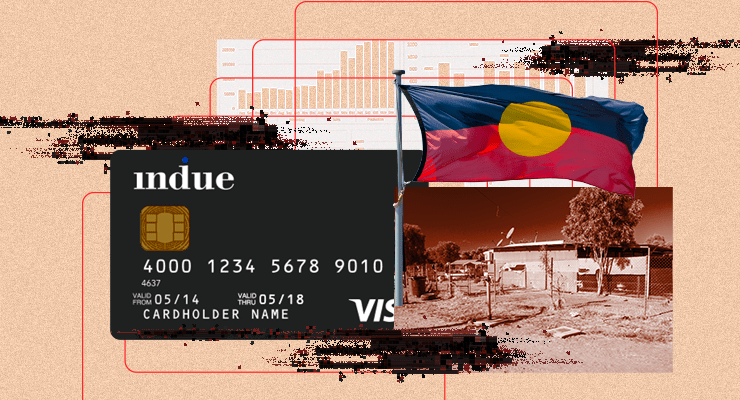

Another auditor-general review of the Coalition’s Cashless Debit Card (CDC) trial has revealed the lack of any useful evaluation of the trial within the Morrison government and an apparent indifference to establishing whether the card delivered any of its claimed benefits.

A new Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) examination of the trial — the second since it commenced in 2016 — details how most aspects of the implementation and administration of the card trial were competently carried out by the Department of Social Services (DSS) and Services Australia, but there was seemingly little interest in monitoring the trial and evaluating its outcomes.

The ANAO’s earlier report, in 2019, found that DSS’ “approach to monitoring and evaluation was inadequate” and made specific recommendations about fixing that. This follow-up report reveals virtually no useable evaluation was ever carried out, despite the trial being expanded and extended.

The ANAO’s summary reads like a checklist of failure on any effort to determine if the trial achieved anything. “Internal performance measurement and monitoring processes for the CDC program are not effective. Monitoring data exists, but it is not used to provide a clear view of program performance … The CDC program extension and expansion was not informed by an effective second impact evaluation, cost–benefit analysis or post-implementation review.”

The auditor-general went on:

“Although DSS evaluated the CDC Trial, a second impact evaluation was delivered late in the implementation of the CDC program, had similar methodological limitations to the first impact evaluation and was not independently reviewed. A cost-benefit analysis and post-implementation review on the CDC program were undertaken but not used. The recommendations from Auditor-General Report No.1 2018–19 relating to evaluation, cost-benefit analysis and post-implementation review were not effectively implemented.”

DSS did make some efforts to undertake some form of evaluation. There was data collected for internal monitoring, but its value was limited because there were no targets or performance indicators developed. When DSS did develop performance indicators, one of them wasn’t properly measurable. A second attempt to evaluate the trial, by the University of Adelaide — whose researchers warned DSS of methodology problems — was 18 months late, didn’t fix problems identified in the first evaluation, and was never used in any policy development or advice.

When the trial was expanded in 2018, the legislation implementing it specifically required that evaluations of the trial be themselves subject to independent review, which would be tabled in Parliament — thereby giving the impression there would be some rigour to the evaluation process. Even though its contract with Adelaide Uni indicated there’d be an independent review, and even after the DSS executive approved a review in February last year, DSS simply decided to ignore the legislation:

DSS subsequently decided that it was not required to undertake the review because the evaluation was commissioned in November 2018 prior to the commencement of section 124PS of the SSA Act in December 2018.To date, no independent review has taken place.

The Morrison government also agreed to implement a cost-benefit analysis (CBA) of the trial. DSS hadn’t bothered to carry out a CBA when the ANAO first looked at the trial. Eventually, after repeated delays, DSS got around to it in 2020, and last year a consultant furnished an analysis that noted extensive methodological difficulties but suggested the benefits outweighed the negatives. But DSS decided there was simply not enough robust data for the analysis, and declared it “of very limited value”.

