Tucked away behind the council building in a remote Northern Territory community, Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) officials set up a six-hour voting service last Thursday in the Centrelink office for the Voice to Parliament referendum.

It was one of the AEC’s 193 pop-up polling booths roving around remote NT in the three weeks leading up to the October 14 referendum. The AEC advertised the services as the product of “many, many months” of consultations in person and over the phone with community stakeholders. Its sole aim, AEC NT commissioner Geoff Bloom told Crikey and reporting partner Indigenous Community Television (ICTV), was to ensure remote communities had everything they needed to cast a ballot.

But a three-day Crikey/ICTV reporting trip up the Tanami told a very different story from the AEC’s public narrative. The team visited three communities — Yuendumu (yet to vote), Yuelamu (Mt Allen) and Laramba (Napperby). In short: no-one knew it was coming, and when they arrived no-one knew it was there.

The pop-up polling booths in Laramba and Yuelamu were not pre-advertised (beyond the AEC website), had no day-of advertising, and came with no signs saying “Vote here”. The only visual cue that a vote was under way was courtesy of Yes23 volunteers who had erected a small Yes sandwich board in front of the respective council buildings, strapped a Yes placard to the fence, and parked themselves at the entrance with information sheets on how to vote in favour of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

“I don’t get all the secret squirrel stuff,” roving Community Development Program (CDP) case manager for Laramba and Luritja woman Anne-Marie Walker said. “Why set up in Centrelink out the back? At the very least, put the ballot up on the front lawn.”

Walker found out at 9.15am day-of that the AEC’s 9am-3pm remote voter service was in Laramba to run a referendum vote. She said no contact was made by the AEC prior to — or on — voting day, despite the CDP’s physical position next door to the council building and its reputation as the go-to one-stop shop for anything happening in the community.

Undeterred, Walker took herself over to the council building and suggested to AEC officials that they relocate from inside the back-door Centrelink office to outside the Laramba store if they wanted to catch those few people in community. She explained that many local mob were away on sorry business, off at a sports carnival, or back in town.

The response from the AEC official, witnessed by Crikey and ICTV, was blunt: “I work for Centrelink. I know they’ll come here. They want their mail and they want their money.”

While Crikey and ICTV were talking to Walker, CDP local authority, member of the community safety patrol and Anmatyerre man Ron Hagan turned up. The vote was also news to him. Hagan said he’d seen no signs around community advertising the date and agreed with Walker that the store would have been a better place to set up shop: “Behind the council office is pretty hard for people to see. The shop is better, in the centre. It’s the main one where people come.”

According to the AEC’s original remote voter service schedule, the plan was to put a polling place at the Laramba store on Thursday, September 28. This was confirmed with store owner Cory Kyle two months earlier via a single call from the AEC. He said an official rang to talk locations, but that was the extent of communications: “I said to the fella on the phone, ‘Have it here at the store. This is the heart of the community — you get a lot of foot traffic coming through,’ and he said, ‘Yeah, we’ll do that.’ ”

A spokesperson for the AEC told Crikey and ICTV it speaks to a range of community members before making plans for a remote voter service offering, but once locked in, locations and times don’t change “unless there is a significant event or circumstance”. This is to avoid confusion.

