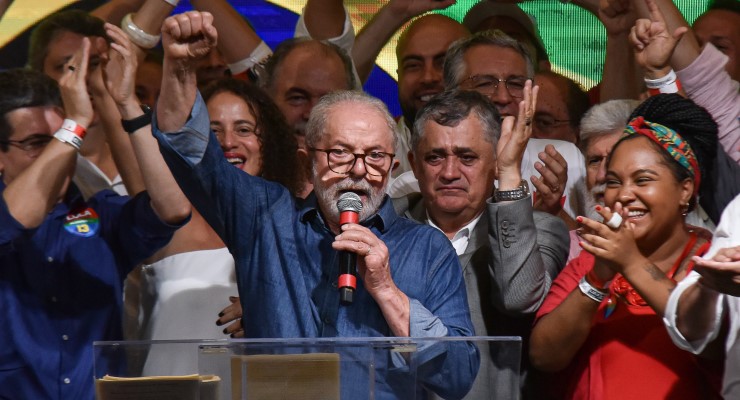

The defeat of Jair Bolsonaro by Brazil’s former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva removes another corrupt, autocratic populist from power.

But as in the US, the circumstances suggest it could be merely a caesura for the extreme right in a country much of which remains controlled by Bolsonaro allies and supporters.

Lula’s margin in the presidential election was worryingly thin — 50.9% to 49.1% — in an economy with persistently high unemployment, high (albeit now declining) inflation, and staggering wealth inequality.

Much of the south of Brazil voted heavily for Bolsonaro, and a key Bolsanaro supporter, Tarcísio de Freitas, won the governorship of Sao Paulo comfortably — in fact, Bolsonaro supporters won more than half the state governorships. Worst of all, Bolsonaro’s party will be the biggest in the new Congress, meaning Lula will be unable to pass legislation without at least some backing from the right.

That result suggests Lula’s charisma, experience and political skills — and revulsion among many conservatives for Bolsonaro — were crucial to ousting the right-winger whose support remains widespread.

It also raises the same questions as the 2020 US presidential election: how can so many people still vote for a figure demonstrably unfit for leadership, a corrupt denialist whose failures led to, in the case of Brazil, 700,000 deaths from COVID? And how can such a figure retain such strong support within his own party?

Bolsonaro has repeatedly indicated, like Donald Trump, that an election result that does not mean his reelection will be a fraud, and has remained silent since his loss, although there are media reports that key supporters are not disputing the outcome.

That may reflect what has become clear from the fortunes of the Republican Party and Trump in the US — that his party will continue to wield power and he stands a good chance of returning to the presidency in 2026.

Bolsonaro might learn from the example of Trump and realise that his chances of returning to power will be increased by not engaging in the kind of treasonous undermining of democracy that has characterised Trump and his supporters since November 2020.

In the meantime, Bolsonaro’s party can block reform efforts by Lula’s administration while blaming the new president if the Brazilian economy fails to recover the once impressive rates of growth achieved under Lula previously.

As with Trump, it would be comforting to believe Bolsonaro is finished, but these profoundly unequal, profoundly divided polities are likely to remain a playground for populists for a long time to come.

“How can so many people still vote for a figure so demonstrably unfit for leadership?” That’s what needs exploring. We know it’s happening with Bolsonaro and Trump, among others, we know there’s a huge amount of anger and mistrust among the voters, we know there’s a lot of misinformation for the gullible to digest like junk food. But there are too many people on the conservative side who aren’t stupid or damaged, who weren’t always morally bankrupt, and who are crucial to the survival of the populists. What are they getting out of it? How and why are they maintaining this farce?

It is always a mistake to blame the voters.

Not voting for “the left”.

You may scoff, but IMHO it really is that simple.

Modern Conservatism is pretty much entirely defined by “not the left”. Even amongst the people you refer to, It has no objective, no vision, no rationale.

Yep, modern ‘conservatism’ is nothing more than reactionary opposition to progressivism.

As many have noted, ‘conservative’ has become a very ill-fitting descriptor for a mob who’ve apparently decided they want to tear up civil society in favour of brutal patriarchal austerity on a poisoned planet.

But then again, conservatism has always been ethically and intellectually threadbare, if not entirely bankrupt. Because of course it’s just a fig leaf, a rationale for submitting to those who dominate.

You have the dominating/submitting the wrong way round – conservatism is about keeping what the dominant group has and the rest submitting to their taking even more.

“What’s mine’s mine, what’s, momentarily, yours is up for grabs!”.

The point is that rulers group can always hire enough thugs to do their bidding in exchange for a, minute, share of what they take from the rest of us.

Our species is less H.Sapiens than H. Obediens or, more accurately, H. Creduliens because so many believe blatant nonsense.

In most species one individual can dominant another and, in the more social ones, dominate a group – of males.

NB not, as so often trotted out by the malignantly inclined, the harem of females who barely notice and certainly don’t obey else the buck/stag/ram/etc wouldn’t spend all Summer trying to fend of rivals, neglect to eat to bulk up for Winter and DIE, making way for rinse, repeat & rut.

We are unique in that Alpha can induce Beta to do something to Others.

“Raid and steal from them, bring the booty back to me and I’ll give you a fraction of it”.

“YES, Saarrh!”

Brazil has a difficult future with the revolting Bolsonaro lurking, an indelible stain. Who voted for this nematodal nightmare?

Who voted for Bolsonaro for president? 49% of Brazil’s voters. The real problem is the federal congress which is the division that is really going to determine Brazil’s future.

My bro has lived in Brazil this past 40 years, we speak most weeks. He reckons the corrupt excesses of the Lula / Rouseff years left a huge middle desperate for change. Bolsonaro was so buttock-clenchingly useless that he alienated just enough of them, but the far right idea has nevertheless taken root quite robustly- as BK points out. Too often a sclerotic, complacent left fattens supporters and alienates marginals with inevitable results. The good news is that the right is no stranger to sclerosis or complacency either.

During his last administration Lula seemed to take the position that anti corruption is not a socialist cause. He was wrong. He was wrong. The fight against corruption is a central socialist cause.

But, of course, corruption is not specific to the PT.

He was wrong, alright. What a piss-ant position to adopt. Capitalism *is* corruption. Proper socialists should be all but prescribing the guillotine for corruption.

Lula adopted the “traditional ” position regarding corruption. That was the problem.

Good article.

However – ‘the circumstances suggest it could be merely a caesura for the extreme right’. Is this a new Crikey feature – the obscure word of the week to puzzle over. So I looked it up.

What does caesura mean in English?

caesura • \sih-ZYUR-uh\ • noun. 1 : a break in the flow of sound usually in the middle of a line of verse 2 : break, interruption 3 : a pause marking a rhythmic point of division in a melody.

I kind of see the relationship being made but question how many people understood the word. It might have been clearer with something like ‘a break in the flow of support to the extreme right’.

Personally I dislike obscure Latinisms – please stick to clear rather than clever communication.

Point taken but BK who has a clear and succinct writing style can, I think, be forgiven for using the occasional interesting, obscure but nonetheless contextually relevant word. The reader only stands to benefit from expanding his or her vocabulary in any event. Thanks all the same for providing us all with the dictionary meaning.

Agree up to a point, but Latinisms dropped into English language writing is one of those annoying British class indicators. If you have worked with the type, you might understand how annoying these and Shakespearian quotes/allusions can be.