“The pressures on the budget are acute,” the treasurer told the nation last week, his silhouette briefly shielding the dour prime minister sitting behind him. “But as a Labor government, we will always strive to help those who need it the most. That’s why, tonight, we announce a $40 per fortnight increase for JobSeeker recipients.”

“Hear, hear”, was the murmured response to a tweak that does nothing to silence the drumbeat of poverty immiserating thousands across the nation.

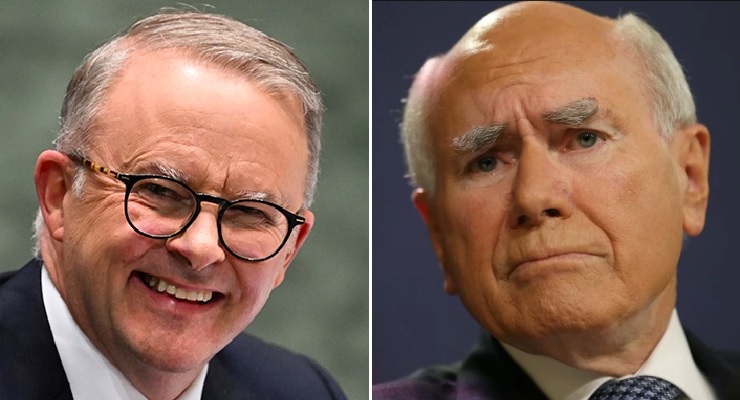

There was, on any view, something deeply disquieting about Anthony Albanese’s fixed grimace as he observed Treasurer Jim Chalmers engage in one of several acts of classist sophistry on budget night. At the time, it was unclear whether this grim resolve, redolent of someone sitting in a dentist waiting room, was the product of some practised expression of seriousness designed to reflect the weight of the occasion. Or whether, on the contrary, it was emblematic of some haunting prick of conscience — a sense that this particular philosophical failing was one too many.

After all, the consequences carried by the cascading tides of inequality and generational betrayal promise to outlive us all if Albanese’s government is all that confronts them.

The word “poverty”, for what it’s worth, received but one mention in Chalmers’ budget speech. “Inequality” did not feature at all (though it’s not impossible to glean oblique references to it in the form of the $14 billion over four years cost-of-living package, and its $3 billion pay rise for aged care workers) while the term “class” or “class warfare” manifested only in the form of that unspoken pillar upon which much of the 2023-24 budget rests.

Left untouched, in this connection, was the suite of unearned tax benefits and concessions that accrue almost uniformly to the winners in all budgets since the dawn of John Howard’s government: the wealthy and (some) older Australians.

There was no mention of changes to franking credits, negative gearing, capital gains concessions and superannuation perks — all of which combine to drain the public purse of some $85 billion a year and add immense pressure to an overheated housing market.

Nor was there any reference to the seriously ill-timed $11 billion per year tax increase for low- and middle-income earners, and still less would the government be drawn on the slated stage three tax cuts for the wealthy, the cost of which was this week revised to more than $310 billion over 10 years.

Perhaps the raw or unvarnished significance of such figures only intrudes when it’s remembered that the $40 per fortnight increase to JobSeeker and like payments will cost less than $1 billion a year — some $5 billion short of the increase recently recommended by the government’s own economic inclusion advisory committee.

None of this, of course, was surprising or even remotely unexpected. The solidifying wisdom among Canberra pundits is that this is par for the course for a “softly, softly” government bent on fashioning itself with a Hawke-like pragmatism moulded to the times. Having spied an opening in the centre-right lanes of politics vacated by a fringe opposition, Albanese is intent on rendering Labor the natural party of government, one that is conspicuously uninspiring, not inspiring; cold rather than bold. Hence the common refrains of “modest change” and “responsible government”.

