In 2022, both Macquarie Dictionary and the Australian National Dictionary Centre named teal as their word of the year. Referring to the independent candidates who had great success in the 2022 federal election, the term was everywhere. There was discussion of the teal wave, a teal revolution and an electoral tealslide. While not all of these candidates chose teal as their campaign colour (there was debate as to whether the colour was even teal at all — was it turquoise?) and the platforms of different candidates could be quite varied, the teals offered a distinct alternative to the major parties.

At the Australian National Dictionary Centre, we monitor the language closely for evidence of new words. Our major research project is the Australian National Dictionary: Australian Words and Their Origins. In this dictionary, we record words and senses of words that are uniquely Australian, are used more here than elsewhere, and/or which have special significance to Australia.

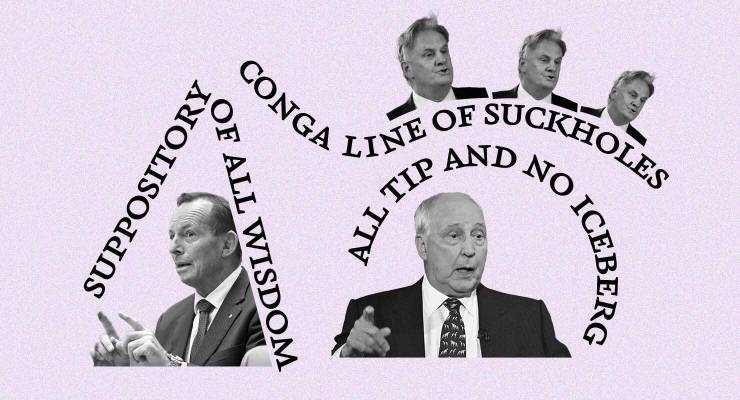

Politics has proven to be a very productive area for new words and expressions, including words and expressions coined by or made prominent by politicians (conga line of suckholes, as Mark Latham quipped), words describing policy (robodebt), and words that relate to our political system (Dorothy Dixer). Some are ephemeral, while others take up a prominent place in our vocabulary.

Politicians are often a gift that keeps on giving for lexicographers. Paul Keating was a great contributor of memorable insults, such as all tip and no iceberg and like being flogged with warm lettuce, although not all of these have stuck around. Tony Abbott memorably made the gaffe suppository of all wisdom, but his figurative use of shirtfront (an aggressive front-on bump to the chest of an opponent in AFL) popularised its use off the football oval. Another oft-cited example of polliespeak is Kevin Rudd’s fair shake of the sauce bottle, a variation of the well-established Australianism a fair suck of the sauce bottle, but no doubt influenced by the expression a fair shake.

It’s fair to say that in terms of recent prime ministers, Scott Morrison made some notable contributions to our language (for better or worse). Although a major contributor on neither the wit nor gaffe front, he gave us a couple of influential political terms: quiet Australian and Canberra bubble. How long these two terms will stick around is unclear. Both speak to a kind of political discourse that has also contributed terms such as the quinoa curtain, goat’s cheese set and latte line. This is a politics of “us” and “them”, notable in recent years, that seeks to attack certain parts of the population (the so-called “woke” elite) and elevate others (the “quiet Australians” whose voices aren’t heard).

Election campaigns are often another source of new words and expressions. Our most recent federal election campaign saw some discussion of Manchurian candidates, loose units and the holding (or not) of buckets and hoses. These are all plausibly ephemeral — although the general use of loose unit seems to be established; the election likely gave it a boost. The election did see much use of two terms that have definitely found a place in the political lexicon in the past decade or so: corflutes (our name for the signs that line the road during an election campaign and transferred from a proprietary name for the material they are made from) and democracy sausages.

Several issues have shaped the broader political discourse of the past few years, including the pandemic and lockdown, and climate change. The COVID-19 pandemic generated, of course, its own language of iso, sanny and covidiots. Most of the words that marked the pandemic have disappeared already. However, the politics lingers. The anti-vaxxer movement has impacted political discourse internationally; our own local contribution to the lexicon is cooker, a term used for someone involved in protests against vaccines, but who is also concerned with a variety of other conspiracies. It’s still in use, but how long the word (and the phenomenon) continues has yet to be determined.

As with COVID, much of the language of climate change is international with few uniquely Australian terms. We most recently took note of the term global boiling, used by the head of the United Nations, António Guterres, which indicated the threat heat poses to humanity. We have seen much discussion of tipping points, renewables and greenwashing. This language will undoubtedly continue to evolve as we grapple with this existential problem.

At a more local level, we have been monitoring the new Labor government for its use of language. So far, the Albanese government has been fairly modest in making new contributions to Australian English. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as it may suggest less of a focus on “gotchas” or PR spin, as well as less weaponising of political rhetoric.

We have taken note of the NACC (National Anti-Corruption Commission), with some appearance of the verb form to be nacced or naccered. And most consequentially this year we have seen discussion of the Voice and the referendum. Undoubtedly, the Australian language of politics will continue to evolve in fascinating and unpredictable ways.

Are there any Australian coinages and language oddities missed here? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

If we count Qantas as politicised being ‘Joyced’ should be included. Basically it means being dudded, tricked, shafted.

And we’re about to be rejoyced, from the look of things.

Paul Keating to John Hewson:

“He’s a shiver looking for a backbone to run down”

It’s ‘knackered’, isn’t it? From horses being sent to the knacker’s yard when they were past it.

Originally, though I gather that it’s being echoed with (..out the same meaning and in) reference to the NACC.

I was so impressed at the time by the little-known Mark Latham’s call of John Howard being “the chief 4rselicker at the head of a conga line of suckholes” in reference to the highly undignified rush to a very dubiously justified war, that I made my own bumper sticker reading MARK LATHAM FOR PM.

I was further encouraged when he almost headbutted The Rodent, but unfortunately it was all a very long way downhill from there…

Come to think of it, that Latham line describes every Australian PM since (but obvz not including) Whitlam, regarding Our Special Friends across the Pacific, and their voracious military-penal-industrial complex. Apparently it’s a competition to see who can turn us into that cesspit the fastest.

“..long way downhill from there..” when he decide to join said ‘conga line’. Very bottom of the barrel now.

What about Gough Whitlam:

Kerr’s cur.

It is the first time the burglar has been appointed as caretaker.

When Sir Winton Turnbull [who represented a large rural seat], a slow and sometimes stumbling speaker, was raving and ranting on the adjournment and shouted: “I am a Country member.” I interjected “I remember.” Sir Winton could not understand why, for the first time in all the years he had been speaking in the House, there was instant and loud applause from both sides.

Whitlam, head and shoulders above the rest, in so many ways.