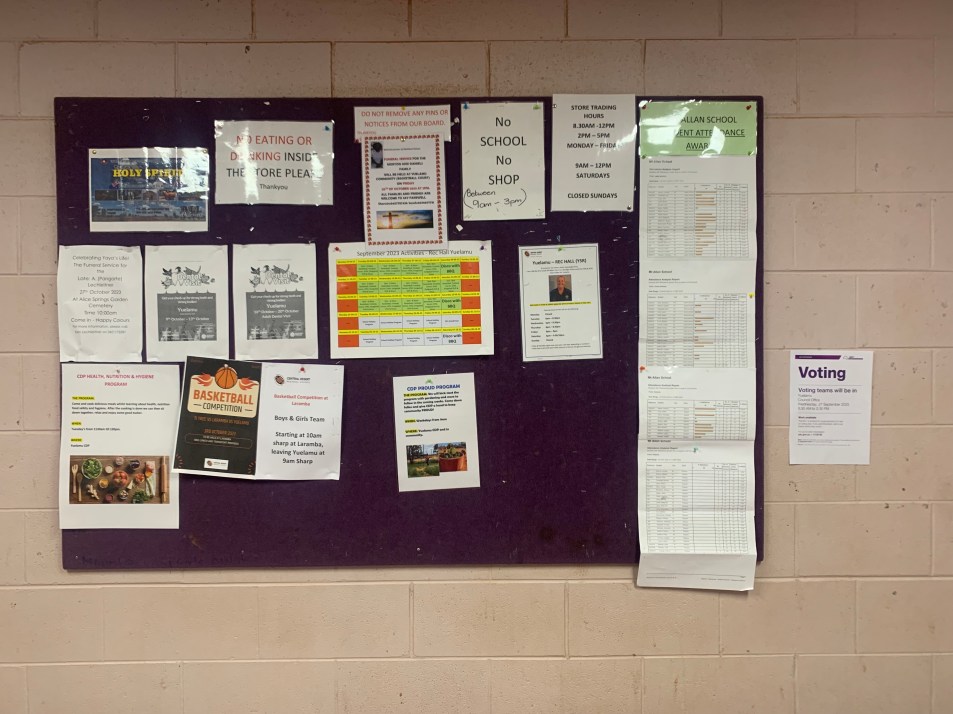

The location change in Laramba was never communicated to Kyle (or others). He also wasn’t told when the AEC would be in community, wasn’t sent any promotional material to pin to the store noticeboard — “I would have put it up immediately” — and didn’t learn that officials were there until he was visited by two at 9.30am asking him to direct community members to the back of the council office. At midday, after a chat with Crikey and ICTV, Kyle found out the AEC’s pop-up poll was referendum-related.

“The community’s been asking about it the past few months: ‘When’s the referendum going to come in?’ I thought it was going to be October,” he said.

Those who did come to vote were given a last-minute word-of-mouth message or rallied by members of the Yes23 campaign who’d planned a presence at every NT remote voter service.

Kaytetye and Anmatyerre woman Valentine Shaw, moving with the Yes camp, told Crikey and ICTV that the lack of heads-up and on-day signs was consistent across all the Anmatyerre communities she’d been to that week. That list included Ti Tree Station and Township, Six Mile and Yuelamu.

At Ti Tree Station, Shaw said only five to six people — “totally clueless” about what was going on — cast a vote: “They didn’t know what we were there for. They thought that we were Centrelink workers.”

She also pointed to the absence of local interpreters outside and inside the polling booth. Shaw had employed her son, Elwyn Daniels, as a language speaker to let community members know there was a vote, to explain the vote, and to assist them to come and cast a vote. That included car pick-ups and drop-offs.

This year the AEC decided not to embed Aboriginal interpreters into remote voter service teams — as it had done in previous years — and instead opted for day-of onboarding of interpreters in community. Bloom told Crikey and ICTV that these on-the-spot hires — formally called “local assistants” — could turn up to the polling booth on the day and say “I’d like to work”. Training would take 15 minutes, there’d be a few “streamlined” forms to fill in (bank details, tax file number — “The sort of information that we will need to be able to pay them,” Bloom said), and then they’d be on the AEC books and ready to work. Their job, once employed, was to deliver AEC messaging in language.

Bloom said these local assistants came with endorsements from community stakeholders that the AEC had done “extensive consultation” with. The assumption was they would “hopefully” be waiting at the polling places for the AEC team to arrive and then hire them, but there was no telling in advance how many local assistants would be employed.

In larger communities where the AEC remote voter service would run for consecutive days, Bloom said it was less pressing if no prospective local assistant was ready and waiting as officials had capacity during polling hours to go out into community, touch base with local organisations, and try to find a bilingual person to assist: “We may not have someone in the beginning, but it doesn’t mean we won’t have someone for the second half of that first day of voting or the next day.”

Stationed at the polling booth in Yuelamu, 280km north-west of Alice Springs, NT Attorney-General and Arrernte and Gurindji man Chansey Japanangka Paech (also working in an official capacity as a scrutineer) said not only had he not seen any local community members recruited as on-the-spot hires, but the absence of Aboriginal interpreters at polling stations was “not good enough”.

“There’s no formal recognition in this entire process about Aboriginal interpreters talking to people and making sure that people have that clarity and that certainty at the time of voting, and that’s incredibly disappointing. The Commonwealth needs to do better,” he said, adding that there were hundreds of highly qualified Aboriginal interpreters across the NT with skills and expertise that warrant more than one day of employment.

Crikey and ICTV found a single A4 sheet of paper with the official AEC stamp taped to the inside alcove of Yuelamu’s Alpirakina Store. Written entirely in English, it included the time and date the AEC would be in community and a call-out for Aboriginal interpreters. It read: “Work available. The AEC is looking for local assistants to help on voting day. If you are interested, talk to our teams when they arrive.”

Yuelamu CDP senior coordinator and team leader Taylor Whitbread said it was unrealistic to expect community members to be there waiting for a job when they had no idea the opportunity existed. The A4 sign, she said, was insufficient.

Whitbread reiterated that it was not well known in community that the vote was happening on Wednesday, September 27, between 8.30am and 2.30pm. She said there’d been chatter that it might be this week or the week after, but nothing had been confirmed.

“I’ve had no phone calls and haven’t seen anyone from the AEC show presence since I’ve been here. And I’m here most of the time,” Whitbread said, adding that she would have happily pinned and posted information at CDP (the go-to notice board for locals) and around community had it been relayed by the AEC, but “there was none of that”.

