Earlier this month, Australia’s internet safety chief signalled a seismic change to the way the internet works in this country.

ESafety commissioner Julie Inman Grant rejected the Australian tech industry’s proposed online safety regulations, leaving her office with the task of creating binding and enforceable industry codes for companies such as Google, Apple and Meta.

It is now all but certain that the eSafety commissioner’s version of the industry codes will require these tech providers to scan every message, email and file.

Inman Grant’s justification for the decision was that the industry’s proposed internet rules did not include an obligation to proactively detect illegal online material such as child sexual abuse material (CSAM). However, critics say these efforts also come with privacy and security trade-offs.

Huge rise in ‘horrific’ material

A week before rejecting the industry code, Inman Grant laid the groundwork by announcing dramatic rises in CSAM reports to her office: 8894 reports in the first quarter of the year compared with 3701 the year before. This led to 7927 links to content being identified as CSAM in the first quarter of 2023, a year-on-year increase from 2812.

Inman Grant said the spike was mostly caused by an increase in the distribution and consumption of CSAM.

“While this increase can be partly attributed to more Australians understanding our role as an online safety net, we believe it’s predominantly being driven by increased global demand and supply of this horrific material — a trend we’d contend has been supercharged since the onset of the pandemic,” she said at the time.

An eSafety commissioner-funded study by UNSW Associate Professor Michael Salter and Dr Tim Wong found that tip-line workers and police reported their organisations had seen large increases in online child sexual abuse reports during the pandemic.

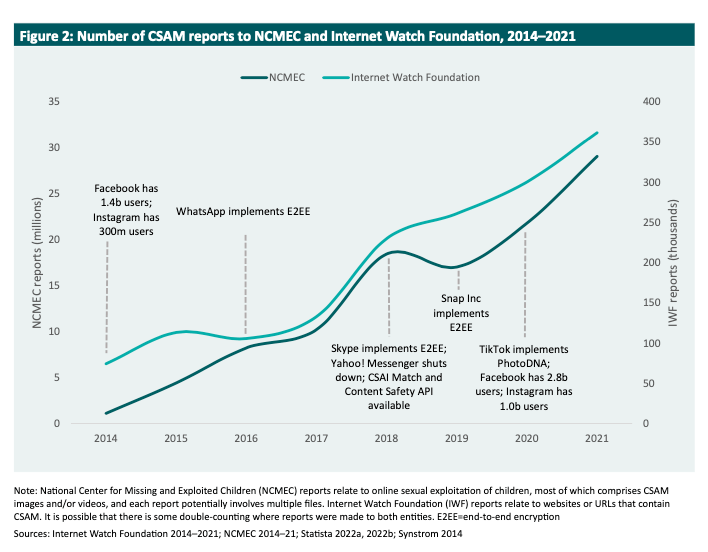

While the pandemic may have supercharged them, CSAM reports have been increasing at an exponential rate for almost a decade. And this increase is generally attributed to abusers who are increasingly connected and taking advantage of new technologies that make it easier than ever before to create and distribute CSAM.

One such technology is end-to-end encrypted messaging services like WhatsApp, which can make it impossible for anyone but the sender and recipient to know what’s in a message. While WhatsApp does take steps to catch CSAM, its efforts are limited to unencrypted information like group descriptions and profile names.

Inman Grant has repeatedly said tech companies are not doing enough to address the growing online child abuse material problem. From the outset of the industry code process, the eSafety commissioner’s office suggested tech providers would be using proactive detection technologies that would detect and flag known CSAM.

A privacy, security trade-off?

Throughout the process, both industry and privacy advocates have argued that mandating these technologies comes with a trade-off. An explanatory memorandum published by groups representing the technology industry noted the measures “could have a negative impact on the privacy and security of end-users of private communications and file storage services”.

Digital Rights Watch Australia concurred, saying it in its submission that an “unreasonable invasion of privacy creates additional security and safety risk for individuals, businesses and governments”.

Spokesperson Samantha Floreani acknowledged that CSAM is a serious issue requiring serious action, but said Digital Rights Watch is concerned the proactive detection measures don’t have safeguards to prevent them from misuse.

“We look forward to seeing how the eSafety Commission proposes balancing issues of privacy, proportionality, transparency and accountability in the standards to come, and engaging with this process,” she said in an email.

A similar debate is under way in the UK, where the country’s Online Safety Bill would also give its online regulator powers to implement proactive scanning. An open letter published in April by tech leaders in the UK, including the head of WhatsApp and the president of Signal, claims that this requirement would undermine encryption.

“Weakening encryption, undermining privacy and introducing the mass surveillance of people’s private communications is not the way forward,” the letter said.

One vocal critic of the measure has been Alec Muffett, an influential UK security researcher, who said politicians were seeking to solve the problem of child abuse using a technological solution.

“Their proposed solution is to put CCTV-like spyware into everyone’s phones, ripe to be repurposed to state surveillance in the near future,” Muffett told Crikey.

Muffett compared a traditional phone wiretap with being able to retrieve a user’s messages. He said phone calls were ephemeral, meaning a wiretap’s intrusion on an individual’s privacy is limited to a time period. Someone’s unencrypted message history, however, is typically available years and potentially even decades after the interaction.

This is why Muffett argues privacy technologies such as end-to-end encryption are justified, and why he condemns technologies that try to circumvent them, such as client-side scanning. He said a myopic focus on tech (including centring discussions around numbers of reports which is not a direct measure of incidents of abuse) ignores a broader discussion about how to address social causes of child abuse.

Referring to his two-year-old daughter, Muffet said: “I want her to grow up in a world where she has robust online privacy, free from state surveillance.”

Passive reporting ‘absurd’

Salter argued to Crikey that the current system of relying on passive reporting — waiting for someone to see and report CSAM, and then waiting for a platform, law enforcement agency or government body to act — is “absurd”, adding that it’s unrealistic to wait for “silver bullet” regulation with no potential drawbacks.

“There’s been a 50% increase in the number of reports of CSAM year-on-year for as long as we’ve kept records,” he said.

According to him, the research is unequivocal: the more available CSAM is, the more people access it. And the harder that it is to access, the fewer people make it.

Salter drew an analogy between online communication and the mail, saying that the reason criminals don’t typically mail illegal objects such as CSAM is because the postal system regulated and monitored: “No one argues that the government has no right to regulate content sent through the mail. I don’t get how they make a special case for online communication.”

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.