One variation of this narrative — and one that most true believers cling to — would have you believe this so-called “small-target” political strategy doesn’t necessarily involve any compromise of traditional Labor values. Taking this long view two weeks ago was The Sydney Morning Herald’s Sean Kelly, who suggested the federal government, the nation’s most important storyteller, was using the budget to show Australians it is “doing many things” but “can’t afford to do everything” — though hold tight for the sequel.

“This government has mastered the art of doing just enough for the doing to be worth something, but not so much that any particular element takes over,” Kelly wrote, citing the minor change to the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax as an example. “It will annoy the gas sector; the left will want more. The key point is that most people, probably, will not notice.”

As an approach to politics, “small target” implies a strategy of defence rather than offence — a government, in other words, intent on securing successive terms at any cost. And this is why, suggested Kelly, we’d be hard put to hear anything about stage three tax cuts anytime soon, or at least until the inevitable economic winds of change compel a comfortable shift in the tenor of debate.

Except, of course, Kelly was proved wrong within 24 hours of the budget’s release. Not only had Albanese taken it upon himself to talk about the stage three tax cuts, he had opted to actively sell them to low- and middle-income earners as though the dismantling of the country’s progressive tax system is a cause for celebration. On any view, Albanese’s self-serving implication that these households stand to materially benefit from the tax cuts was a brazen lie, as recent PBO analysis confirms, and yet he was undeterred.

As leaked government talking points reveal, he’s also steeled his lieutenants against even countenancing changes to negative gearing, while Chalmers, for his part, expressed a fondness for that distinctly conservative aphorism that the best form of welfare for the unemployed is a job — never mind that JobSeeker ensures a level of destitution so acute it acts as a barrier to employment.

The most charitable explanation for these developments, short of shockingly clumsy politics, is that Albanese is attempting to fend off predictable lines of attack from the opposition and a willing right-wing press that sees truth in analyses such as Kelly’s. But even if that is so, and it’s questionable whether it is, such rhetoric plainly leaves the government in a catch-22 with little to no room to manoeuvre in the future.

The competing reading is that Albanese’s actions were by design in every sense of the word. In a bid to hose down suggestions of looming progressive reform, he’s not so much channelling the pragmatism of Hawke as he is embracing Howard’s “comfortable and relaxed” Australia: one in which there’s opportunity for some but not for all, where the rich continue to get richer and the poor poorer, and one that safeguards the wealthy’s sense of entitlement but forsakes the nation’s broken social safety net.

It’s an Australia, in other words, which no longer holds to the twin ideals that the lives of the next generation are destined to improve because the moral arc of democracy pulls inexorably towards progress.

It’s from this vantage point that the full significance of Albanese’s rhetoric around trust in politics emerges. Plainly, he tells us, he was being honest when he said his government would not hold the so-called aspirational class back, ergo his refusal to entertain the possibility of winding back policies that favour the rich and prejudice the poor, the young and middle Australians.

By contrast, the notion his government would “leave no one behind” was more of a vague “non-core” promise emblematic of Howard’s style of political mendacity. Much the same can be said of the contrast laid bare by Albanese’s pledge to properly address the housing and climate crises — non-core promises — and his absolutism on the half-trillion-dollar AUKUS deal — a core promise, notwithstanding its hazy and potentially dangerous parameters.

The difficulty with refusing to relinquish comforting narratives such as Kelly’s is that it enables the approach taken by the government to escape the censure it deserves. It also shields from view the thorny contradictions which reside at the heart of some of the government’s signature commitments and achievements, such as the Voice to Parliament referendum alongside indefensible funding cuts to Aboriginal legal aid centres. Or its laudable childcare policy, the generosity of which curiously extends to families earning $500,000 but excludes those 126,000 children whose parents subsist on the bottom rung of society. The list goes on.

By some distance, the most pressing concern attending Albanese’s approach, whichever way you look at it, is that it conceals what is in truth a profoundly radical agenda. There’s no doubt, for instance, Howard’s skilled approach to politics was, with one or two exceptions, singularly regressive for the nation’s welfare. Likewise, there’s no doubt Albanese’s refusal to stem the tides of inequality arising from that era, and indeed his intention to festoon the country with tax cuts which jettison one of its last vestiges of fairness, risks replacing faith in democracy with an abiding and dangerous cynicism.