Like Laramba, the remote voter service in Yuelamu was set up in the council office. Although much more central than the Laramba hide-out (and opposite the local store) it was still without any external AEC signs. A spokesperson for the AEC said this had to do with “transport requirements” including “limited space” in vehicles where the priority was “voting equipment over A-frame or corflute signage”.

In the absence of the AEC’s own branded content, the Yuelamu polling place was again defined by Yes paraphernalia and campaigners out front who tried to catch family as they went in and out of the shop — “Have you mob voted yet? Tell family to come. Tell Uncle David. Come on over, get it over and done with.”

The Yes campaign team — made up of Valentine Shaw, her sister Kaytetye, Arrernte, Warramunga and Warlpiri woman Barbara Shaw and her niece Danae Moore — had shadowed the AEC team across Anmatyerre communities, but in Yuelamu, Barbara Shaw told Crikey and ICTV that officials’ attitudes towards them changed. They were grilled on whether their sign (the same portable sandwich board) had proper authorisation, told they were not allowed to tell people to vote Yes, and were even “growled at” for assisting elderly community members (and family) walk to their cars post-vote.

“We’re the only team out here and we’re showing people how to vote Yes,” Shaw said. “They can’t be judging just because there are no No campaigners.”

Contrary to the position taken by the AEC officials, a spokesperson for the AEC confirmed it had no jurisdiction beyond the mandatory six-meter zone. Out there, “campaigners are free to approach voters and deliver their campaign messages”. The AEC did, however, put out a press release on the purple nature of Yes23 signs, indicating that it could mislead a voter “in proximity to AEC signage” (albeit absent).

In Laramba, the team leader left Yes volunteers alone and instead approached Crikey and ICTV, insisting that any media attendance in community had to be authorised by them: “You need to call the AEC now and let them know you are here. We are running an event.”

This was contrary to advice from the Central Land Council (CLC) that entry in and out of community was permissible (without a CLC permit) pending travel was restricted to public areas accessible by public roads and did not entail an overnight stay. It was, however, recommended to make contact with the community ahead of time.

A spokesperson for the AEC told Crikey and ICTV that it had no authority to admit media into community — that was the jurisdiction of the community itself and relevant land councils: “Media do need to seek permission to enter a polling for a purpose other than to vote.”

In neighbouring Yuendumu, 293km north-west of Alice Springs, PAW Media (representing the Pintubi, Anmatjere and Warlpiri people) remains the go-to community contact. Interim general manager Grace Marshall said it was courtesy of the council that she’d been notified the community was scheduled for a remote voter service on October 5 and 6. She was also forwarded an EOI poster (for PAW to pin up) on how to work the referendum, but that was it — no direct contact from the AEC.

Marshall said the AEC’s so-called community consultation in Yuendumu involved a single AEC official (“piggy-backing” on a Services Australia trip) meeting with a single non-local and non-Indigenous councillor to ask where and when to set up booths and how many booths would be needed.

Despite the lack of consultation with PAW Media, she said the onus still falls on it and other local community organisations “that have nothing to do with the referendum” to put information out in language through radio, social media and paper print-outs.

“We have information on radio that we do ourselves and we’re not funded for, including community service announcements in language to say the polling day for the Voice is the 5th and 6th of October,” Marshall said.

“That’s what PAW is here for. It’s not something we’ve been asked to do.”

This is exactly the sort of article to which I subscribe to Crikey. Good on Julia and Steve. Shame on the AEC, though.

“The response from the AEC official, witnessed by Crikey and ICTV, was blunt: “I work for Centrelink. I know they’ll come here. They want their mail and they want their money.””

Truly remarkable. What does the AEC think it’s doing?

It looks rather like the AEC is inspired by that episode of Yes Minister where Sir Humphrey explains to the hapless minister that it is far easier and more convenient to run a hospital when there are no patients. I thought the AEC was better than this; maybe it’s just a NT thing?

Does not surprise one, during the last federal election many question marks arose offshore about AEC and postal votes they ‘allegedly’ sent to AusPost for mailing offshore.

In many countries those registered, did not receive their postal votes, ever…. not late but appear not to have been sent by AusPost (though AEC snet email stating papers had been sent to AusPost), then AEC personnel did not give straight answers, but worse, selected registered offshore voters received their papers by courier, an option not available to others…..?

AEC can promote itself as neutral and professional, true compared to the mash in the US, but one wonders if their management is influenced by those who don’t like elections and following the voter suppression game observed in the US, UK and less developed democracies?

It goes back much further. There was a inquiry into postal voting at the 2004 Federal Election . I remember putting in a submission about my own experiences as a registered overseas voter.

https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Completed_Inquiries/em/elect04/appendixd

Nope just an NT thing, they are inept and incompetent everywhere.

A perfect demonstration of why a VOICE is needed, not a vote. Just do it!

Totally agree. So sad.

This is appalling. Do we suspect some leaning to one side or the other in this matter?

A gobsmacking demonstration of why the Voice is needed.