China has been using the conflict in Gaza to push its pro-Muslim credentials in its accelerating battle with the United States for influence in the Middle East, underscoring its growing role in global diplomacy as it becomes increasingly outspoken about international conflicts.

It has been one of the most vocal proponents of a ceasefire in Gaza, including at the United Nations, since the beginning of the conflict. And while it has long supported a two-state solution in Palestine, it has been treading a relatively cautious path as it has also developed a strong trading relationship with Israel — most particularly in technology — as part of its “friend to all” strategy.

Yet last month China — together with Russia — vetoed a United Nations Security Council resolution for a ceasefire because it included strong language saying that Israel had the right to defend itself, showing where its sympathies lie.

On November 20, foreign ministers from Muslim countries including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, the Palestinian Authority and Indonesia picked Beijing as the first stop in their tour of permanent members of the United Nations Security Council.

“China is a good friend and brother of Arab and Islamic countries,” China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi said at the meeting. “We have always firmly safeguarded the legitimate rights and interests of Arab (and) Islamic countries and have always firmly supported the just cause of the Palestinian people.”

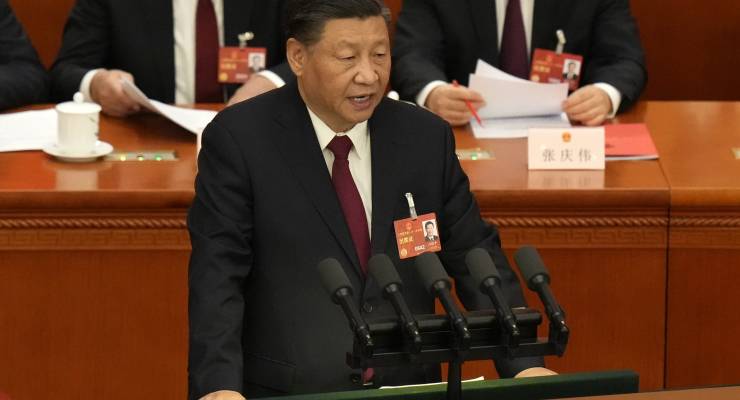

Following this, Chinese leader Xi Jinping continued to try and carve out a role for the Middle Kingdom as a voice of the “global south” at last week’s BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) meeting with the Chinese leadership.

BRICS is one of a range of growing multilateral institutions, including the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, that are being backed by Beijing to challenge the traditional post-war international institutions created and still largely run by the US and Europe. BRICS is set to expand next year to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Iran.

The Middle East has long been important to China as a source of oil and gas. Saudi Arabia was long China’s second biggest crude supplier — having been overtaken this year by Russia — and Iraq, Oman, the UAE and Iran are all in the country’s top 10 suppliers. But in the last decade, since Xi Jinping came to power, China has expanded its trade, investment and diplomacy in the region. The region is becoming a key plank in Xi’s overarching foreign policy program, the Belt and Road Initiative, as it is home to several key international energy and sea trade routes. China has developed a substantial commercial presence in railways, ports and industrial parks that link the Persian Gulf to the Arabian, Red, and Mediterranean seas. It has also increasingly been providing the digital infrastructure to link and wire up nations in the region.

In particular, it has drawn closer to Iran, taking advantage of the country’s fractious relationship with the US, especially during the Trump administration. In March 2021, during the final months of Hassan Rouhani’s presidency, Iran signed a 25-year strategic agreement — focused largely on strengthening economic and security cooperation — with China.

Earlier this year Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi visited Beijing and has described Iran and China as “friends in difficult circumstances”.

It has taken a similar tack with Saudi Arabia, with which it has also been developing close ties since former Chinese president Jiang Zemin became the first Chinese head of state to visit Saudi Arabia in 1999. This was reciprocated in 2006 when Saudi King Abdullah chose China as his choice for his first official visit.

This strategy was rewarded on March 10 this year when representatives of Iran and Saudi Arabia surprised the world by signing an agreement in Beijing in which they pledged to restore diplomatic relations after a seven-year break. The deal marks a fresh turn in Chinese foreign policy, with Beijing moving from its longstanding policy of “non-interference” to “international mediator” and the latest step in the move to a multipolar world.

It has also led to China positioning itself as a potential key player in the Gaza conflict due to Iran’s indirect but heavy involvement and backing of Hamas, as well as Lebanon’s anti-Israel terror group Hezbollah. Tehran says it “stands ready to strengthen communication with China” on resolving the situation in Gaza.

For many nations in the Middle East, and indeed elsewhere, China’s backing of authoritarian and oppressive regimes is as attractive as its deep pockets. As one critic put it: “If anything, the Middle Kingdom’s quasi-colonialism is serving to fortify the repressive governments that dominate the Islamic world.”

Still, Beijing’s efforts to curry favour with Muslim nations stand in stark relief with its ongoing repression of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang province, which only a year ago the UN said could represent crimes against humanity. There have also been recent moves to “rectify” mosques around the country to look less Islamic and more “Chinese”.

But pushback against China for such activities from Muslim nations has been increasingly weak, highlighted by a recent statement from Pakistan last week on behalf of 72 other countries denouncing interference in China’s “internal affairs”.

Put that down to those deep pockets that will underpin even more flexing of China’s growing international muscle in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.