“Go home,” Kitahna Abbott yells at a group of six young kids a couple of hundred meters away.

She’s unfazed when the kids take off in the opposite direction and keeps walking with four other Arrernte foot patrollers. Crikey has tagged along for what is just the second night of the Mparntwe Alice Springs Traditional Owner patrol, and at this stage, at 8.30 at night, Abbott says it’s enough to just make themselves known.

“Let them have their fun. Then we’ll tell them to go home,” Abbott tells Crikey.

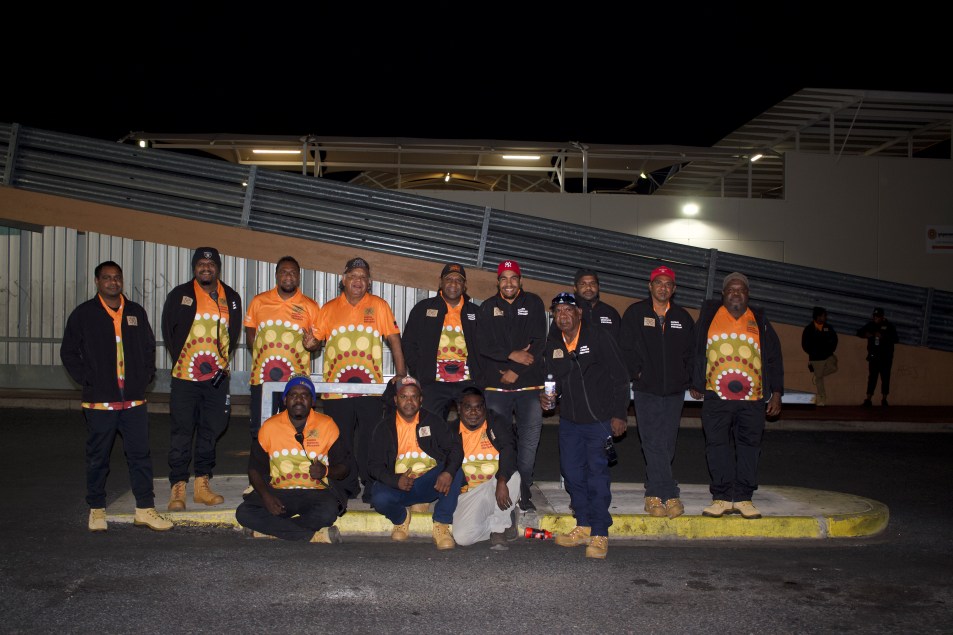

Abbott is a 22-year-old Arrernte woman and one of 25 patrolling the street Tuesday and Wednesday night — in either car or on foot — as part of the new Lhere Artepe Arrernte-led Traditional Owner town watch. The group of 18 men and seven women aged 20 through 60 all wear orange shirts and desert boots, with jackets and beanies on hand for when the night turns cold.

“Jumpers off, jumpers off, you mob need to show the orange,” team leader Phillip Alice instructs them before they head out.

“You mob all got to look smart. We are leaders. People will look up at us. This town’ll be seeing orange,” he says.

The former police officer (25 years in the force) is now at the helm of the new patrol program run by Lhere Artepe, the registered and recognised body representing Native Title Holders of Alice Springs. It’s the product of a two-year $900,000 grant from the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA), but Alice is confident: “This patrol program is gonna go forever.”

The patrol was established by Traditional Owners in response to youth “running amok” on their Country — the town of Alice Springs. The town has garnered international media attention, while domestically politicians from both sides of the fence have chimed in (and flown in) to use Alice Springs as a case study for increased law and order, alcohol bans and a Yes-No campaign for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

For Arrernte Traditional Owners, “enough is enough”. Alice says he is sick and tired of non-local troublemakers coming into town and “putting us to shame”. The new patrol program is their way of restoring order and respect for their people, culture and Country.

“They need to understand Alice Springs, Mparntwe, is the land of Arrernte people. You come here? You respect our land,” he says.

“We don’t go run amok on your Country. So you need to understand that this is our Country, Arrernte Country. We as Traditional Owners will lay down our lore, Aboriginal lore, l-o-r-e.”

How will the patrol program work?

Half of the $900,000 government grant has gone into set-up (four vehicles, secure line two-way radios, clothing and other equipment), leaving the rest of the budget to fund patrols Tuesday through Saturday, 12pm to 3am, 12 patrollers by day and then again by night. With bottle shops closed Monday and Tuesday, and Sunday deemed a quiet day, Lhere Artepe’s plan to man the town and surrounds — shops, car parks, toilet blocks, football oval, suburbs, the route along the river — is the product of lengthy consultation with stakeholders and services on when and where they’re needed most.

The program will also make heavy use of data, with Lhere Artepe aiming to collect the names, ages, addresses and community IDs of all “troublemakers” in town.

Initially, this will be done manually, but the rollout of a public-facing app in May will automate much of the process. The app will allow anyone and everyone to report incidents in the town. Rather than triggering a triple-zero police response, alerts will go directly to Traditional Owners. The Lhere Artepe headquarters will host a live dashboard with location data of reported incidents and the whereabouts of all Arrernte foot and vehicle crews, allowing for easy dispatch.