There was also supposed to be a “post-implementation review” but that, too, suffered endless delays and has never been finalised.

Throughout it all, despite the complete lack of any evidence about the outcomes of the trial, its benefits, or how it was implemented, the Morrison government proudly announced extensions and expansions of the trial, making unfounded claims such as “evidence shows that the Cashless Debit Card works” when no such evidence existed.

What’s noteworthy about the CDC experience is the extent to which both the Coalition and its bureaucrats in DSS went out of their way to give a gloss of evidence-based policymaking to a policy primarily aimed at Indigenous Australians — calling it a “trial”, legislating for independent reviews of evaluations, claiming that expansions were backed by evidence. The ANAO, instead, has revealed at best indifference to the idea of establishing a rigorous evidence base and, in the deliberate evasion of legislative requirements, perhaps something more sinister.

It’s another example of both the politicisation of the public service and a hollowing out of its policy capacity. Glyn Davis has a monumental task to fix what used to be a respected public service.

Wow. This ought to be getting huge attention because Keane is right to say it shows ‘both the politicisation of the public service and a hollowing out of its policy capacity’. It is almost certain this is merely one example of a rot affecting far more of government than just this part of the DSS. It could hardly be of more public interest; though it does not follow that the public is interested, unfortunately.

The consistent pattern of blatant cynical lies about the program from the government for years is really troubling. The phrase ‘evidence-based policy’ is used as a marketing slogan without any regard for its meaning. An honest government could have said this was ‘faith-based’ or ‘prejudice-based’ policy and not pretended it was making any effort to gather data or evaluate it. Just how much of the government is run this way?

Wish I could vote more than once for your comment Rat, well said.

“Evidence based” always makes my hackles and suspicion rise.

Unless they follow that statement up, with the size and type of studies, providing the so called “evidence”.

Obviously the Audit Office got its budget cut for questioning the vindictive menacing wallpaper and his “Taj” sporting clubs and so the Indue card wasn’t front of mind,

The “Evidence based” statement could be based upon a bag of dog poo, load of horse dung, John Barillaro’s complaint/s to the NSW police fixated person’s unit or a long lunch with accountants and lawyers from one of the big firms seeking another income stream.

The importation of all that is the worst of the US society, with foundations spent at whim. instead of paying the right anount of tax and royalties and feeling no obligation to contribute to the national wealth and the nation’s populations well being and certainly no tangible evidence of a commitment to helping the Indigenous population find their way between the two worlds.

But there is clear evidence it did achieve its objectives: Indue (the Liberal-linked mob who ran it) were paid $10,000 pa per person (at least initially). Win-win for the racist, welfare-bashing LNP government and their Liberal mates. Great welfare system for some!

If the government could afford to pay $10,000 per card per year, that

money could have served a better purpose by upping the rates of those

that were on the card. I’m sure tge extra money in their bank accounts

would have made a huge difference in their lives by $192+ per week.

Now, if they get rid of those demeening cards and split the money saved

between social services beneficiaries there would be a nice little rise in

the rates for all, and it would be better use of that money – I’m sure Forrest

has more than enough already.

Yes, that is far more credible as the scheme’s true objective, though we might add the satisfaction some get from seeing misery and humiliation inflicted on the vulnerable. I’m not sure how that could be measured, but if it could be quantified it would go some way to making the policy evidence-based.

It would be handy to have a comprehensive summary of all the public funds poured into the pockets of L/NP mates for no discernible public good, because the Indue Card is far from alone. For example, the various

parasitesproviders who are richly rewarded for pretending to provide welfare-to-work services. It could be a rather long list.Well fellow swimmer, I think we be in sight of dry land.

The Indue card ensured that kids who had their parent on that card could never go to school with the correct uniform and all their books.

I am sure that the management of the Indue card consider it working a treat for them.

I know that this statement contradicts all the motherhood statements about “welfare” money management and the control to prevent it being spent on anything but essentials.

