When people fill the streets with chants, banners and signs during this week’s Blockade Australia protests or the weekend’s Roe v Wade rallies, their goal is to draw attention to their cause.

But those protesters may not want that same attention turned on them individually. While protesting is legal in Australia, there are many reasons why you may not want to be surveilled by police, government, businesses, organisations or other individuals.

Former Flemington and Kensington Legal Centre CEO and a trainer for Melbourne Activist Legal Support Anthony Kelly said powerful monitoring may deter people from attending.

“People change their behaviour when they know it’s under surveillance,” he said. “They ask themselves: ‘Is it more dangerous for me to attend the protest, even though it’s completely lawful?’ ”

The American Civil Liberties Union said the unproven effectiveness, risk of abuse and lack of safeguards on technology like public video surveillance pose risks to individuals, risks they may want to lawfully mitigate.

As the surveillance toolbox expands to include geolocation data, facial recognition and drones, US privacy advocates have raised the alarm on the surveillance of demonstrations nationwide.

So how can you mitigate privacy risks while publicly protesting?

Your phone is an entry point for surveillance

If you’re planning to take your phone, be aware that smartphones are constantly collecting and transmitting data about you. A 2018 ABC investigation revealed that a journalist’s phone shared information with an online server nearly 300,000 times during a single week.

If you do take your phone to a protest, there are two ways it can be used to get information on you, according to Jathan Sadowski, a senior research fellow for Monash University’s emerging technologies research lab.

There’s the passive collection of data, which is information your phone sends out as part of its normal use. Many apps will collect data, such as your location, that it doesn’t need for its normal service to sell as part of its business model, Sadowski said. Just last year Roy Morgan released mobile phone location data that showed where the freedom protesters had come from before the rally.

Much of the data is collected by big tech and telecommunication companies which have enormous amounts of information on large swathes of the population. In Australia, telcos are obliged to keep two years of metadata, which can be accessed by an increasing number of government agencies. Even encrypted messages can potentially be accessed by authorities via Australia’s anti-encryption legislation or accounts taken over under the still relatively new Surveillance Legislation Amendment (Identify and Disrupt) Act 2021.

“Every time you ping off a cell tower, that’s a data point about your location, and you can triangulate that to a pretty precise location,” Sadowski said. “There’s definitely a way for law enforcement to get access to that data by requesting it or subpoenaing a telco or app or platform.”

Then there’s active smartphone surveillance, which is when devices are used to actively pick up mobile phone signals that can be used to trace or identify people. These range from Westfield’s past use of signal detection to track shoppers, to IMSI catchers, which are devices marketed to Australian law enforcement groups that imitate cellular towers to track devices, block their usage or intercept their communications.

And there is some evidence this technology is being used against protesters. In the US, the FBI and military — who’ve used IMSI catchers in the past — flew surveillance planes over protesters during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests.

The easiest way to stop this surveillance is to leave your phone at home. But as many people need their phones, other options include using a Faraday bag (a pouch that blocks radio signals), leaving it switched off or on airplane mode, or ensuring that Bluetooth and wireless functions are disabled.

Facial recognition v privacy

Another way of tracking protesters is using their faces. Facial recognition technology that allows the rapid identification of someone from an image or video is an emerging form of mass surveillance and tracking.

There are multiple facial recognition products that allow users to scan faces against enormous databases of stored faces to find matches. Some like PimEyes are available to consumers, whereas others, such as Clearview AI, have been trialled by police.

Digital Rights Watch chair Lizzie O’Shea said the use of facial recognition technology threatens the privacy of protesters.

“Facial recognition technology has the potential to identify any person attending a protest,” she said.

Because there is very rarely any recourse to unwanted surveillance if you are in public, O’Shea advised using a mask or other methods to obscure your face.

“You should be wearing a face mask anyway to prevent spread of COVID-19, but also consider face paint or creative use of make-up to help protect yourself from facial recognition technology,” she said.

She also recommended wearing plain clothing and covering tattoos.

