Labor and the union movement spend a lot of time congratulating themselves about superannuation (or “super”). Made compulsory and “universal” by accord-era Labor prime minister Paul Keating, Labor frequently mentions super alongside Medicare as one of its two greatest achievements.

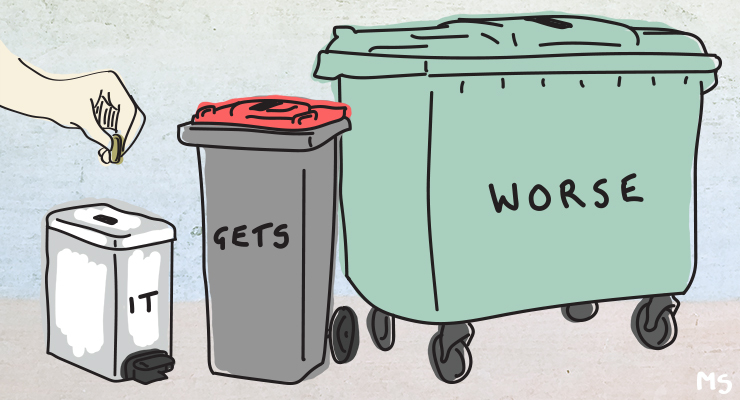

But for those who oppose inequality, poverty and privatisation, or simply like well-designed retirement systems, the truth is that super isn’t an achievement. It’s a disgrace.

Don’t confuse this as an endorsement of super’s opponents on the right. Liberals like Andrew Bragg and Tim Wilson hate super because it imposes obligations on employers — but that’s the good part. The bad part is what happens to the money once it enters the system: contributions go into individual accounts. That fundamental design makes any progressive outcome inherently impossible.

A grim reality

A system ostensibly designed for “dignity in retirement” should help those worst off the most — instead, our income-linked individualistic design replicates and amplifies the inequality and poverty that the poorest retirees experience throughout working life.

Individual accounts mean no mechanism to redistribute. Any group that routinely experiences lower wages or time out of the paid workforce (women, Indigenous peoples, caregivers, those dealing with sickness or disability) has that disadvantage systematically and deliberately replicated in retirement thanks to super’s fundamentally broken design.

Elderly single women are in widespread poverty and financial stress, with many living in cars and tents around Australia — their lack of super punishing them further for the pay sexism and time out of the workforce they experienced in working life.

For Indigenous peoples, there is a further dimension of injustice: lower life expectancy on average means an increased unlikelihood of living long enough to spend savings. Per the Retirement Income Review: “Many of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants in recent survey research viewed superannuation more as an inheritance, rather than a source of retirement income, as they had low expectations that they will live long enough to use it.”

The real story

Inequality in super balances is pervasively underreported and hides the extent of the problem by excluding those with zero balances or no account at all.

Even nominally inequality-focused think tanks get this wrong. For instance, a recent Per Capita report on women’s homelessness claims a median balance of $147,000 for women aged 60 to 65. But excluded from this figure are the 20% of women in this age group who have zero super. When these are included, the real figure is just $86,000 (and only $136,000 for men), according to the latest ABS data.

Remember, this is a median, meaning half have even less. Meanwhile, the super industry describes the minimum standard for a “comfortable retirement” as $545,000 for a single person. Of course, as retirees age, their savings dwindle further. The median over-65 person in Australia has no super at all.

But even if all inequality magically vanished overnight, super would still be a badly designed system. Even relatively well-off retirees worry about depleting their savings. This forces people to overwork to build up a huge hoard of savings, likely to be more than they need, and then underspend in retirement in case they live longer than expected.

A good retirement system should pool money in order to pool risk, giving you a stable income no matter how long you live. Again, super’s individual design precludes this.

Accordingly, the recent Retirement Income Review found typical retirees were overwhelmingly failing to spend their savings, and dying with savings mostly intact. That money then gets inherited, increasing multi-generational inequality even further.

It gets worse. Super interacts poorly with the age pension asset test. Additional (non-home) savings between a certain range ($280k-$620k for single retirees) result in near-zero additional retirement income, as additional income from those savings is almost entirely offset by a lower pension payment.

It’s important to remember that super isn’t magical free money. Each dollar saved is a dollar not spent. That means that super lowers the standard of living of all workers throughout their working lives, including during times of peak financial stress, such as when children are young. This reduction in income can even push them below the poverty line — often for no benefit later.

The bad design of the asset test (particularly the fact that the primary residence is excluded from the test) also creates an entire sub-industry of financial planning to help well-off people game the asset test by doing things like upsizing to unnecessarily large homes.

A costly system

It would be much simpler and fairer to just pay everybody the pension and raise taxes on the wealthy to make up for it. However, this would be too much of an embarrassing admission of defeat for those who’ve advocated for super on the grounds that it saves the government on pension costs.

Sadly, even that is a cruel myth. Instead, it costs the government $45 billion in tax breaks (which flow overwhelmingly to the already wealthy), while only saving about $9 billion in age pension costs.

Super costs the economy a further $30-$35 billion each year in fees — about twice what Australian households spend on electricity. The superannuation “industry” has roughly the same annual budget as the Australian military and employs roughly the same number. Per invested dollar, it’s about 20 times more expensive to run than Norway’s $1 trillion publicly owned pension fund. By comparison, total age pension payments (not administration costs, total payments) are only about $50 billion annually.

