A Cranbourne family arrives at a Rubicon campsite to find a thicket of blackberry weeds adjoining a power station. A park ranger’s job is reduced to cleaning toilets. A Preston couple can’t find a parking spot at Warburton, where traffic to Mount Donna Buang is choked, and a bike trail plan divides the community.

Outside Olinda Falls, a cyclist swerves around cars banked on the roadside. Decayed interpretive boards baffle foreign students at Badger Creek, with one Facebook user describing the facilities as “a disgrace”.

These are scenarios experienced by weekend visitors to Victoria’s forested communities, where a parks deficit is dividing towns, accelerating ecosystem collapse, increasing bushfire threats and wedging bush users against one another.

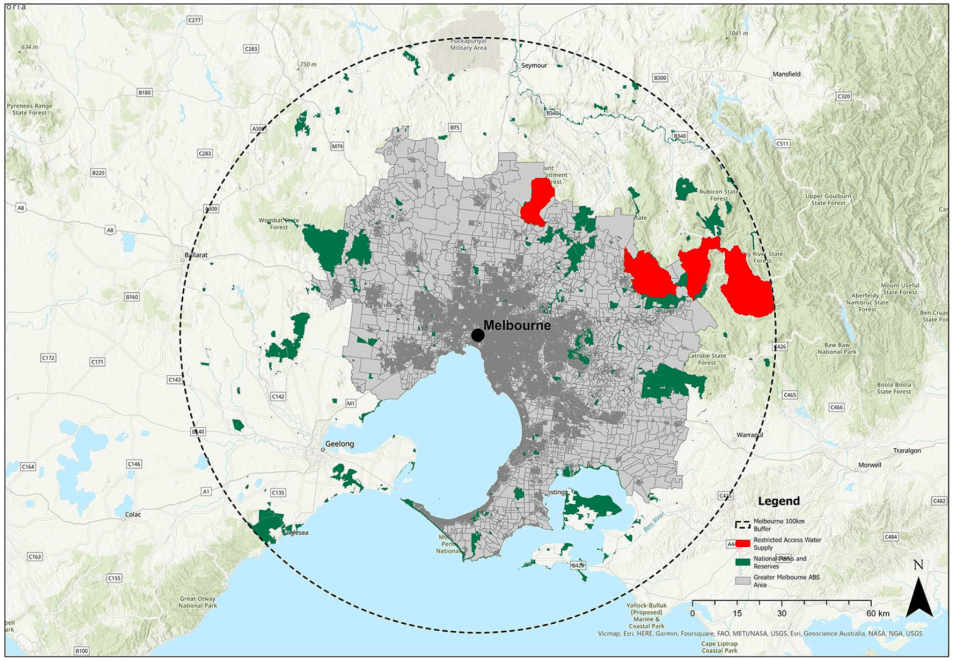

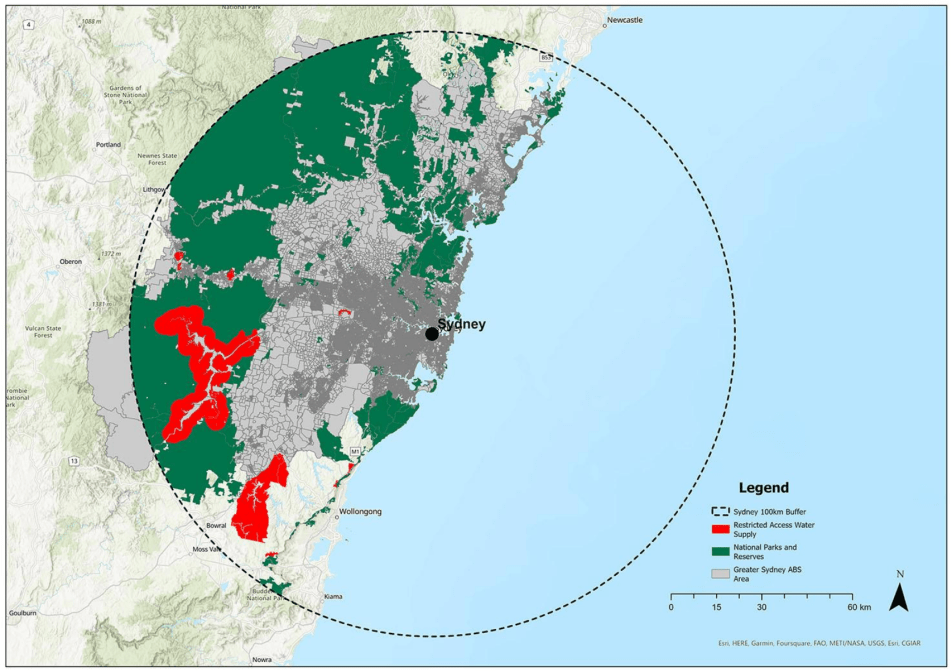

As research mounts confirming the health benefits of nature exposure, Melburnians are being channelled into parks designed in the 1990s for a population that has since more than doubled. While Sydneysiders enjoy several million hectares of integrated forests within an hour of the CBD, Melburnians can experience only fragments in Australia’s most cleared state.