“We want to know where these troublemakers are from. If they’re Arrernte, we can discipline them. But we can’t discipline people from another Country. That’s where the referral program comes in,” Lhere Artepe CEO Graeme Smith says.

During the night, the role of Traditional Owners will be to act as “first respondent” and “interpreter” to the full suite of police, security, housing, youth services and paramedics.

Every evening at 7 o’clock, all these night-time operators convene outside the police station for a briefing. Each party chimes in with how many vehicles they have on hand, where they’re patrolling, and what time they’re on until, as well as any relevant incidents from earlier in the day. The resounding sentiment on day one was: “It’s really good to see you here.”

Off the streets, Traditional Owners will also be heavily involved in “black fella to black fella” follow-through. While kids (and adults) will be funnelled through existing social services, Smith says if the same names keep popping up, they’ll know that referral is failing.

“If at the end of the day, they’re still problematic, we call them to a meeting and say please explain your ass. We call their elders and those who know them to help us find the answers. Then we’ll take our elders to go out to talk to their elders and sit together in the dirt, black fella to black fella.”

Smith wants to stamp out the come-go, do-as-you-please attitude that he believes exists in Alice Springs. He says it’s not present in other communities where cultural protocols dictate that a guest “behave or get out”. The right to evict someone and “return them to Country” lies in the hands of elders.

“If it’s ground-breaking, then it should be,” Smith says. “Ground-breaking for the Western world maybe, but it’s not ground-breaking in cultural practice. That’s what we do. It’s been happening for 60,000 years.”

Out on the town

The patrol launched on Tuesday night with a team of 25 patrollers (upwards of 40 Arrernte people have already signed up). Smith decided to set aside the 12-person cap in favour of establishing a “presence” in the town. He says the numbers were necessary for “immediate impact”.

“They need to see us. They need to know we’re here.”

And they did. Throughout Alice Springs, construction workers, police, security guards, locals and visitors all commented to Crikey on the force of orange and what a welcome sight it was.

When it came to troublemakers, Eastern Arrertne woman and female team leader Bianca Turner said that little introduction was required: “They know who we are.”

“They saw the orange shirts. Their little eyes were popping, they didn’t know what to do,” she said.

For Traditional Owners, visual authority comes hand in hand with being heard. In his pre-patrol briefing, Alice instructs patrollers to be “loud” and command respect for their Country and cultural protocols through their voice.

“Your voice is your power,” Alice says. “You mob mean business by talking to people. When you mob see a group, you go to them. You tell them we got this Arrernte patrol. Come down hard with your voice.”

Whether that means telling kids to “get off the street or I’ll break your socks in half” or to “go home, it’s cold, town is not for you”, Smith was clear that Lhere Artepe had no plans to roll out a playbook telling patrollers “how to patrol”.

“I’m not gonna tell them how to do their job. You’ve got to allow them the judgment they have as Arrernte people. We are the authority,” he says.

This message was made loud and clear to patrollers on night one: “Use your cultural protocols. Lhere Artepe will back you. With lawyers, with money, with clothes, with food, whatever you need.”

“You mob got freedom to run the streets tonight and every other night,” Smith tells them.

The program is about fighting culture with culture, in a way that Traditional Owners say the Western system cannot. As Crikey walks around with Abbott and the foot patrol, she points to the group of kids who took off.

“I used to be one of those kids. You know, teasing the cops, running amok, playing chasey. But when I saw my young nieces and nephews doing the same, I saw the damage it was doing to mob. I started telling them don’t do that. I started telling them to have respect,” she says.

“Having responsibility is power.”

For the 22-year-old mother of one, this is her first job. She’s here for work as much as she is to clean up the reputation of the town and help keep Indigenous kids safe and off the streets.

Like many of the patrollers that Crikey speaks to, their identity as Arrertne people and their ability to speak language (not just their own) are what they hope will be the program’s deadliest weapons.

“I know a lot of people and a lot of kids. There’s lots of them, but there’s more of us. We’re all Aboriginal, and we all speak language,” Abbott says.

“That means we understand where others can’t.”

Finally, the indigenous having the paternilistic white man failed “solutions” put aside, as self-evident failures.

This is wonderful. The beginning of a hew era. New hope. Small steps.

Brilliant effort. I wish them all the best with this program. Also, ‘explain your ass’ and ‘or I’ll break your socks in half’. Mob have THE best turn of phrase.

This should’ve been organized years back. I have a feeling it probably was, but funding tends to dry up when a problem is seen by the politicians to be ‘solved’. There are a lot of different mobs converging on Alice Springs and the Todd, many from dry zones. Traditional protocols, as Alice points out, have been ignored for decades, probably because the drinkers and mischief makers see the place as a white town, not as Land. Best of luck reclaiming Arrernte turf, and don’t let the whitefellas defund you when they want the money to go elsewhere.

What a great program. Good luck to all involved.

PS – I hope Crikey can continue to keep us updated on what I’m sure will be a successful program.

Good fortunes to you all. Well done. A similar concept operates in my homeland. The Māori wardens, who also patrol communities and who also help at events. Care for our youth is a paramount task. Prevention of them getting sucked into the criminal justice merry-go-round can have life long benefits. I’d encourage more folks to consider joining or supporting this initiative. Kia Kaha (be strong)

I’m from the Shakies too. The Maori Wardens are awesome. Rangatiratanga plus mana equals success over many decades.