There’s more. Superannuation non-payment costs workers $5 billion a year. Wage theft of regular wages is about $1 billion a year, meaning that super is responsible for the vast majority of wage theft, in spite of being only about 10% of the country’s total wage bill.

Beyond the immediate financial effects, super undermines public ownership and enables large-scale privatisation, because all the wealth in super, even in the “good” industry funds, is privately owned and managed. Superfunds own many of the country’s natural monopolies that should be public (toll roads, airports, phone towers), whose returns, once again, flow overwhelmingly to the already wealthy.

Rethinking support

Fortunately, there’s a simple solution: pensions.

Unlike super, pensions reduce poverty and inequality by redistributing downwards. Unlike super, pensions solve hoarding and fear of running out because they’re paid out however long you live, and not inherited. Unlike super, women aren’t punished — pensions are paid the same regardless of gender. Unlike super, pensions aren’t vulnerable to wage theft.

There is upwards of $3 trillion in total super savings, more than $800,000 for every Australian over 65. But super wealth is so concentrated that only the top 3-4% have this much in their accounts.

Redirecting future contributions, or even a fraction of that excess wealth, away from individual balances into a publicly owned pension fund could massively raise and universalise pensions, eliminate retiree poverty, lower inequality, and reverse super’s legacy of privatisation.

Unfortunately, everybody involved in creating and running super is far too busy patting themselves on the back to bother themselves with such trifles.

Has super worked for you? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

What a brilliant article! The current system certainly unfairly benefits the wealthy.

Utterly, absolutely true.

Our great system guarantees that the poorer you were in your “working years”, the poorer you’ll be in old age.

11,000 super accounts exceed $5M. The biggest is $400M.

PJK’s neoliberal dog-eat-dog catastrophe.

Wonderful work, Robert.

Looking at the level of response to this article compared with most others, I am growing more convinced than ever that most people who write comments on Crikey, the mainstream media, and possibly Twitter too, are retired, Who else has this much time on their hands? The tell in this article is the subject – clearly one very close to the self-interests of the subscribing readership.

The point about the amount of time commenters must have on their hands is well made. The second point about the subject matter being of more interest to the retired might also be true, but if so those who are not retired are being insouciant. This topic affects them substantially now, before they retire, as well as later. Ignoring it will not help them. They might not have an interest in the sense of being curious about it, but they certainly have an interest in the sense of a stake in the matter, or self-interest if you prefer, whether they acknowledge it or not.

Agree, but not just for now and current retirees but generational, into the long term future….

If you’re already retired, Superannuation as it exists today is mostly, if not entirely, irrelevant to you. You’ve already benefitted from it (or not), under a very different set of rules.

How does that work, claiming that upon retirement any super income, with or without a part pension to supplement, is useless and not wanted by retirees? Contorted logic or what?

Just… wow.

I plead guilty. But the reason I’m interested in this article is that I started it being appalled about someone dissing Super, and ended up thinking he had a good point.

And what was that ‘good point’ apart from past and present loopholes of benefit to the wealthy under LNP/IPA regimes, that can be tightened up?

Suggests future generations should not have benefits of super, but should pay higher taxes to support more retirees via pensions, or better, crash budgets a la ‘Trussonomics’ i.e. ‘Kochonomics’ for no pensions nor society in future?

Yes – this is an excellent article and draws together many of the issues and problems that have lingered, festered and been ignored for more than 20 years. This includes the negative gearing scandal, ongoing tax rorts, including Super (very high tax-free balances) and general tax evasion/avoidance. The fear of an honest discussion about reviewing all these policies and actually making the changes prevents the action needed and highlighted by the article. The result: worsening inequality and corruption of our society!!

The real issue is; can/will the Albo Labor Govt be prepared to do anything about it ????????????? 2023 is the year that things will have to begin to change!! Quite frankly, The Voice is not the big issue at all- it is becoming another culture war distraction.

We could also be dole bludgers, or cripples and loonies on a DSP. Or the uber-wealthy (from whose anuses the light of God doth shine most brightly) who have no need to work.

Retirees mostly and from what I can glean most are retired, past or present Public Service employees. The latter of course are “working hard”.

It wouldn’t be economically rational to spend time and money on staying informed, and the commenters are reasonably generous, granted from the safety of having benefitted from the great sell off at least financially.

Most Crikey readers want to read about change ,flushing out greed and ideas and have potential to learn in a general media desert. Is my guess.

Anyone with an interest in the Australian economy should have an interest in Super as it plays such a huge part in it.

Amazing how the Norwegians are cited yet again as having created a better system, why can’t brilliant minds in Australia manage the same. I suspect some of the answer is that Australians as a whole object to paying a reasonable level of tax.

Australia’s move to a privatised retirement savings system occurred at a time that blind faith in markets soared. Countries that went against the tide of fashion and stuck with sovereign wealth funds have done very nicely on financial terms and arguably (the case the author makes well) better on social outcomes. A series of choices that glorified free-market solutions over public/co-operative ones – Super, housing, schooling and health – has put us on to a very different trajectory to the ideal our country once held as dear. The trajectory heads toward the wealthy retreating into gated enclaves on beach-fronts and mountains and the great unwashed out on the wasted plains. RIP egalitarian Australia.