“By our calculations, no Victorian government over the past 60 years has a worse record when it comes to park creation than the Andrews government,” says a Victorian National Parks Association report.

By 1992, the Kirner-Cain governments had protected 1.96 million hectares of forest as national park. Between them, subsequent governments protected roughly another half million. Former premier Steve Bracks declared one of his proudest achievements as “the Great Otway Range National Park — the biggest coastal national park in Australia. We removed logging … paying out $80 million and now we’re seeing 10 times more jobs created in tourism, hospitality and recreation in that area.”

Yet despite promises to protect areas including Mirboo North, Strathbogie Ranges, Central Highlands and East Gippsland, the Andrews government hasn’t legislated any large-scale additions to Victoria’s national parks estate. Nor has it implemented most Victorian Environmental Assessment Council (VEAC) recommendations for improved and expanded conservation areas.

Instead, the Victorian government has stewarded the worst ecosystem crisis in the state’s history. Despite its promise to end native logging next year, it continues to introduce logging into state forests scheduled for national parks protection. It subsidised a frequently unlawful pulp log industry that increased bushfire risk, worsened species decline and cost Victorians hundreds of millions that could have funded nature reserves and associated jobs.

In state forests (managed by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action) and national parks (managed by Parks Victoria), limited infrastructure serves a sector of largely white male bush users — 4WD enthusiasts, bikers, hunters and adventurers — over birdwatchers, community walking groups and tourists. The former are high-impact and politically organised; the latter are not. In January, an Upper Yarra management report warned that the “type of visitors attracted are not always aligned with local values considering catchment health and minimising bushfire risk”.

Collection and publication of parks data remain deficient, but one survey ranks “inadequate maintenance of assets or facilities” first in the top 10 threats to visitor experiences. Other non-climate threats include illegal activities, inadequate facilities, visitor conflict, inadequate park servicing, overcrowding, weeds and changes to access.

Some parks host world-class walking tracks, but many are dilapidated or closed, with outdated signs and no information on sovereign Country, First Nations cultural knowledge or ecosystems. “Walking tracks are being managed by feral deer,” one bushwalker told me, nominating Donna Buang, Maroondah catchment, Cement Creek and Tanglefoot loop tracks among those degraded by weeds, logging and neglect.

Alongside impacts on Melbourne’s water quality and supply, this limits Melburnians’ nature exposure. Studies show proximity to nature parks influences people’s willingness to visit them, and polls show 72% to 90% of voters want them protected, expanded and better resourced. According to a 2022 analysis, Parks Victoria receives only “0.37% of the annual state budget, to manage 18% of our land areas and 5% of our marine waters”, with much of this budget going towards metropolitan parks.

So threadbare is Parks Victoria funding that workers warn potential employees on Seek’s review page. “If you can’t deal with lack of funding then this is not the place for you,” one writes. Others write: “Trying to deliver on the smell of an oily rag … So underfunded that it cannot deliver even basic services”; “Understaffed and overworked”; “Maintenance of park assets within a limited budget is very challenging”; “People in regional jobs are feeling disillusioned”.

This might be fixable before the 2026 state election. A well-resourced parks system can relieve the bushfire and invasive weed threats from the bottleneck of crowds, which places stress on rural fringe towns and environments. The Andrews government can reverse the damage from its neglect, protect carbon stocks, create jobs, revitalise regions and improve nature experiences for Victorians.

Great to see Crikey offering news analysis otherwise missing on flagship media.

Dictator Dan isn’t interested in nature except insofar that it can make a profit. He might be a country boy but he seems to see nature only insofar that it has an economic use. He says he is ceasing logging but ‘salvage logging’ is going gangbusters and it could be that logging will continue under this guise.

The Tanglefoot track is itself a VicForests creation after they closed closed the original Tanglefoot Track for ‘rehabilitation’ – read clearfell logging – of beautiful diverse old growth mountain ash forest. I am still angry at that and it happened many years ago. The current Tanglefoot Track was cobbled together using old, probably logging, tracks from the days before clearfelling and given names to create authenticity and it’s not close to Mt Tanglefoot for which the track was originally named.