As the third daughter of a farming family, I never once got a new school uniform/ hat/ blazer.

Mine were all hand me downs from my two older sisters ( taken up because i was shorter), most of my sports uniforms were too. My only brother followed me and so, he had new everything as far as uniforms were concerned

The indigenous kids who camped for part of the year on our property (the tribe was still migratory until the 70’s) also followed on with uniforms/ books/ shoes until they looked tired and then they were replaced.

My mother and a couple of other landowners pooled all resources to ensure our tribal kids went to school with all the kit.

I got new shoes and socks and underwear and if any of the texts had changed between my elder sister and I, it was bought too along with stationary, pens and other essentials.Some of my cousins ( tribal or not) got pairs of school shoes barely worn because growth spurts occurred inconveniently.

Anyone on an Indue card can not pay cash for second hand textbooks or uniforms and other than the Smith family I see little evidence of the waste not era or the robustness of our old school uniforms.

From my observation post as a still working, middle class grandmother, the Indue card seems to have been another stone in the shoe of the kids that need a lift up not a push back.

An early report claimed $12000 per $14000-p.a.-earning recipient. Only an 85% administration fee. That’s the efficient private sector for you.

Of course, it was intended to be a money laundering scheme: taxpayers -> government -> Indue -> donations to the LNP.

To be fair, later reports average the payment to Indue over the whole duration of the scam since 2016 at $1,200 per person per year. But when you factor in the known extra costs to the bureaucracy, well over $100 million (that we know of) has been spent administering it. There are undoubtedly other hidden costs. So your description of it as a money-laundering scheme is accurate.

Really???

Well the Indue card is a privately run card controlling the spending of welfare recipients.

The company which runs and manages this card has people like Larry Anthony (LNP) and other leading lights from LNP ranks and ages.

They charge the government a setup fee for each card, an account keeping fee and a transaction fee and so, creaming about 1% off the top of the federal government welfare (mostly the powerless aboriginal groups) spend is a neat little earner for a debit card, which can have no bad debts and the stores which accept Indue also pay a fee for the service.

This setup, was sold down the line of restricting money used for drinking and gambling and making sure that there was money for food by limiting cash.

How can you buy fresh food at a market without cash? How can you buy second hand clothes, shoes without cash?

The people on the Indure card are forced to buy from only accepted stores…….

Follow the money! Who gets paid day in day out and where do all the profits from Indue go?

Money for nothing…………

what? Please explain!

ouch!

This is no surprise given we remain a colonial settler state. We do paternalism so well, and clothe it as care. If memory serves, wasn’t this another Andrew Forrest thought bubble quickly taken up by Abbott? Like with Howard and Brough’s Intervention, it is designed to continue the Frontier Wars (you know, the one we never had), and replace the missions with a plastic card.

And, as far as I am aware, Forrest has never once criticised its implementation. Great friend of our indigenous citizens!

You have heard of Green washing, Sports washing, think Twiggy and his purchase of all the PPE in WA which was shipped by air back to his masters in Wuhan.

Everything spent out of his Mindaroo foundation is tax deductible.

There have been photos of Aussie Twiggy with 2 Australian flags on the front of a stationary iron ore train ( a scoundrel always wraps himself in the flag. Brings to mind Toned Abs with 16 flags surrounding him, oh dear!)

this is why the “Pensioners on the Indue Card” issue, that was supposed to be a scare campaign, was in my opinion totally on the cards – not because it was some newly-hatched plan they were trying to keep a scret, but based on its inexorable momentum, kind of like the tide coming in….or perhaps even like a… bulldozer???

A re-elected Scummo would see no reason to halt the slow expansion of his latest weapon against the poor, indeed he would have said his election victory was a clear mandate from the Oz people on all things-Scummo…and that the Indue Card should be applied across all welfare payments.

Australia’s number one racist invented the Indue Card. His reward is stealing their resources and not paying one cent in royalties.