And yes, we have become a very tax averse culture. It has been a triumph of short-term appeals (we all want some more in our pockets this year, ergo a tax cut is good) over longer term goal of net life satisfaction. As a society we chose to demonise social welfare and exonerate tax dodging. We’re not alone, as the Panama Papers address files showed, but the divergence from the image we have of ourselves as the land of mateship where we all end the day’s work on the land sharing a coldie….more stark here than elsewhere.

No, spotting future demographic decline while many systems in Europe are not sustainable due to lack of political will, when the above median age vote is increasingly overpopulated by retirees and pensioners…..

Why? Ignore that all Australian citizens are guaranteed a minimum retirement income via the state pension &/or super (latter becoming more significant), what’s the problem apart from more tweaking or regulation?

I’m old enough to remember many thousands of ordinary working people retiring with a few dollars in the bank pre super.look at the US where many millions retire with nothing saved because they are hell bent on surviving, let alone buying a new fridge or telly. Keep the super system but reform it in favour of the battlers. Remember, apart from Medicare, super is what conservatives hate most.

Very sceptical and suspect i.e. astroturfing from who appears to be an IT type, offering opinions and ideology as analysis on a key policy area helping employees, into the future? RW libertarian modus operandi i.e, the ‘libertarian trap’?

No apparent expertise in finance, budgets, pensions or demography, let alone unions & employees’ interests, yet making many unfounded claims round finances etc., but bypassing essential data, over the long term?

Why is this similar to what could come out of the Libs, legacy media & SkyNews, IPA and eugenicists of the social order, in an effort to stymie superannuation under the guise of super being against unions’ and employees’ interests, now and long term?

If this analysis was followed, as many commenters agree, what are the risks ahead for those entering the working age cohort now?

Yes what you say is possible. Crikey should do more than an opinion piece, this topic is far more complex than has been presented.

Classic PR focus on the now and encourage -ve perceptions…..but ignores future demographics.

It’s nothing like anything that would come out of them. This article is diametrically opposed to their views.

Literally nothing anywhere here has anything to do with “eugenics”. Or, indeed, any other time you’ve used the word.

Same thing as always. Conservative Governments.

No, denial of demographic decline to enable dog whistling of immigrants and taking away workers’ benefits…. what’s next card in the deck, promoting the ‘degrowth’ or autarkist economy?

RE: “It needs to be scrapped.” – another “throw the baby out with the bathwater” mentality IMO. That part reads like a somewhat childish hissy fit to me.

Agree with a lot of the points (which are well made IMO), particularly the pension etc. But a more credible argument (IMO) would have been to address issues in both areas. Super only operates as part of the broader tax and investment laws, so realignment is as much about the broader context as super itself.

The LNP have also had a big hand in taking what was a retirement income to a tax dodge. So perhaps that should have been mentioned too.

The inheritance part can be dealt with by tax changes, nothing to do with super by itself (and super has taxable and no taxable components upon death).

Anyway thanks for the article, it is both thought provoking and irritating (to me).

I agree, super was never designed to produce wealth redistribution (that along with inflation control is more properly a task for taxation) so criticising super for failing to do something it was never intended to do is naive at best.

Yes, superannuation was not designed for wealth redistribution, but that’s missing the point. Thanks to its design superannuation is a major contributor to wealth redistribution, by making inequality worse. Whether this wealth redistribution is intended in the design is irrelevant, although it really would be ‘naive at best’ to think it is not intentional that various ministers have chosen over the years to make superannuation such a useful tool for the wealthy to avoid taxes on an enormous scale.

Are we now moving to an Authoritarian State where Individuals are forced to spend their money whether they want to or not?

If the funds were not in Superannuation they would be somewhere else and still distributed to peoples children (which is their right).

So what’s wrong with that? If the pension provides everyone with a good living in their old age, people would still be able to have their private savings which they could use as they saw fit, or leave in their will.

In short, it’s not up to you, me or the Government to decide what someone does financially as long as they do it legally and don’t sponge off the taxpayer.

Only a bunch of guaranteed income, retired, ex-Public Servants would think this is a good idea.

Next will be the call for Death Taxes! A truly horrible tax which thankfully died years ago.

Yeah well the point is the ludicrous Super tax breaks mean the S/super-wealthy currently ARE sponging off the taxpayer. Right? All that deft dodging of their marginal rate, progressive tax system obligations.

Get it? Like housing tax breaks, Super is repulsively weighted to favour high income earners, by minimising their collective tribal contributions at the point of their most privileged. As with all unfair economic systems…it’s not about how much the rich earn. Good luck to them for that. It’s about how much tax they can contrive to avoid stumping up on it.

The Boomer Super Cult was always another case of biddable, stupid Lefty journalists knicker-droppingly seduced by Keating’s Secular-Hillsong/ Fiscal-Hallelujah! Bulldust. As if he invented the magicke concept of…COMPOUND INTEREST! (Hallelujah!) I said COMPOUND INTEREST!!! Brothers and sisters!!

HALLELUJAH!!! We can ALL be rich!!!

Amen!!!

What ludicrous tax breaks? There are caps on contributions and caps on retirement benefits that receive concessional tax treatment. You may find that those with significant super balances contributed funds designed to encourage self-employed people to fund their retirement. Most SE people are not the greatest at retirement planning.

