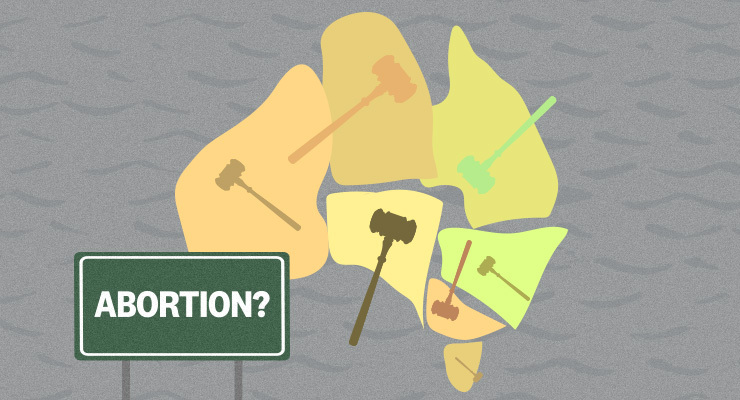

South Australia yesterday became the latest state to enact laws decriminalising abortion. For almost a decade, more than three-quarters of Australians have agreed that abortion should be legal and accessible. And it is, apart from in Western Australia. But there is still no nationally uniform legislation.

Between states, requirements differ for women accessing abortions, doctors referring or providing them, and support personnel, as do permissible timeframes for termination and the number of doctors required to sign off on it. Within states, it’s a postcode lottery.

One of the biggest differences between states and territories is gestational limits on abortion, after which a doctor (often plural) needs to stamp their approval. In the ACT and Tasmania, abortions are only legal up to 16 weeks of gestation, while in NSW and Queensland it’s up to 22 weeks. The Northern Territory allows abortion later than any other state at 24 weeks, while South Australia allows it up until 22 weeks and six days.

While WA hasn’t yet decriminalised abortion — meaning it’s still dealt with in a legal framework instead of health legislation — abortions can be performed up to 20 weeks provided it has been approved by two doctors. A panel of six doctors has to approve the service after 20 weeks.

Doctors can conscientiously object to providing abortion services, and just a fraction of them are registered to provide medical abortions. New data provided to Crikey by Marie Stopes International Australia — set to be released next week — shows as of this month there were just 3441 medical professionals certified to prescribe the abortion drug Mifepristone.

So why is the system so complex and convoluted? If there is a national consensus, why not implement uniform legislation across the country?

A melange of legal measures exists because there is no constitutional right to abortion in Australia. Whilst the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) does offer the odd regulatory standard on pregnancy termination, it is up to the states and territories to lay down the law.

Dr Tania Penovic, research lead in gender and sexuality for the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law, agrees that Australia does have a “patchwork framework” that would benefit from being streamlined, but stresses that state- and territory-led laws better serve the interests of women.

“The greater uniformity there is between states and territories, the more workable and accessible abortion will be,” said Dr Penovic. “However, to get uniformity by federalising the system may do more harm than good.”

And then consider politics and power plays. State legislation is better insulated from a science-vs-ideology showdown. “When you see how easily rights can be taken away and how easily religious influence can be brought to bear, look at the Morrison government’s religious agenda, I just don’t think it’s feasible,” said Dr Penovic. “It is concerning the disproportionate effect religious actors and people have over medical professionals.”

The state- and territory-based approach to abortion legislation does better protect abortion rights, but women and doctors alike would certainly benefit from less hodgepodge and fewer hurdles.

“A melange of legal measures exists because there is no constitutional right to abortion in Australia.”

Actually, that’s not the case at all. The substantive reason is because the Commonwealth has no power under section 51 to regulate abortion, indeed any specific medical matter. And just as with just about every other area where the Commonwealth does not have express power, ‘national’ regulation is a hodge-podge of varying State (and sometimes Territory) regulation.

Agree entirely. What were the drafters if our constitution thinking!!

You keep saying this but WA was the first to decriminalise it. Where do you get your opinions:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abortion_in_Australia

Oh I looked at your profile and let me tell you a little story.

Many years ago a little boy went to school and told the class about his brother in the freezer….this was not an urban myth it is what happened in Western Australia and led them down the path of decriminalising and making abortion legal.

The reason that you are spreading misinformation which can harm woman is probably because

and

3 you are an Eastern Stater which likes to think it is superior and more advanced in being a decent human being then people in WA.

That NSW only decriminalised abortion last year is just a reflection on how woman’s health is treated in NSW with the most likely to suffer being regional woman.

The bill of rights within the constitution of the united states of australia DOESN’T contain a right to abortion??!!

What were our founding fathers (Ned Kelly and Banjo Patterson) thinking??!!

Our president should fix this straight away.

First question

Is our system working, if so leave it be else you will have a system that doesn’t work like

Medi Care

Education

Aged Care

Why do we have to take the lead from america when they get is so wrong often.

Another story for the sake of a story, why do we have to import american problems

Alabanese need to be very careful ruling on every “progressive thing that turns up in the new. Leave that for the ABC( New Idea) to report on.. This is what occurs in China and Russia where the person at the to rules by whim.

Ask Kevin Rudd why he was punted, ask Scott Morrison, they got involved in the day to day running of the country.

Yes he did not have to come home to ‘fix” the fires it was not his job. That what others are paid to do and he would have made a mess of it anyway. So be careful what you wish a PM to else he may become Supreme Leader, is that what in australia

left a few words out for the nitpickers to have a go at. There message is there tho