Really? The contractors running offshore detention on Nauru and Manus Island were merrily paying millions of dollars in bribes (either by way of inflated services contracts or just straight backhanders)? Who could have predicted that?

The collective shrug of ennui that has met the Nine media group’s roll-out of revelations of systemic and massive corruption infecting Australia’s offshore gulag operation tells us that nobody is remotely surprised. Why would we be?

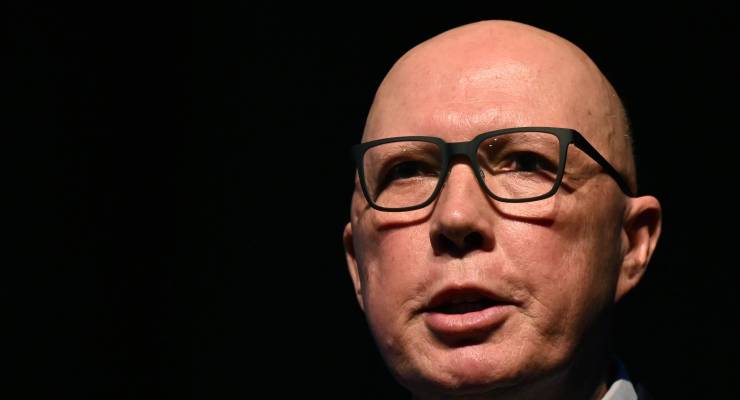

This is taxpayers’ money, funnelled directly into the pockets of foreign politicians as part of the price for being allowed to dump our human refuse on their islands, away from scrutiny and far from care. One contractor was under active Australian Federal Police investigation for alleged bribery when it was handed a lucrative contract by home affairs — after the then-minister now Opposition Leader Peter Dutton had been informed.

It’s a sick joke. Of course it all falls squarely within the scope of inquiry for the new National Anti-Corruption Commission, and if our technically powerful federal laws criminalising foreign bribery are actually enforced, people should be going to jail. It’s a solid enough basis for the Department of Home Affairs to be broken up and a thorough clean-out of the senior ranks who allowed this to happen.

I’m not holding my breath about any of that, but I strongly believe all of it wouldn’t be enough. What is needed here is a royal commission, nothing less.

Groan — another royal commission? I’m sorry but yes; the fact that we have had too many such beasts in circumstances where they weren’t needed or didn’t achieve anything doesn’t detract from their unique usefulness where the context requires.

The positive social purpose of a well-appointed royal commission is twofold: to get to the bottom of what happened (fact-finding) and to root out and address the systemic or cultural causes of dysfunction. When the problems are deep, there is little or no benefit to be gained by exposing only its symptoms.

That is the situation with the offshore processing system. The corruption is egregious and disgusting; the maladministration at home affairs utterly galling. But all of that followed, as night follows day, from something far more fundamental.

The potential for corruption always exists. If a government chooses to do “business” in a foreign country with poor governance and entrenched poverty that risk is extreme. It may be practically impossible to operate without drifting into the grey. This is one reason why there is no surprise in what happened in Nauru and Papua New Guinea.

The problem, it can readily be seen, is not the fact that the Australian government through its contractors fell into the trap of bribery and corruption. The problem is that the checks and balances — the systemic structures of good governance that are meant to prevent such things happening — failed so completely. And stayed in a state of absolute failure for an entire decade. And are still in failure.

It is essential, therefore, that any inquiry into this bucket of shit digs below the surface to find out and understand what went so badly wrong in the executive arm of government; why the whole system failed.

However, even that will not suffice. The ugliest truth is not the corruption of every aspect of proper governance by the Coalition government, not even specifically the black hole that Dutton’s home affairs empire became. In the field of immigration that became border protection, the absence of basic human ethics and decency that has uniformly characterised our approach to refugees and asylum seekers since the John Howard years, could not have been sustained for so long without a solid cultural foundation.

The reality is that the process of dehumanisation of asylum seekers, played out over decades, has inured us as a society to the awfulness that successive governments have felt comfortable perpetrating on our behalf.

To understand how it is that we managed to so lose our way that we ended up using brown paper bags full of cash as a central support of our offshore detention system, and that nobody is surprised now it’s being exposed, we have to acknowledge that that is actually the least of the evils that have occurred.

None of this would or could be explored by a criminal investigation or anti-corruption inquiry. Only a royal commission would have the scope and powers to ask the large, uncomfortable questions, as did the best exemplars of recent history: the royal commissions into institutional child sexual abuse, the banking industry, aged care and robodebt.

Presumably we are not OK, as a society, with the corruption being exposed. I hope we are curious and caring enough to want to know what we did, as a society, that caused our government to so easily fall into it.

Should there be a royal commission into this debacle? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Hear hear! However it might just need a few more prods from the likes of Crikey, Nine and perhaps Four Corners before it will happen

Remember when the Abbott government was caught paying people smugglers to turn around their boats. At the time Tony Abbott told the media (and I paraphrase) “by hook or by crook, we will stop the boats”.

Perhaps he was trying to tell us something more back then and it flew over our heads?

Yes, but ‘failed’ is a feeble and rather passive word for what happened to the checks and balances. They were almost certainly sabotaged by ministers and officials who knew exactly what they were doing. And this behaviour is systemic, not just in offshore processing but in many other areas too. So a Royal Commission is strongly indicated, but it will only happen if the political class that needs investigating chooses to set up that commission, give it an adequate brief, enough resources and sufficient powers. What are the chances?

Yes, so they didn’t fail, rather they worked as intended, as bits of dressing to distract from, yet again, government officials happily breaking the law in pursuit of government repression of human rights, as per Robodebt.

Indeed Robodebt comes after our systems of camps, so it echoes rather than proceeds this trashing of rights and litany of corruption. The history is of accepting that the inhumanity to non-citizens via the camps be later extended to citizens, via Robodebt.

This behaviour is now a feature of the machinery of Australian government, just as tolerating, and even applauding, cruelty and infliction of misery is now a part of our political culture, a bit that generates votes.

There is struggle going on for the corruption of the soul of Australia. Government keeps routinely escaping rule of law and regardless of this the law anyway keeps failing to safeguard citizens and humans generally. Very serious reform is needed, creating laws and institutions with teeth.

And we don’t even need corruption to do it. Albanese today hosed down the eminently sensible proposal from the CFMEU to claw back some of the super-profits that the mining companies make flogging our minerals to be able to pay for some of the social housing we desperately need for homeless and struggling Australians. So poor Australians have now joined asylum seekers and Centrelink recipients as groups to be punched down on so that the powerful can remain in power.

Ex-coppers, (we all might know some) are good at doing crime well, better than the crims. They look up the back of the book and get the answer. Politics is easy, just pay for what you want or need. market prices.., how much for a whole nation or government?

Ex Queensland coppers in particular.

Surely you’re not referring to Prosecuting Sgt (Retired) Peter “Verbals” Dutton?

“Our human refuse” is not ours and is not refuse.

If a royal commission shut it all down, that would be a worthwhile result. Otherwise, like the “Four best exemplars” it would achieve very little except the usual sackcloth and ashes for us all and no punishment for the crims, who in a better world would have their noses and ears cut off as a warning to future politicians.