Avoid digital footprints

There are a number of other ways that you leave digital traces that you might leave when choosing to attend a protest, said Deakin University senior lecturer in criminology Dr Monique Mann.

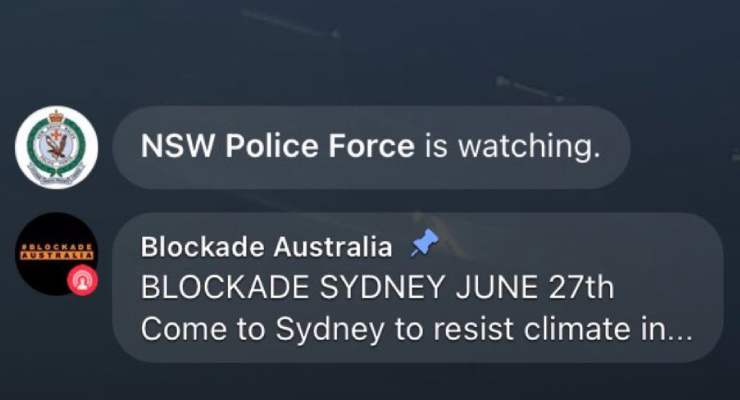

Photos and videos can help identify individuals after the fact. These files often contain metadata that will provide information about when and where it was captured. Also, details captured in the footage may help track down other protesters. NSW Police was observed watching a Blockade Australia Facebook livestream earlier this week.

Mann said to be careful about sharing footage to social media, and to consider stripping data if you choose to and taking steps to conceal the identity of anyone captured in the footage unless they’ve also consented. Mann also suggested using encrypted messaging services such as Signal to contact others if you must.

“While I know Australia has undermined encrypted forms of messaging, you might as well make it harder,” she said.

How you get to and from a protest is also subject to tracking. Automatic number plate recognition technology can be used to monitor vehicles, and has been used by police to track people’s movements during NSW’s lockdown measures. Similarly, using a transport card such as a Myki or Opal card leaves a digital footprint.

“When I was at Hong Kong’s protests in 2019, I watched people line up to buy paper tickets and not use their normal cards to avoid surveillance,” Mann said.

Some groups such as activists, civil society organisations and people of colour have traditionally been at a greater risk of surveillance and may want to be more cautious, she said, but it served everyone to be mindful of their privacy while protesting.

Yes and we also need to know what happens to people when they are indentified and tracked.

Does the tax dept suddenly take an interest and audit you? Do the police pull you over more often and spend time checking your car so they can defect it? Does Centrelink audit you even tho they never have before? What can these creeps do to punish people who take part in protests?

There may be many ways people find their lives become more difficult after participating in a public protest.

Once upon a time, the state protected us from terrorists.

Now the state IS the terrorist.

Is it really? An illegal protest that disrupts city services is something I would like the police to deal with.

It’s not hard to peacefully protest. Teachers and nurses do it all the time. They aren’t being surveillance by the state.

The right to whinge does not supercede the rights of non-whingers to go about their lawful business unimpeded.

Defining the means of protest illegal can be a way to simply limit protest. As for peaceful protests. Fortunately the suffragettes were happy to chain them selves to Buildings and impede traffic. So we’re anti slavery. Not every social gain you have was won by following someone else’s playbook.

As George Monbiot pointed out last week –

https://www.monbiot.com/2022/07/04/fight-to-survive-another-day/

It’s a rare occurrence, one might suggest accidental, when the law is not the crime, considering for and by whom most legislation is written.

That appalling bloc the EU has robust surveillance protections under the GDPR:

‘Any form of surveillance is an intrusion on the fundamental rights to the protection of personal data and to the right to privacy. It must be provided for by law and be necessary and proportionate.’

One doubts that civil protests and participants could be legally surveilled but in Australia, like the US and other authoritarian nations security organisations seem free to do what they want…. even if against freedom of speech, assembly etc.

“Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.”

Does Bunnings send to police facial recognition data of people who buy wooden stakes on the mornings of protests?