Talk about an October surprise. Sixty years ago this week, as the 1962 midterm elections approached, an American U2 spy plane captured photos that confirmed the Soviet Union was installing nuclear missiles in Cuba. So began a tense international showdown known as the Cuban missile crisis.

For 59 days the world teetered on the brink of annihilation as the two superpowers faced off. It was the closest we have come to nuclear war since the advent of the atomic age.

Last week US President Joe Biden invoked this memory when he warned the risk of nuclear war is greater now than at any time since the Cuban confrontation. He was speaking in response to thinly veiled threats by Russian President Vladimir Putin that he would “without doubt use all available means to protect Russia and our people — this is not a bluff”. Biden worried that detonation of a tactical nuclear weapon by Russia might easily spiral into “armageddon”.

After the Cuban crisis, the US and Soviet Union embarked upon a series of de-escalation and disarmament initiatives to prevent future disputes from spinning out of control. The first was the installation of the hotline between Washington DC and Moscow — a teleprinter at either end, not a red phone — that allowed direct communication between the two countries’ leaders.

In 1968 the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) was introduced, committing nuclear-armed states to dismantle their stockpiles and other signatories to forsake adopting nuclear munitions. The following year the first bilateral arms reduction talks began leading to the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. These were followed by more comprehensive pacts between the US and the Soviets that resulted in the decommissioning of tens of thousands of warheads, missiles and bombers.

The end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union meant a potential nuclear nightmare receded from public consciousness, supplanted instead by fears of terrorist attacks. However, the genie was never put back in the bottle. The original nuclear powers have not fulfilled their NPT commitments to retire their nukes, and several more nations have since joined the atomic club. Only South Africa and, ironically, Ukraine have eliminated their nuclear arsenals.

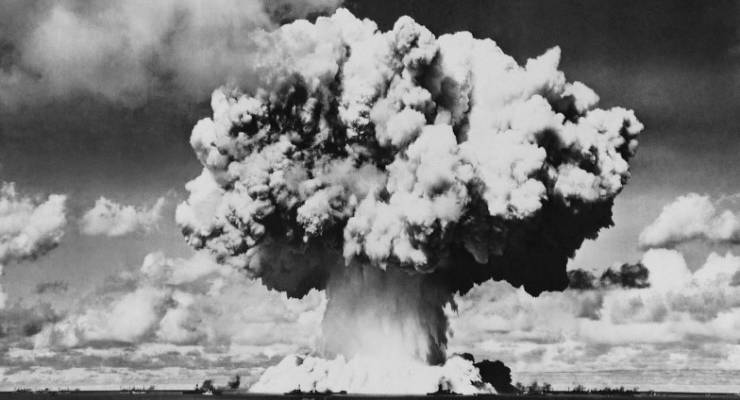

It’s this complacency that Biden was addressing with his remarks. After living for decades under the shadow of the mushroom cloud, we have become inured to the ever-present danger that nuclear weapons pose.

Putin’s resort to nuclear blackmail is a rash attempt to stem the battlefield corrosion of Russia’s military and forestall a humiliating defeat. This does not mean a nuclear strike is imminent, or even likely. Exploding a tactical nuclear device would not alter the strategic calculus for Ukraine or the West. Ukraine is locked in an existential war. Its people have no option but to fight. A nuclear explosion would redouble its allies’ commitment to that cause.

Diplomatic efforts would further isolate Russia from the global economy, placing more pressure on the regime to end its invasion. Joseph Cirincione, nuclear security expert and former president of the Ploughshares Fund, outlined additional measures that could be imposed, including expulsion from the international banking system, a worldwide ban on all Russian energy exports, a cyber shutdown of Russia’s electrical grid that would turn Moscow dark, and the prospect of legal repercussions for senior officials responsible for implementing Putin’s order.

Moreover, the West might retaliate with a massive NATO-led conventional counterstrike to cripple Russia’s forces on Ukrainian territory. The domino effects such a response would elicit are uncertain at best.

The mere suggestion of Putin using a tactical nuclear weapon is intended to erode the taboo against first use and normalise the notion of “limited” application on the battlefield. There is nothing limited about a tactical nuclear weapon. Depending on its explosive power, even a small warhead could rival the “Little Boy” bomb that flattened Hiroshima and vaporised 100,000 people in an instant. John Hersey’s classic Hiroshima is a timeless record of the true horror that blast unleashed.

Despite his sabre-rattling, Putin remains savvy enough to understand the risks should he cross the nuclear Rubicon. This is another reason for Biden’s public comments. Along with back-channel diplomacy detailing the consequences such a choice would bring to Putin’s doorstep, they are intended to deter him from pressing the button.

Notwithstanding that it would be a catastrophic mistake, we can’t exclude the possibility that Putin may do it anyway. It wouldn’t be his first flub. He blundered into the Ukraine invasion with foolhardy swagger, only to discover that his military’s vaunted prowess was as illusory as Potemkin’s villages. That disaster has boomeranged to doom his vision of a reconstituted Greater Russia, and threaten his grip on power at home.

Desperate men are prone to desperate measures. Having backed himself into a corner, Putin has no good options to recover his footing. He has told us he isn’t bluffing. Prudence dictates that we should take him at his word, and prepare for the worst.

