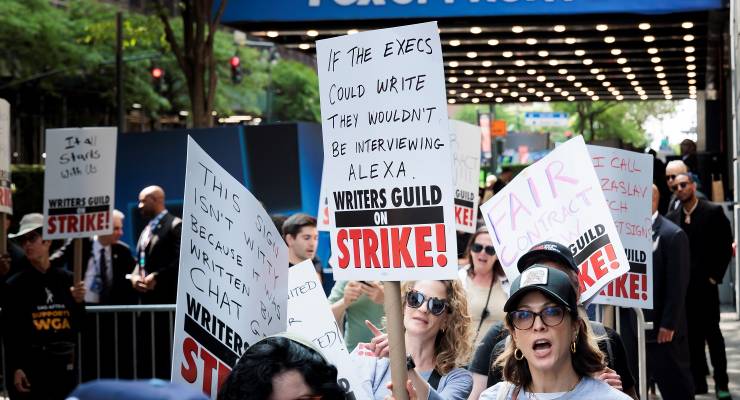

The US screenwriters’ strike, now heading into its fourth week, marks the first concerted push-back by unionised workers against the mechanisation of creativity through artificial intelligence.

It’s a very modern Luddite moment. Like that early-19th-century workers’ protest, it’s a battle by skilled craftspeople to assert the profound humanity of their work in the face of the technology of industrialisation.

The technological determinists of late capitalism — the sort of people who, as David Roth said last month, are employed to find new ways of saying “actually, your boss is right” — shrug with a cynical sneer of inevitability.

But the strikers are asking a more profound question: what’s the value of creative work if there’s no human creativity behind it? To preserve the humanity of their enterprise, the Writers Guild of America is demanding a ban on using AI to write or rewrite literary material or as source material, together with a block on training AI on material prepared by the unionised writers — you know, actual people.

The Hollywood deals are global pace-setters, though success for American writers won’t be the end of AI battles in creative industries. But if the strong US entertainment unions can’t beat the big studios, it’s going to be hard-going for anyone else, particularly in Australia, which is so integrated into Hollywood’s global supply chain of modern media production.

The strike is a symptom of the ongoing disruption of the entertainment industry driven by streaming. The big US studios are responding in the only way they know: cutting costs with cheaper programs and bolstering paywalls with their own streaming products.

It’s come as the collapse of the last large-scale alternative to streaming — cable distribution — is accelerating. Fox and CNN are lurching around in search of an audience, with one sacking an out-of-control host and the other embracing an uncontrollable Trump. CNN has slumped down to Australian Sky’s level of relevance, and Disney has foreshadowed dumping cable for a stand-alone streaming service of its high-profile sports channel ESPN.

The AI ban is just part of the writers’ response. The Guild says writers’ pay has dropped 23% in real terms over the past decade. They want higher rates that reflect the ubiquity of streaming, including a viewership-based residual payment for programs with more viewers (and more transparent data on who is watching what) along with minimum staffing levels to sustain quality and jobs.

The previous writers’ strike in 2007–08 — which extended union contracts to cover work for then-nascent streaming services — lasted 100 days; the one before, in 1988, for 153. This year’s strike could get bigger before it gets smaller. Picket lines are already shutting down productions in the US (Variety has a running tally).

Contracts for the Screen Actors’ Guild (SAG) and the Directors’ Guild expire on June 30. The actors’ union has already started balloting for a strike authorisation if talks break down. That strike would immediately involve SAG members working on US productions in Australia.

Over the past two decades, Australia has tied its film production industry ever more closely to the US. Forty off-shore productions in the past five years have made the Hollywood studios key employers in the local industry. It’s come coupled with foreign ownership of important sectors of the Australian industry, such as Disney’s Moore Park studio, Netflix’s buyout of animation company Animal Logic for more than $700 million, or Paramount Global buying Network Ten as a launch pad for its own streaming service.

And, of course, the Delaware-registered News Corp has a controlling stake in Australia’s own struggling pay-television provider.

The US strike could delay the impact of the 2023 budget’s cultural spend to reimburse the studios with 30% of the money they spend in Australia on big-budget film and television. Replacing the previous Morrison government’s fixed-term Location Incentive, the new continuing Location Offset is estimated to cost about $112 million over four years, in exchange for the studios spending over $400 million. (Never get in the way of studios and a bucket of money; these payments are the cost of doing business if you want a domestic industry.)

Perhaps the strike could fast-forward production of the Australian content quotas that the government’s National Cultural Policy has imposed on the big streamers from next year.