Those same tax breaks are available to everyone. Don’t whinge just because others have worked hard and taken risks that some others haven’t been prepared to. That’s why some are wealthy and others are not.

BTW. Unless you invest in Capital Guaranteed investments only, “Compound Interest” is not what you think it is as it doesn’t apply to most investments.

Except most wealth (and wealth inequality) in Australia is inherited, not the product of hard work. You’re living in (rich) capitalist cloud cuckoo land.

Made my own money and inherited absolutely nothing.

Madbot is working late tonight; I’ll try again for a second time:

Still doesn’t alter the fact that most wealth in Australia is inherited.

And I’ll bet for all your hard work, you’re not one of the 11,000 with more than $5M in taxpayer-subsidised super, let alone the guy with $400M.

And why should you pay more tax on your hard-earned income than the lucky beneficiaries of a wealthy estate?

And are you saying people on the minimum wage are not also working hard?

And plenty of self-employed people work hard, take a risk, and fail, often losing their house into the bargain, often through external events beyond their control – the lottery of capitalism.

But all this is extraneous to the argument in this article – why should a taxpayer-subsidised retirement scheme increase inequality and in effect transfer wealth from workers to wealthy retirees (who have inherited much of their wealth) sitting on their fat posteriors so they can pass it on to their privileged offspring to enjoy while sitting on their fat posteriors, and lining the pockets of a bloated financial adviser industry in the process?

Death taxes (with a suitable free threshold that captured 95% or so of people) would have to be amongst the fairest of the lot. The only people having anything taken from them are already dead.

Yeah, nah. Saw the impacts of that when I was young.

Were there thresholds back then?Death taxes seem to work in many other countries without the sky falling in.

Yep. Why should you pay more tax on hard-earned income, and zip on being born to the right family.

Happy to make the call Lexus: death tax plus an annual wealth tax.

🙂

Until you get in the bracket where it affects you.

We’re not all totally selfish. Some would like to live in a more equal society.

Yeah. I’ve heard that before (until they are impacted) and then the tune changes!

I’m happy for more equality I just expect people to do whatever they can to achieve that rather than have it handed to them.

As I implied before, I am impacted and feel uncomfortable about the free ride we retirees get. I would like to see changes (including death duties).

Yeah, nah. I receive zero Government benefits and never have as an Adult. Paid far more than my fair share in taxes and worked too hard to get from poverty to just give it to the Government who will just waste it as usual.

You mean, handed to them in a big fat inheritance?

Anything actually. Unless you work for it yourself you really don’t appreciate it.

next, you’ll be rabbiting on about equality of opportunity.

Every one of us living in this SOCIETY makes use of the public infrastructure, and most of us pay our taxes for the benefits we gain from that use.

Some of us would rather invest in various methods of tax avoidance and minimisation such as super contributions and imputation credits and avoid paying society for the benefits gained from the use of PUBLIC infrastructure.

Yes, if you want order (rather than chaos) someone has to pay for it.

I suspect that I have paid far more tax than you have for my usage of PUBLIC infrastructure Sport.

Set the threshold at 95th percentile.

Multi-multi-millionaires crying about how they’re being hard done by are easy to ignore.

That much irony would probably kill a normal person. Not many purer examples of “having it handed to them” than an inheritance.

What would be the incentives for the ‘have nots” to get up and actually try and improve their lots?

I wouldn’t know about an inheritance as I have never received one.

It sucks being poor.

Unclear on what the relevance of that is, however.

Research years ago suggested the maximum income differential to create incentive in a competitive capitalist system was 9:1. That means the maximum income needs to be only about $450,000. So anyone ‘earning’ more than that is sponging off the rest of us.

One of the greatest myths of capitalism is that wealth is individually created. Wealth is socially created. You can’t become a millionaire living by yourself out in the bush or on a deserted island. You need other people to give you your millions.

Wrong- many countries have inheritance duties!! Why do you think inequality is growing??

You seem to have a problem with ex Public Servants- why is that???

Go to Sky after Dark; sounds like that is where your views belong.

Keep your insults to yourself.

Just because another country does something doesn’t mean that we have to do it.

I do dislike the Public Service in the extreme. Nothing more than a refuge for those who like to do as little as possible as often as possible.

You’re not the only one who’s worked hard, Lex. And be careful who you insult. The ‘Public Service’ includes doctors, nurses, social workers, cops, etc, who regularly work massive amounts of unpaid overtime in under-funded departments and hospitals keeping public services operating. Without their over-and-above-the-call-of-duty commitment, these public services would collapse because for the last 40 years neoliberalism has been cutting the taxes paid by rich individuals and corporations.

You acknowledge there is bathwater to throw out and you seem ok with that, but where is the baby you fear for?

Cannot see any ‘childish hissy fit’ in the article either. Just a robustly argued case for replacing superannuation, backed up citing supporting evidence; none of which you challenge and you seem to entirely or mostly accept. It’s argued for one point of view, rather than a disinterested presentation of views for and against, but that’s fair enough.

I can’t give you a simple answer.

I have been a life long investor. I have also been a core system lead developer on one of the largest and most complex Australian funds. So I know there are organisations built up over time and immense effort. They don’t magically appear. Trash them at your peril (always easy when you don’t know what went in and what is delivered). I had to understand the business.