I walked the ‘new’ Tanglefoot Track the other month, and its a beautiful walk passing a rainforest gully, a heap of big old ash trees as well as some beautiful patches of 1939 regrowth forest. I think you are disparaging the walk quite unfairly, not to mention that the walk crosses the western face of the range of Mt Tanglefoot.

I haven’t been there for a number of years. Walking that track and then the Mt Leonard’s to Mt Monda Track was just too distressing to see with all the mature forest being clearfelled. . The original Tanglefoot Track went the other side of Mt Tanglefoot with a track to the lookout on top. The forest was large mountain ash with an understory of sassafras, blackwood and nothofagus. All dozed and replaced with tree farms right across the range on the side away from the main road.

Using the ‘Dictator Dan’ cachet is not very smart. He was democratically elected by a large majority and current polls indicate the margins are holding equal or better to the last election. If he had of lost the last election, he would have fronted up to the Governor and tendered his resignation – dictators don’t do that! The Dictator title should be left to fringe nutjobs.

However, there is no doubt that the management of forests and parks is well below what is needed. We are facing a severe crisis in deferred public land management costs and that is a terrible situation.

You are right in one sense that we are still a democracy but the Opposition is so weak that the Premier can get away without being accountable in a lot of areas.

He is no more responsible for the state of our forests than previous governments but VicForests has led a charmed life under his government as well. Possibly something to do with the power of the CFMEU as well as his lack of interest in environmental issues.

It’s not the State Government’s fault that the Opposition is such an out of rabble! I grew up in the Hamer Liberal years when it was a generally well run and thoughtful administration until it ran out of ideas. The problem with State forest and park policy is that the State Gov needs Greens votes in the Legislative Council – and if it means the native timber industry is driven out, that is a long way distant from inner city concerns. Meanwhile, we have poorly managed forests and NP’s, and numerous timber towns that will take a huge hit to economic activity jobs in coming months. No one seems bothered by the fact that we’ll just import timber, which even if sustainably harvested still has a heap of transport and emissions costs.

We could have selectively logged those forests as used to happen, and also not turned it mostly into wood chips. There is a source of wood chips and saw logs on the far side of the state, from plantations in SW Victoria and SE South Australia but it is all exported to Japan from Portland. No long-term coherent policy on wood products and plantations.

The problem comes down to Labor trying to square the circle of neoliberal economics in a social-democratic state. It is no surprise the electorate continues to drift to the left, away from both the government and the opposition.

Also any government nowadays doing anything environmental then attracts negative right wing media campaigns, including social media and astroturfing to encourage negative word of mouth about any mooted change, real or imagined….. conservatism precluding precluding conservation or anything environmental….

Over 63 years I have walked and observed the Parks and forests of this state. Over this time I have seen a depressing deterioration of their natural, aesthetic and ecological values. The protection of these were once the primary objectives of PV staff and management. Now, as the article says, they are mainly occupied by cleaning facilities , and bowing to the overriding demands of DEECA and FFMVIC , such as helping with their, mostly destructive, fuel ‘management’ activities. Weeds, feral deer, etc., horses in the high country, are rampant. Climate change looms in the background of all these degrading influences. What once were beautiful walking trails are now either overgrown, or expanded to take in Mountain bikers or 4WDs, while those who simply want to enjoy the beauty and the ambience of the natural world (or practice photography, ecological studies, etc.) are forced into ‘management trails’ or are excluded altogether. It is truly depressing, as one seeks places which still retain a sense of ‘wilderness’ to be increasingly elusive. I can only hope that PV (and all those who care) stand up to this government and convinces it that it’s not all about hard hats, hi-viz jackets and Big Build if we are to have a future worth having.

So true.

As a regular visitor to many of Victoria’s state parks, the last few years have not been kind. Much infrastructure has been neglected, and population pressures are evident in many areas. A clean up of basic facilities such as toilets and tables would be well received rather than outlandish ‘visitor’ centres and hectoring signs.

On a minor note, a claim that ‘white male bush users’ are somehow to blame is crass.

I did think that the “white” and the “male” qualifications with negative connotations implied were irrelevant. If more white males want to bushwalk I would have thought that was a better outcome than not.

Thanks for your feedback lethell and 95dd0a7e2e4104736c7ced8008850769 🙂 I don’t reckon any of the article & linked research is suggesting white males are “somehow to blame”. They just point to the limited infrastructure that favours some groups (demographic largely white men) and wedges these against others. For eg, community groups, tourists and birdwatchers who can’t compete with up to 140 decibel 4WDs driving on potholed middy tracks which are near-impossible to bushwalk on.