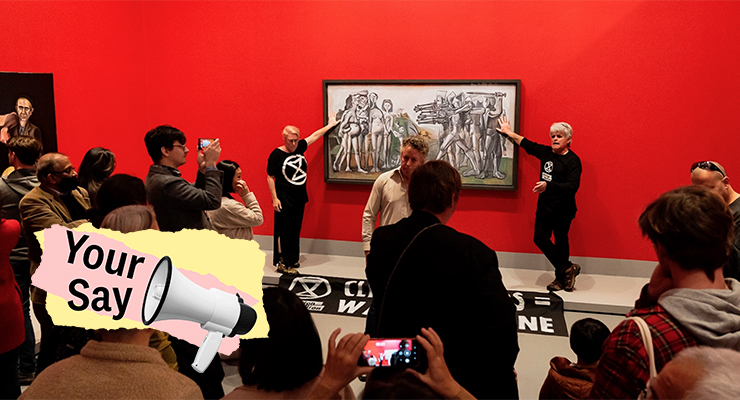

In Your Say, readers tell Crikey what they think about our stories. Today Picasso’s attitude to art gets a guernsey, as do “archaic” rape trials, and church v state.

On why Picasso would have approved of Extinction Rebellion

Dr Martin Wolterding writes: When one smells the smoke and distant crackle of an approaching wildfire, how do we wake up our neighbours to the danger? How do we pull them from their media-induced dreams of pleasant safety to the reality that their lives, and that of those they love, are in peril? How do we overcome their completely natural reluctance to leave behind the illusion of safety and comfort to focus their attention on a real and present hazard? If a yell doesn’t penetrate their sleep, a slap might — though in the instant they will hate us for it. This is our dilemma. To warn, to wake up our community to the looming crisis.

Alex Mungall writes: Let me see why the XR protest was justified. We are:

- World (OECD) leaders in coal as a percentage of our electricity generation

- World leaders (with the US and UK) in flight emissions per head of population

- SUVs now make up 50% of our auto purchases

- World leaders in extinctions of our animal species.

Do Australians believe humans are responsible for climate change? Do we believe our impact matters? Or is climate change caused by other humans? We need to hear, see and feel the result of our actions and causes and understand them better.

Stephen Glasby writes: I am sure the media and the public would love it if XR protesters superglued their hands to a political billboard, or the car of a politician or a fossil fuel CEO. I recall BUGA-UP was effective against unhealthy billboard promotions (tobacco, junk food, etc) and had broad public support. Nothing much changes unless the rich and powerful are inconvenienced or embarrassed. While I am sure that XR seeks to minimise inconvenience for the public, embarrassing or inconveniencing powerful “problem people” is a noble goal.

Ross Brown writes: I applaud the actions of Extinction Rebellion getting the climate issue out into the news cycle as much as possible. To critics I say: instead of being ashamed and apologetic about being too white and middle class (and doing nothing as it appears they want us to do) I and my ER friends are using our white privilege to try to do some good in this troubled world. We’re trying to let our brothers and sisters in nations suffering from the climate crisis know that we hear them. As people with white privilege, we can afford to be a bit braver and risk going to jail to get this important message out. The police are less likely to kill or hurt us.

Frances Quin writes: I thought it great that XR activists glued themselves to the Picasso painting. I look forward to seeing more of this sort of activism from these gutsy people, and how good is it that both activists were older people, part of the generation that is rightly blamed for the mess of the world now. I am 64 and acknowledge my part in all this chaos.

On ‘archaic and shameless’ rape trials

Amanda Brady writes: I totally agree that there should be a delay in reporting names of people involved in rape and other sexual assault trials. With social media providing invisibility, reducing empathy and normalising hate, it is imperative our laws provide people with some protection. If they are found guilty then names could be reported, but I still think the victim should be allowed privacy if desired.

Karen Rowland writes: I absolutely agree with delaying naming defendants in rape trials. Their names and reputation are immediately affected and sullied for months while waiting for trial. It seems like guilty until proven innocent being played out all over news and social media instead of how it should be: innocent until proven guilty. I also agree the victim shouldn’t be named until after trial — especially if it might stop them from coming forward in the first place.