Some super funds really do extraordinary work. To not recognise the value of this is either due to lack of knowledge or frustration leading to ideology first.

I am tired of revolutions, I prefer evolutions. But they take much more work to understand and write about. Readers might (understandably) not have the knowledge to process a more complex argument.

There is too much mixing of what is a responsibility of super and what is broader reform IMO.

I also know people who are up to their eyeballs in trusts, SMSF, farm discounts. So I can appreciate the intent of the author, but I don’t think it is a topic for revolution IMO.

What of value are they doing though ?

If it’s about choosing investments, then that value does not disappear if Superannuation does.

If it’s about managing assets within the Superannuation system, then it’s just a(nother) self-licking ice cream.

in the old days the knowledge base was held in the govt / community and was sent as a social program (e.g. pension). unfortunately the drive to privatise it has done little more than dilute the benefits by providing skim-offs for the rent-seekers. I remember the very rapid spawning of a whole industry that didn’t need to exist outside of that was there before. The great myth that privatisation will lower coast and increase efficiency. of course every privatisation of public services has resulted the exact opposite.

What revolution? What evolution? I see only devolution and extinction thanks to the dog-eat-dog, neoliberal ideology that underlies superannuation.

That’s not neoliberal ideology, that is nature.

That’s nature alright.

Adam Smith, the father of economics, knew human nature very well. He spoke of the greed and rapacity of man and stated forcefully that capitalists whenever they meet, for business or socially, end up discussing another method to increase profits. Smith declared that the market required government intervention through regulation to give the public an even break.

Smith also believed that wealth-getting is a vanity, NOT A VIRTUE.

Defenders of neoliberalism often quote Smith’s invisible hand, when talking of the supposed efficiency of “the Market” but did they ever really read Smith, or just grab the convenient bits?

Then again, that’s human nature and that is why more government intervention is required.

People who haven’t been life-long investors, or have had jobs that are as worthy as any other yet don’t pay well, or have dedicated their lives to being a volunteer or an artist or any other worthy contribution to society, deserve to have a comfortable retirements just like anyone else.

If the general public knew they would have a healthy pension waiting for them on retirement, they wouldn’t spend so much of their lives trying to acquire wealth, working themselves to death, and would have more time for family, friends and personal interests. This would no doubt create a happier society in the long run.

There is still a pension in Australia that everyone is eligible to apply for?

Retirees can still get a full pension with a decent level of super & income (e.g. about $275k for singles?)

If for any number of reasons, a pensioner doesn’t own their own home, it is impossible to pay rent and survive on the pension in much of Australia today.

Successive governments have converted a market for shelter into a market for investments and deserted the public housing space.

Single women over 55 are becoming the most common homeless statistic. That is a disgusting position for a first-world nation, as wealthy as Australia.

This debate about wealth-getting and personal rights is unseemly under the circumstances.

That’s now, for some or many, but not the future?

In, future demographic trends may not support same high rents and housing prices.

One struggles to identify what relevant expertise the author of the article has, IT? However, it presents mostly as opinion and supposed pro-employee ideology, without any data trends in support, while ignoring that scrapping super is a dream of many employers?

I’m recently retired and have about $250,000 in super. No house; I rent. That super allows me to survive in these times of cutthroat accommodation, and I think that that’s the baby referred to by Bill T. I think this is a good article, and deserves considerable discussion, but I am a little wary of the idea of pensions being the whole safety net for survival. Fine under a decent government, but Christ help us if a libertarian gets in.

Bullseye, hence my utter determination to try my best to not be in a position where I depend on someone else to provide.

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/centrelink/age-pension/robo-debt-now-terrorising-pensioners/

That Super will soon dwindle, especially under current inflation. A pension seems like a better safety net.

No, both, and later generations can expect to have more substantive super, but still have (part) pension to fall back on or supplement it.

The Govt pension fund that everyone working used to pay into and from which everyone, worker or not, was paid a pension, was eventually incorporated into general revenue, ie stolen. Pensions then became an issue because of the cost to govt, paving the way for super. Super is now so complicated that it is impossible for people like me to fathom it. This article does make it look pretty crook. Maybe any system starts out well but becomes contaminated later on, as cunning wanglers work on it. Witness age care, NDIS, my kids’ pocket money, etc.

Yes that’s a great point.

Always mystifies me that Joe Punter has to canvass the “Market” for quotes, or is forced into using a “Financial Advisor”, when the old system just had everyone covered by general revenue. Just another Liberal ruse to lower taxes for the wealthy and force the costs of social services onto the poor and middle.

The great argument against any system of pensions that the government has any sort of control over is that they cannot resist the temptation to keep taking funds for what ever they think is important (usually beneficial to them) at the time.

Even supposedly responsible governments do it. The German government at the time of unification virtually emptied the national pension bucket to help pay the costs of unification – some of which were little more than bribes to ‘ossies’ (East Germans) to feel good about the Christian Democrats.

A universal levy that goes to a national pension system is worthy – but it would absolutely have to be fortified against government action. Completely independently run.

Nothing is ever really “independently” run. The Government can and will intervene as circumstances dictate.

There are not separate “buckets of money” in our monetary system.

Money for expenditure is created as required, money received as tax “revenue” is destroyed.