That’s not correct. All of the value, if there is any, of AI generated content is the result of human creativity which has been used to train the AI engines. What is wrong is that no writer has been paid for their work. It has been stolen, and copyright laws have been sidestepped by algorithms that mash the stolen content into rearranged cliches (which are still inferior to new works, but that’s a different discussion).

The writers should ditch this difficult to win strategy of trying to stop the march of technology and instead learn from the masters. In Australia, the monopoly “news” publisher used his political clout to force google and facebook to pay him for news, even though he had no clear legal entitlement.

Writers have a clearer legal entitlement, because the only place the value could have come from is their human minds.

Make the AI tycoons pay for all the content they harvest through ongoing royalties to every author they’ve ever stolen from. That’s a better fight to fight and to win.

It is always a losing strategy to try to uninvent something, whether that wheel thingie or mixing tin & copper.

However, unless H.Sap. is a thorough misnomer, one possible solution is to ensure that the one thing individuals should be able to claim as ‘mine own‘ is the copyright on themselves.

If something appears to be free, then you are the product and that cannot be stopped but the use to which that ‘product’ can be put should therefore require (1) permission (2) a veto & (3) a payment, however minuscule like a Tobin tax because, as we all now, if’n it ain’t got a price, it ain’t worth spit.

On a different tack, it would advisable for people concerned about their future, if any, to refrain from as much of the net/digipokery as possible because, sooner rather than later, it will cease to be in the form currently known & so beloved by all (apparently).

Whether by design, default or disaster knowing how to live in the real world will be be more precious than pearls and a damned sight more useful.

Indeed. Also, perhaps counter-intuitively, one of the primary reasons I post under my real name, and routinely share my material world particulars, including residential address. It’s a prophylactic against having my soul digitised and monetised by the AI master intelligence. Or the Holy Roman Empire, for that matter.

All-powerful overlords can’t disappear you, so long as you hold tight to your unique byline.

The older ones amongst us will remember when overseas records were not played on Australian radio for a long time (due to a dispute) and what happened? A outburst of local talent hit the airways…new bands, new writers and a huge boost to the local industry.

the thing is, that the US has ruled that anything produced by so-called AI cannot be protected by copyright because there is no human creator – so a script generated by “AI” can be used by anyone as the basis of their own movie or series – not great in an industry currently obsessed with IP – however, you can be sure the studios are working on a way to give their “AI” creations the same protection as copyright, but under a different model, like, maybe patents or trademarks

how the studios can save money (and ripoff writers) immediately, is by using “AI” to create existing material and then have real writers rewrite the dreck into something approaching producible – the *trick* here is that, these writers would only be paid based on a SCREENPLAY BY credit because their work is based on existing material (the fact this material is effectively, garbage, doesn’t factor into it) – a SCREENPLAY BY credit amounts to substantially less money than if the writer had created the script from scratch, in which case their pay would be based on a WRITTEN BY credit – these credits also impact on how much writers get paid in residuals

Those are good points, Roberto, that writers can and will use AI as an intermediary source, (which is what Hollywood already does with its layered rewriting process from human origins), and that the pay scale differs for different types of writing vis a vis adaptation.

If quality is any guide or determinant of box office success/failure, then eventually the pay scales will be revised so that the humans who pull the audience — wherever they are in the supply chain — get paid appropriately. Supply and demand will see to that because real talent is always scarce.

With chatgpt so new and surprising it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the seeming accomplishment of synthesising old works. But play with it for a while and you see that the “writing” is cliched and formulaic, no matter how smooth the prose occasionally flows.

AI can make a pastiche of yesterdays hits, but it can’t read the room. Can it innovate? Only in the same way that monkeys can type novels. They can automate the monkeys, but who is going to read a billion random attempts to find one accidental gem?

I remember one of the last episodes of ‘The Twelfth Man’ where all of the cricket commentators are replaced by Billy Birmingham who imitated their voices perfectly….

Tragically, if we can do without you, we might do without you permanently!

But the strikers are asking a more profound question: what’s the value of creative work if there’s no human creativity behind it?

That’s not correct. All of the value, if there is any, of AI generated content is the result of human creativity which has been used to train the AI engines. What is wrong is that no writer has been paid for their work. It has been stolen, and copyright laws have been sidestepped by algorithms that mash the stolen content into rearranged cliches (which are still inferior to new works, but that’s a different discussion).

The writers should ditch this failed strategy of trying to stop the march of technology and instead learn from the master, Murdoch. In Australia, Murdoch used his political clout to force google and facebook to pay him for news, even though he had no clear legal entitlement.

Writers have a clearer legal entitlement, because the only place the value could have come from is their human minds.

Make the AI tycoons pay for all the content they harvest through ongoing royalties to every author they’ve ever stolen from. That’s a better fight to fight and to win.