William Grosvenor writes: I agree that changes need to be made but it seems it’s almost too difficult a problem. I’d like to suggest that the female signs a certified statement which some legal person could consider and decide if it should be sent for trial. If it is, the female’s statement is a given without any cross-examination and it’s up to the male to prove he had consent or it didn’t happen, which is subject to cross-examination. That should level things up a bit.

Kathy Crawford writes: Madonna King implies that if an alleged sexual assaulter is found innocent he should never be named. Which assumes the verdict will be correct. The vilification of victims, even with a guilty verdict, is far more of a problem. In good conscience I could not encourage any of my daughters to pursue justice in the event of a sexual assault where there are no witnesses or clear corroborative evidence.

Anne Schmitt writes: I agree these types of court cases should be kept out of the public sphere totally. I have been horrified by what Brittany Higgins is going through. And the word-by-word reporting of every nuance is demeaning, for her and her accused. This should be a closed court case, no names, no commentary until a verdict is reached. How can the jurors have a balanced, unbiased view of the case when it is all over the news? I can understand victims being hesitant to report or press charges. This is horrific.

Chris James writes: I agree that reporting of rape trials should be delayed until well after a court trial and decision. In a social media world — where a person’s name and life details (both the accuser and the accused) can be disseminated globally within hours — the dynamics of the media’s need to know has changed. The damage done to accused people who may turn out to be innocent can be vastly disproportionate today. Just the mention of a name in a rape context may destroy an innocent person’s life forever. We do not need to know the name of accused people at all, ever, only the names of guilty people.

On the need to truly separate church and state

Karin Diamond writes: I found Michael Bradley’s piece on the legalities of the Andrew Thorburn situation and government financial support for religious organisations infuriating. I’ve been banging on for years about my taxpayer money going to them. The problem of course is how any government will ever make the move to pull back our hard-earned money from these religious organisations. This is nothing more than political expediency pandering to the religious vote — shameful behaviour really when, as Bradley pointed out — at least 60% of us (as of today) have moved on.

I can’t imagine that this issue is even on the radar of Labor or the Liberals or the Nationals. Side players like Greens, teals and Reason are somewhat engaged, but how do we get leverage? Could we use the argument that the money could be better used on schools, hospitals, aged care, NDIS, sporting grants and car parks?

Bob Pearce writes: I believe that churches should have the same tax status as ordinary Australians in that they should be allowed to claim a tax deduction for their charitable works and those works should be clearly defined. The tax laws should be applied to churches as they are applied to all other businesses.

Humphrey Bower writes: Michael Bradley’s article on discrimination law and state funding for religious organisations dissects the issue in a way that perpetuates discrimination by all parties: church, state, organisations and individuals. Anti-discrimination law should be applied to discrimination on the grounds of identity or affiliation (religious, cultural, racial, sexual, gender, disability, etc) rather in terms of belief (which Bradley rightly observes is subjective).

People should be free to think as they wish, or be who they are, without being discriminated against in terms of employment, funding or hate speech, and (crucially) without practising such forms of discrimination themselves. No organisation or individual should be legally sanctioned or hired or fired on the basis of who they are or what they believe, but solely on the basis of what they do.

On that basis, it is equally true that Andrew Thorburn should not have been pressured to resign because of his religious identity or affiliation; that pastors in the church he attends should not have made homophobic public statements; and that the state should not withdraw funding from religious organisations unless those organisations breach anti-discrimination law in terms of their actions or pronouncements. All these are equally acts of discrimination, and there is no conflict between them.

If something in Crikey has pleased, annoyed or inspired you, let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

So called religious organisations shouldnt lose their tax free status because they are discriminatry. They should lose them because they should never have had them in the first place. Industrial religions as I call them are not there to do anything good. They are there to groom entire populations to blindly accept being exploited by the status quo, including the government. Along the way they feel entitled to do a bit of exploitation themselves and they do as we have seen.

Take away their tax free status and never give them any grants ever again. And no more free passes in the courts when they get caught out raping the kids.