The great Albanese lie, in other words, is that doing little to nothing of great significance as time marches on is “responsible”, when in reality the swirling forces of inequality are such that the converse is true, as evidenced by the calamitous return of Dickensian diseases in the United Kingdom.

Naturally, those who endorse Albanese’s approach bristle at this analysis, pointing out his political calculations largely owe to a hostile media. The problem with that rejoinder, however, is that it ignores the object lesson of the Andrews government in Victoria, which has exposed the depths of Murdoch irrelevance. It also pretends Albanese is oblivious to the significant political capital afforded by an exquisitely appalling opposition, when — as his association with Kyle Sandilands and his bizarre sledge at Lidia Thorpe’s mental health attest — that is plainly untrue.

Indeed, in the days after the budget, Albanese reminded a gathered crowd, with his usual languorous inflection, that Labor will not “leave anyone behind”, only to interrupt that cadence with a rousing crescendo of: “But nor will it hold anyone back!”

As impressions go, this wasn’t some random soliloquy or trace of indiscipline as much as an emphasis of where his government’s true priorities lie. All of which is why it was probably wrong to read Albanese’s seeming twitchiness on budget night as indicative of man caught between his ideals and political reality, as opposed to a man intent on holding power for power’s sake.

As things stand, Albanese and the words “disappointment” and “class traitor” will, in all likelihood, one day stand adjacent: an undignifying emblem of a man who has spent much of his public life espousing progressive politics.

After all, true political moderation at a time of such hopelessly pressing need was always going to count as a misdeed. But radical conservatism donning the costume of moderation is gaslighting of the highest order.

Is it fair to compare Albanese’s government to the one run by John Howard? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Yes, indeed, Maeve.

Albanese’s government and policies have, in the name of caution, severely shattered the hopes and support of many progressive voters who voted for serious change to more equitability and fairness in the interests of a safer and more secure Australia. (And the great crime of AUKUS has nothing to do with security).

A huge disappointment.

Albo is basically a careerist old fart with four houses, who has been in parliament for nearly 30 years and none of these problems are going to progress while he is still in the drivers seat. Hey Ho, Let’s Go indeed.

The delight I felt when the Coalition lost the election had turned to huge diappointment. I wonder what his mother, if still alive, would say at this abandonment of Labor’s usual work on behalf of the downtrodden to the now bolstering the wealthy? Is it having four houses and a young ladyfriend that has turned his head, and now wants more of the goodcstuff for himself, which he would get in bucketsful if he does keep the tax cuts for the wealthy?

I think what Albanese is doing, unintentionally of course, is pave the way for a huge swing to the Greens.

I think you are right. The LNP might lose some more seats to the Teals and Labor will lose them to the Greens. We might just end up with a Parliament that does what people want.

We’ve been here before, of course – the elusive promise that is the Greens. Unfortunately they seem entirely content with their 10 to 14% of voter’s preferences. Been this way forever. I’d love them to become the main contender as a centre left leaning party and put well deserved pressure on Labor but reality tells me they just do not want to be major players.

The increasing yoof vote should help.

Increasing your vote with nearly the entire media and political establishment trying to prevent it is difficult.

You can take the boy out of the housing commission home, and apparently you can take the housing commission home out of the boy too.

Labor’s “rusted-on” supporters are the 1%’s “useful idiots”

Albo is more than a class traitor, he is betraying every human who understands the horrors which the dying days of capitalism will reek on our planet

Wreak

Present tense of wrought

The problem is that Labor long ago became a top down party. Without a mass base supporting social change, it lives in constant fear of offending key groups identified by its pollsters and tacticians.Someone should also tell Albanese that no matter what contortions a Labor government does. It is only tolerated as long as the ruling class lacks unity and a successful vehicle. If they have to replace the Liberal Party,they eventually will.