Do you think Putin is crazy enough to press the nuclear button? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Another ridiculous article from Crikey. Putin has never said he would permit first strike use of nuclear weapons. He has simply stated what we all know. NATO would use nuclear weapons against an attacker. The US would use them too and has now dropped it’s no first strike policy as well. Russia will too as will China, India and all the other holders of these dreadful weapons. As to rational leadership, when I listen to Lavrov and Putin they seem like adults. Admittedly they coldly assess the forces against them but when I hear Boris, Liz Truss, Biden and Schultz declaim, they seem full of hot air and dangerous hyperbole. If you don’t believe me check out Professor Jeffrey Sachs, Alfred de Sayas ( UN special procurator and a US citizen), Noam Chomsky, Jacques Baud former head of Swiss intelligence Scott Ritter UN weapons inspector for the real story on how we got into this mess. We are in a dangerous place and the US is primarily at fault. There is plenty of blame to go around but NATO bears the brunt. Ban all nukes!

Nonsense. Russia’s military doctrine allows first strike use, this is not a secret. Russia says it will use a first strike only as a defensive measure in critical situations. Whatever that is, it would still be a first strike.

Sorry SRS not exactly correct. Allowed in circumstances of an existential threat. Then research the history of Ukraine. US advisors and politicians (numerous) have stated since the 90s if Ukraine was taken by the west it would be perceived as an existential threat by Russia. This is common knowledge to the USA.

So yes the Russians regard this as a potential existential threat and the US knows this as they are the one that set up this proxy war – the third one between Russia and USA. Yes Aussies were involved in small numbers in the first attempt over 100 years ago.

There is a lot of history in this one. I have not mentioned Poland and Germany. Start with Stepen Carey’s references as an introduction.

Sadly I am at odds with a lot of contributors in these pages as I am anti war. A concept that some find apparently threatening because I do not agree with their narative. I seek only the truth and peace.

If you’re anti-war then you must be really against Putin as Russia rains down missile after missile on playgrounds, hospitals and other civilian targets in Ukraine.

Ukraine has been shelling exactly the same targets in the Donbas region for the LAST EIGHT YEARS – but they were Russian speaking separatists so I guess thats all ok…

Secretary General of NATO Stoltenberg “…As you know, NATO Allies provide unprecedented levels of military support to Ukraine. Actually NATO Allies and NATO have been there since 2014 – trained, equipped and supported the Ukrainian Armed Forces.”

https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_197902.htm

Sophist pedantry – “first strike” is the widely accepted term for ICBM attack as in the well named MAD policy which the Hegemon will not promise, even as a non-core, to eschew.

Defensive or battlefield use is an entirely different kettle of turds, and was an integral part of the septics’ Fulda Gap fantasy plan.

Or when Thatcher sent their nuclear armed sub, HMS Conqueror, to Falklands though it ‘only’ used conventional torpedos to sink the Belgrano.

The not-so-subtle sotto-voce threat was to Buenos Aires if things went awry.

I especially like your “different kettle of turds”. I’ve already up-ticked your post.

First, let’s avoid credible sources whether Russian &/or Ukrainian?

‘NATO would use nuclear weapons against an attacker’ this has not occurred but Peter Jukes of ByLine Times (font of info with ppl on ground), who had worked for RT in UK, said that apparently warning had been made months ago to Russia, through security channels, that any tactical nuclear use on Ukraine would result in US conventional strikes on military/security infrastructure.

While faux Anglo analysts & protectors of Putin inc. Sachs, Mearsheimer et al avoid using any current and credible sources from the region Hungarian media (Portfolio.hu) have reported this:

‘Nine presidents condemn Russian missile attacks in Ukraine as a war crime. The Presidents of Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania and Slovakia…’

However, Anglosphere Putin apologists of right and left demand that we ignore the nations and citizens affected most?

Who would be a food taster for Vlad right now?

Any replacement would be worst and more organised and competent

The Cuba crisis

Doubtful. The 1983 NATO exercises code named ‘Able Archer 83’ came much closer to triggering full nuclear war, but somehow this is usually ignored.

Even closer was the time migrating geese looked like Russian bombers on the radar. It seemed to give the US 30 minutes to launch theirs.

There may not even have to be a strike if something is not done to restore electricity to the large nuclear power plant in Ukraine, which is used to cool the reactors. It will blow up and apparently create havoc across Europe as well as Ukraine and elsewhere. That is scary.

But the Russian elite *hates* Ukraine. They envy it so much because their greed stops Russia from having the same great potential as Ukraine.

From Alexei Navalny – “First, jealousy of Ukraine and its possible successes is an innate feature of post-Soviet power in Russia; it was also characteristic of the first Russian president, Boris Yeltsin. But since the beginning of Putin’s rule, and especially after the Orange Revolution that began in 2004, hatred of Ukraine’s European choice, and the desire to turn it into a failed state, have become a lasting obsession not only for Putin but also for all politicians of his generation.”

A couple years ago a TV doco aired in which a former KGB colleague of Putin’s was being interviewed. He described Putin as ‘a snake’, chillingly adding that when a snake is backed into a corner it always strikes.

Putin is a “proceduralist”. Really, a rather grey man, a nationalist, sticks to the rules, sticks to procedure, not charismatic, highly intelligent, plans for the long haul and generally doesn’t speak without thinking it right through and believing he will deliver. If you think he is backed into a corner at the moment, you’re delusional, like most of the west.

“highly intelligent” – said on day two hundred and twenty something of Putin’s 3 day war while Norway and Finland apply for NATO membership and China goes quiet on its Taiwan threats and even publicly expresses support for Ukraine.

I’d hate to see how badly things would go for Russia if Putin wasn’t so bright.

Agree, while people focus on Putin what would be the reaction of Xi or China, plus India etc. if he tried to use nuclear weapons? Little if any support except North Korea?