Govt pension fund? Only for Public Servants I believe not “everyone”. The Future Fund was established to fund the overly generous public service super funds (instead of consolidated revenue). The Commonwealth Age Pension has never been a “funded” pension to my knowledge.

a buddy of mine (age ?70yrs) constantly speaks of the times when he was working and the pact where taxes collected were designed to provide an aged pension.

I am sceptical of his version of events, but have always lived in the hope that, if needed, one could be paid an aged pension.

That’s like the promise that Fuel Tax would only be used for road infrastructure. Didn’t happen. Remember the Future Fund was initially conceived to fund the unfunded pension benefits of our sainted Public Service. That has since been expanded by successive governments.

I firmly believe that it is up to individuals to take responsibility for themselves and not rely on the Government to “look after” you in retirement (obviously not everyone can do that). Basically, you limit your income and choices in retirement if you do so. I don’t know anyone who relies solely on the Age Pension that is having a good time in retirement.

One of the points in making it overly complicated is to facilitate the skimming of money off the top by middlemen who otherwise contribute nothing of value.

You’ll see the same thing in most privatised services. Health insurance (masquerading as healthcare) is another textbook example.

Advice is not “nothing of value” and needs to be paid for.

And what, pray tell, is your virtuous occupation?

LOL. As if most people in the FIRE industries are giving advice “worth paying for”. It’s either boilerplate waffle on investing and retirement or how to take advantage of quirks and weaknesses in the system.

And that’s before even considering the vast majority of people do SFA to actively managed their super.

The vast majority of the financial services industry exists to a) solve problems it created and b) help the already wealthy exploit the system to get even wealthier

Though to be fair the catastrophic garbage fire of private health insurance probably beats out superannuation given it only exists to profit from making healthcare more expensive and harder to access.

Experienced in those areas are you? Legally qualified to give advice are you? Willing to pay for sound advice are you?

The latter is the most relevant point. You get what you pay for when it comes to anything but particularly when it comes to professional services.

A ‘Dr’ of something….

Nothing useful I suspect.

You may have not noticed but beyond the dog whistling of temporary resident churnover of international students etc., we have an ageing population with increasing dependency ratios; if everyone was on a pension it would crash budgets in future.

That’s why we have super but opposed by the libertarian right, maybe that’s the objective?

“now so complicated that it is impossible for people like me to fathom it” – RUBBISH!!!!!

of course the super system takes some effort to understand, and like anything else which is worthwhile, understanding will grow with time. Your assertion that it is impossible to understand illustrates laziness, thoughtlessness and jumping to conclusions – hence your assertion is absolute rubbish.

back to Drastic, you said “for people like me” – well help us readers to make an informed judgement…please expand on “people like me”

‘Christ help us if a libertarian gets in.’ this is exactly what they have been quietly pushing for, sabotaging super and SCGs for employers; the article is astroturfing for the ‘libertarian trap’….

Agree. It’s the tax breaks (especially the Howard era ones) that need to be fixed. To be fair to Labor, Shorten proposed a step in the right direction but got hammered by the MSM. As a self funded diy super retiree myself, the tax breaks esp refunded excess franking credits are ridiculous

As a part of fixing the tax breaks there really needs to be a major reform of Howard/Costello’s treatment of Self Managed Superannuation Funds which created a massive tax shelter vehicle for the rich & encouraged speculation in real estate.

What “speculation in Real Estate” do you refer to?

The mass purchase of domestic housing by investors, using the tax breaks from their self managed superannuation funds, which advantages them over those simply wanting to buy a house to live in

Evidence please. This is another claim that emerges without any evidence to back it up (a bit like the Foreign Investor furphy). Investments in real property can be made by SMSF’s subject to a range of restrictiins:

The general SMSF property rules include:

The property must meet the ‘sole purpose test’ of solely providing retirement benefits to fund members.

The property purchased must not be from a related party of a fund member.

The property can not be lived in or rented by a fund member or any related parties of a fund member.

If purchasing a commercial property, it can be leased to a fund member or related parties of a fund member for their business – as long as it is solely used for business purposes. However, it must be leased at the market rate and follow specific rules.

Additionally, along with the above, any investment property needs to be consistent with the investment strategy and risk profile of the fund. Super Funds also cannot borrow

Real Estate is no different to any other investment in reality. I know very few SMSF’s that own Residential Property but plenty that own Commercial Property.

Obtaining a home loan using a SMSF to buy property involves very strict borrowing conditions. All SMSF home loans must be taken using a limited recourse borrowing arrangement (LRBA). To “limit the recourse” of a lender, an LRBA involves establishing a separate property trust and trustee on behalf of the super fund, outside of the SMSF structure.

All the income and expenses of the property go through the super fund’s bank account and the super fund must meet all loan repayments. If the super fund fails to do this, the lender only has the property held in the separate trust as recourse, and therefore cannot access any remaining assets of the super fund.

The key risks that you should be aware of are:

Compliance costs: SMSFs need to value all of their assets at market value, and the valuation needs to be based on objective and verifiable data.

Higher costs: Loans using SMSF can be more costly than other property loans.

Cash flow: When buying property using SMSF, your loan repayments must come from your SMSF’s bank account. Therefore you will need to ensure your fund always has sufficient cash flow to meet repayments.

Difficult to cancel: You are unable to unwind the arrangement for a SMSF property. If there is an issue with your loan documents and contract, you may have to sell the property, this can potentially cause substantial losses to your SMSF.

Possible tax losses: You are unable to offset tax losses from the SMSF property with taxable income outside your fund.

Commercial property tax considerations: If you’re investing in a commercial property and your earnings are in excess of $75k you are required to register for GST.

Capital gains tax considerations: If you choose to sell the property you will need to ensure the appropriate capital gains tax is paid.

No alterations to the property: You may undertake normal repairs and maintenance to the property, however, under the LRBA rules, improvements and renovations are not allowed. Any maintenance or repairs made cannot result in the property becoming a new asset.

You may recall that Albo was trying to get Super funds to invest in housing for rent to lower income people and not getting any traction. I wonder why.

People with SMSFs invest in real estate as assets for their funds, is what I understand the situation to be. Happy to be corrected.

I know what she means but she has some illusions on this happening. My reply is “awaiting approval” as it is comprehensive.

*delusions

The problem with the existing system of super is not that earnings are-with a concessional rate of tax meaningful only to those are taxed above the concessional rate-deposited in individual accounts in proportion to the funds held in those accounts. First, governments have changed the rules over the years for many member funds since super was set up, so that the system increases inequality among wage earners. Second, they have introduced individual private funds that enable those few whose earnings are largely from capital to have concessional rates of tax from specified forms of investment. Third, our system is plagued by the neoliberalism that Hawke and Keating introduced. Many providers were allowed, whether Union industry funds or Privately owned funds, such as those owned by the banks. This was to reap “efficiency” benefits from competition, which is the “proper” way to get these, according to neoliberalism, although other means are possible.

These features of the system rather than individual accounts account for its tendency to increase inequality among wage/salary earners. The elimination of for life pensions reflects increasing insecure employment, making it easier for employers to sack people. Earnings could be deposited at varying rates per individual holdings, with those with less getting a bigger share per holding dollar from those earning more. Waster could be lessened by eliminating faux competition.

But, hey, in our capitalist society, whose going to do that?

Super is also about dealing with demographic decline in the future so as to not have all (increasing numbers of) retirees tugging on budgets….basic maths unless one focuses upon now.

Suspicious, as to why the LNP have not been cited and their constant attempts to have or allow higher income or wealthy types manipulate their super for lower tax thresholds?

Plus, by coincidence, nobbling super especially increasing the SCG, falsely describing as a ‘tax’ and calling for super’s scrapping?

Yes, that stuck me too. I was very wary of the strange focus on the ALP and scrapping before adjustment.

The unfunded pension liability likelihood just didn’t get a mention.

I am really surprised at the level of trust of some of the readers. Any large pot of money becomes an overwhelming temptation for a government in hard times. There are so many cases of set aside funds being raided.

It’s possible that PJK tried to firewall off this sort of government grab.

I disagree very strongly with this argument. Having served as a nun in a religious order until I was 47 years I became employed for the first time in paid employment. It was in community work and not highly paid in spite of my qualifications. Over the next 15 years my partner who also worked with the disability community saved, bought a home and placed everything extra into an industrial superfund. Now in our mid seventies we are self funded and live off the superfund. They have low fees and have earned very well and grown over the ten years we have lived from them. I know mortgages are now very high and wages have not grown but we began in late 40s with nothing.

Congratulations on where you got to in such a short time. Just a couple things. Qualifications are irrelevant in reality. You are paid for what you produce (and how that is valued). Sad but true. Mortgage rates are still low in comparison with past decades despite what you read and hear.

Good on you, well said I also see this positive change for individual people.

The imbalance is staggering. Wealthy Australians tend to prefer the self-managed version of superannuation where they have much greater freedom to use the fund however they like. Assistant Treasurer and Minister for Financial Services Stephen Jones said last November, ‘We have 32 self-managed super funds [each] with more than $100 million in assets – the largest self-managed super fund has over $400 million in assets.’

Stephen Jones has identified the target; just legislate upper limits and index them to inflation. Leave the average person and their hard won Super alone.

“use the fund how they like”

You clearly have no idea on SMSF’s and how they operate. They operate on the same Regulations as any Super Fund with a few extra restrictions. They certainly can’t “use the fund how they like”. If anything, they are under greater scrutiny than “standard” funds as the ATO are the Regulator.

SMSF users primarily have SMSF’s to have more investment control than they would in the usual funds. This means they have to, you know, actually be involved in the Management and Administration of their Funds as the Trustees carry the can for investment performance and any Compliance failures. Responsibility cannot be outsourced in SMSF’s.

… is exactly what I mean by greater freedom to “use the fund how they like”. If they did not get that greater freedom, and get such benefit form it that it is worth the trouble, why on earth would they bother?

It’s called “investment selection”. They still can’t invest in anything they feel like. They must have a documented Investment Strategy with investment return objectives, the investments need to meet that strategy and must be reviewed regularly.

If you don’t understand SMSF’s you might want to read up on them.

The preceding words you removed when you selectively quoted me fully account for the point you are trying but failing to make. It’s standard English and not difficult:

greater freedom ≠ complete freedom

Hope that helps. Your (wilful?) inability to comprehend standard English ≠ any problem with my understanding of SMSFs, which so far is identical to yours.

Nice try. I honestly doubt that you have any knowledge of SMSF’s (or super in reality) if you think that Trustees have “Complete Freedom” and “can use the fund as they like” (your exact words not mine) . Your attempt to try and claim that what you say isn’t what you meant proves that your “standard English” isn’t up to par.

FYI. Greater freedom means exactly that not “Complete Freedom”. In an SMSF you can choose the underlying actual Investments in whatever investment sector. In other funds, you select the investment option with the Asset selection performed by the Investment Managers for the Fund. SMSF’s still have to comply with the Investment requirements of the SIS Act and Regulations.

You clearly don’t have any knowledge of the SIS Act and Regulations that govern all Superannuation Funds including SMSF’s.

Perhaps you may find this useful as a start:

https://www.ato.gov.au/super/self-managed-super-funds/investing/

You are for sure being deliberately obtuse, and you are also traducing me by claiming to quote my exact words when you are selectively editing them and making things up.

This, written by you, is complete rubbish:

What is the matter with you? You keep insisting I know nothing about SMSFs when there is no difference between my understanding and yours, so far. By insulting me you insult yourself.

What is the matter with you?

What I wrote is what you wrote.

I object to your original claim that “Wealthy Australians tend to prefer the self-managed version of superannuation where they have much greater freedom to use the fund however they like.” (and yes that is what you wrote).

SMSF Trustees are subject to the same restrictions as other funds and can’t do with or invest invest the fund however they like.

Do they have more leeway as a Member to influence investment decisions and investment selection? Yes.

Can they use the fund however they like? Absolutely not.

Simple as that.

I have had to clean up the mess from a few idiot Trustee’s that actually believed (what you state) until such time as they encountered me and reality came crashing down.

Not trying to insult you however your choice of words implies that with an SMSF, Trustees can do and invest however they like.

They cannot do so.

Understand the difference?

You see – you are getting there. This time you’ve quoted the right bit in full, including the words about ‘much greater freedom’. You did not bother to underline them, but they are the words that make what I said correct.

You continue by pointing out

Yes, there are restrictions. Yes, they cannot invest ‘however they like”. Nothing I said says otherwise. None of this changes the fact that a SMSF gives greater freedom. Why do you imagine anyone chooses to self-manage? What motivates them? (Nothing but masochism, apparently, judging by your heart-breaking description of the horrors they endure by choosing this option. Ha ha, no.) Just ask yourself why these funds are called ‘self-managed’. The clue is in the name.

You are still not getting it. You missed the point and your English is still not up to par.

“.. where they have much greater freedom to use the fund however they like.”

” Nothing I said says otherwise.” Yes it does.

Can they use the fund however they like? Absolutely not.

The key words in your sentence are “use the fund however they like”. Completely incorrect. They cannot “use the fund however they like” whether they have “much greater freedom” or not.

As to why people have SMSF’s the reasons are myriad. Having been heavily involved with SMSF’s for over 30 years on a professional basis (including training Trustees, Administrators and Advisers), I can assure you that many are the victims of greedy Accountants who are barely able to spell “superannuation” but love accounting fees.

I agree that they can be too much trouble if you are not prepared to learn about Trustee Responsibilities, understand Compliance with the SIS Act and Regs and be prepared to put the time and effort into it. There is nothing “Self-managed” about SMSF’s despite the name. They were originally called Excluded Funds.

Better than watching the tennis – thanks!

Cheers. I aim to please.

That assumes no remedial political action will and/or can be taken on super funds, esp. inc. SMSFs in short-medium term and that this -/+ ve PR focus on the now or present ignores trends of demography (maths 101) and ‘the time value of money’ (Finance 101)?

So true! Superannuation is a dog, with fleas, lice, worms and mange. All superannuation tax concessions should be stripped away.

One, if as claimed those massive superannuation tax subsidies don’t actually cost anything, superannuants lose nothing from ending them.

Two, since superannuation is supposed to be profitable in its own right, it does not deserve a subsidy.

Three, voluntary superannuation tax concessions are brazen looting of public revenues by wealthy working rent-seekers with a Culture of Entitlement to having their snouts in the trough. Yet they do virtually nothing to reduce demand for the Age Pension.

Four, although Right-wing columnists assert a minimal cost, that cost – both the cost of budget subsidies, plus the employer capacity to force offsets of compulsory super against workers’ already stagnant wages – is increasing substantially.

Five, the Gold Standard is the unfunded, entirely governmental Age Pension. It is not only regular and reliable, but nearly every retiree will still be relying on it regardless of scale of Cheating’s and Costello’s kingly subsidies!

Six, as everyone’s hero Scott Morrison said, it is important the system supports those who need it and respects those who have to pay for it. It doesn’t.

Seven, the weakest and poorest workers are often forced by their employer to pay for it out of their wages.

Eight, the massive tax giveaways subsidise the most obscenely wealthy retirees much the most, the poorest retirees not at all, exactly as Howard et al intended. Their $42 BILLION a year could fund nearly a doubling of the Age Pension (all such income supports totalling $53.8 billion in 2021–22).

Perhaps just scrap super and give retirees a $50,000 lump sum rising according to their age – it would be far cheaper! Perhaps we could have a few investment seminars run by Timbercorp investors to promote the idea of financial simplicity in ones’ old age.

“Two, since superannuation is supposed to be profitable in its own right, it does not deserve a subsidy.”

See also: private health cover and private schooling!